Extolled and censured in captivating stories, songs and verse, the tough and formidable Sfakians are an inexhaustible source of fascination. Isolated on the rugged southwestern coast of Crete, they were forced to survive in the barren, unforgiving mountains by their own wiles. From generations of unrelenting struggle they developed an iron will to endure and to resist any threatened intrusion or invasion. They fought fearlessly to repel those who wished to annihilate them, notably the Venetians, the Turks and the Germans, and they frustrated each such invader with a succession of obstacles in a labyrinth of mountain ravines.

Sfakians were viewed as suspicious, superstitious, intractable, incorrigible, defiantly proud and awe inspiring; as sheep thieves, lawbreakers, avengers of blood feuds, believers in vampires, victims of unimaginable treachery, practitioners of marriage by abduction and the creators of a distinctly idiosyncratic idiom, dress and canon of mores. They were hailed for their remarkable beauty, their noble bearing, their pure yet questionable bloodline (they may well have mixed with invading Arab pirates), their superior fighting skills, their commanding stature and their irrefutable courage.

The question of their origin is unresolved. Some historians maintain that they are descended from the Dorian invaders. Others say they are not Dorians at all, but rather people who fled from the Dorians and, hence, people of Minoan stock who kept their ancient ways, the Eteocretans.

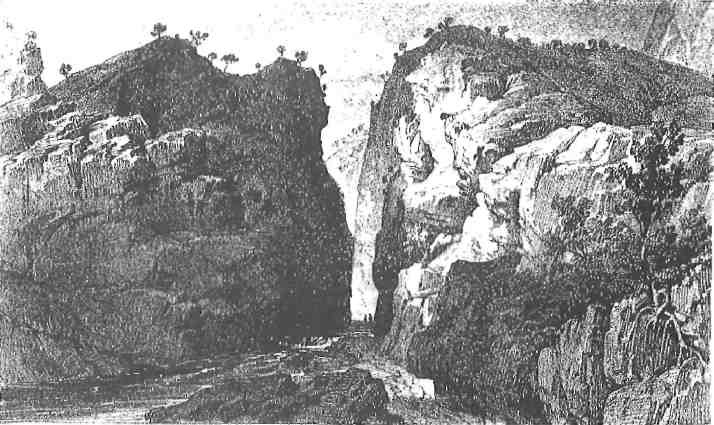

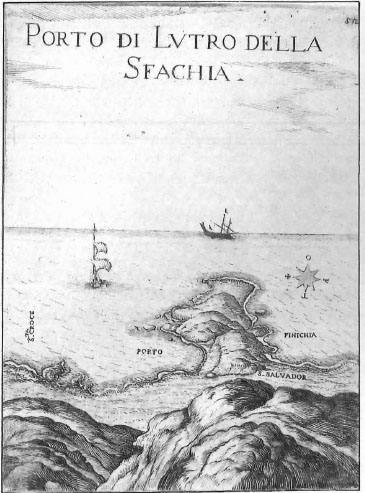

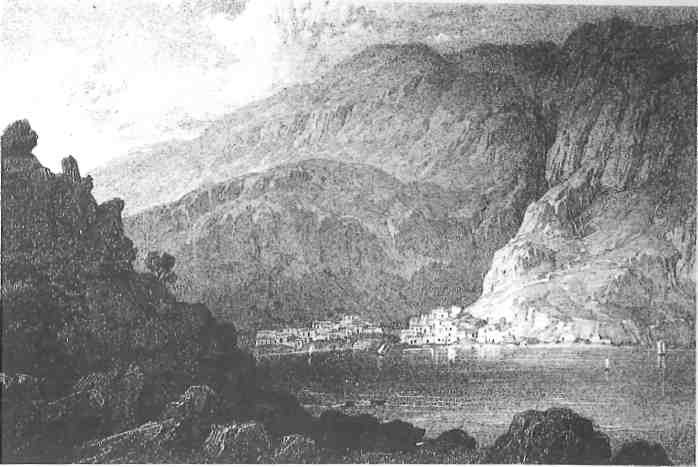

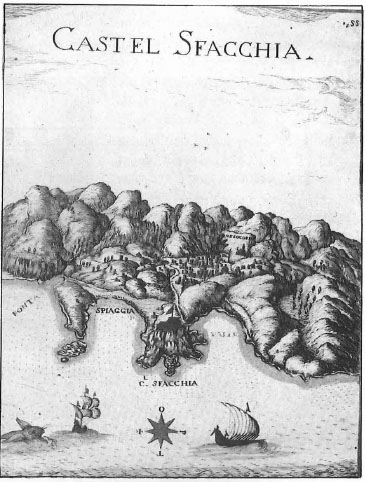

The Sfakians include not only the inhabitants of Hora Sfakion, the chief village of the region, but also the now dwindling population of adjacent villages including Anopolis, Komitades, Ayios Ioannis, Imbros, Loutro and others. Sfakia is actually much less extensive than its vivid history and notoriety would suggest. The area is about 40 kilometres from east to west and 15 kilometres from north to south. Its name derives from an ancient Greek word for ravine and is thus known as the land of ravines, ta sfakia. The maze of these ravines, one indistinguishable from the other, was familiar protection for the Sfakians, and the nemesis of each hostile intruder. In their guarded mountains the Sfakians were more secure than other Cretans. The area is often aptly described as the best natural fortress on the island.

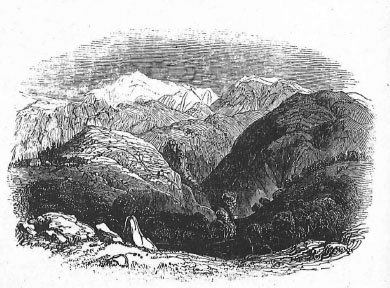

It was not until the 1950s that a proper road was cut through the lofty White Mountains, opening the area up to the modern world. Although the population has diminished and the times are assuredly less turbulent, the mountains remain the same – multiple folds of rock stretching unevenly towards the Libyan Sea. In recent years, with the increased migration of Greeks from village to city and then to foreign lands, the Sfakians have become lesr distinct from other Cretans. But there will always be something tough and uncompromising about Sfakia.

Sfakian severity is well documented. Robert Pashley, an Oxford professor who travelled throughout Crete in 1834, reported the cruel but not uncommon story of a young Sfakian woman suspected of adultery. No charges were ever proven, but her father, a priest, nevertheless invited her relatives to dispense whatever justice they chose. Thirty or 40 vigilantes from Askyfo went to Anopolis where the young woman lived. They took her from her home, tied her to a tree and shot her. More than 30 shells of ammunition tore through her body but she continued to breathe. One vigilante finished the job. The suspected lover was spared. He was reportedly from a ‘powerful’ family. According to Pashley’s hosts, the man was ultimately excommunicated from the church and ended his life by leaping from a cliff.

A Sfakian mountaineer told Pashley that “only a few people ever died a natural death in Sfakia.” When a man was killed because of a blood feud, his family was expected to avenge his death. Decades, might pass before the death was avenged, but the obligation of honorable vengeance remained in force. Succeeding generations inherited the debt, and the honor of the family was at stake. Whenever a Sfakian victim had a large extended family, the murderer had no alternative but to flee. Following his flight his home was burned to the ground and the victim’s relatives took possession of the property.

Present residents of Sfakia can’ recall being unable to visit neighboring villages for fear of death because of ongoing vendettas. Much like the infamous blood feuds of the Mani, the Sfakian feuds were not only imposed on families and inherited by children, but also inflicted upon entire embattled villages. The most notorious village feud was between Gyro and Kampi, equally dividing the loyalties of the town of Anopolis. As recently as 1948, the villages of Lakki and Samaria in the gorge were engaged in bloody encounters with each other. That tragic enmity ended abruptly with the evacuation of the Samaria Gorge when it was declared a national park and game reserve. Within the last 20 or 30 years, persistent feuders have been forcibly removed from Sfakia to distant parts of Crete or surrounding islands.

A myth that has survived for generations dramatizes the stark needs of the Sfakians, and embodies the distrust shown by their fellow Cretans. It is said that when God created Crete, He offered a gift to each place – olives to Selino, vines to Kissamos, wheat to the Mesara, oranges to Hania – until the gifts were depleted and all that remained for Sfakia was barren rock. The Sfakians confronted the Creator and demanded to know how they could live off barren rock. Allegedly He replied, “You’ve got brains, haven’t you? Can’t you see that all these people down on the plains are working to grow splendid products for your benefit?” For some who lived in neighboring villages, these tough mountaineers were a perpetual threat.

The Sfakians had abundant opportunity to develop their brand of stern justice during the lengthy periods of foreign occupation, Crete was invaded successively by the Romans, Arabs, Genoese, Venetians, Turks and Germans. The Venetians held the island from 1212 to 1669. One of the earliest recorded acts of Sfakian defiance dates back to the early 16th century. The events were recorded in rich but horrifying detail by a Venetian chronicler who reported that the Greeks of Sfakia, Selino and surrounding areas banded together and openly defied their Venetian masters. The Greeks resented the powerful and autocratic Venetians and were scornful of their inexorable taxes. The vicious reprisals of the Venetians, however, were unanticipated. Unimaginably savage, they reverberated throughout Sfakia for generations.

Among the defiant Greek leaders in the early 16th century were the Pateropouloi of Sfakia and George Gadhanole, from the village of Krustogherako, who was elected rector of the defiant provinces of Selino, Sfakia and the Rhiza. As rector, Gadhanole was personally able to appoint the officials in his administration and he selected Greeks to fill all the leadership positions. Duties and taxes were then collected by the Greeks and not by Venetians. Unfortunately, this favored Greek autonomy was shortlived.

Venetian vengeance erupted with uncontrolled fury following an innocent visit made by the Greek rector to the home of a Venetian nobleman, Francesco Molini. Gadhanole asked Molini for the hand of his daughter for his son Petros. Gadhanole told Molini that he intended to resign his post as rector and give the position to his son upon marriage. That one visit, viewed by the Venetians as unabashed audacity, triggered a repugnant series of retaliatory acts.

Molini feigned consent, the betrothal took place and the wedding was set for the following week at Molini’s country house. Molini was to be accompanied by a notary and a few friends and Gadhanole and his son were to be joined by a group of Greek celebrants not to exceed 500 men. The Greeks never suspected foul play.

The morning after the betrothal, Molini and the Venetian governor of Hania conspired against the Greeks. Their plan was to conceive a plot so brutal that it “might serve as an example to posterity”. To disguise his duplicity Molini dispatched tailors to make dresses for the wedding party and he sent gifts of fine cloth to his future son-in-law. At the same time, in the city of Hania, the Venetian governor assembled a troop of about 150 horsemen and 1700 foot soldiers.

On the eve of the wedding Molini, along with approximately 50 of his friends, travelled from Hania to his country home in Alikiano where the wedding was to take place. In a seemingly expansive and festive mood, he ordered a grand feast of 1000 roasted sheep and oxen. Gadhanole arrived on the wedding day with about 350 men and 100 women. Molini greeted his guests with the appearance of good will and conviviality.

During and after the wedding the Greeks celebrated passionately. They were plied with wine while the Venetians feigned their own intoxication: the sober Venetians awaited the prear-ranged signal from Hania. Just after sunset the expected loud blast was heard, signaling the departure of the troops that had been assembled by the governor and Molini. By then the dispersed, unsuspecting Greeks were overcome with wine.

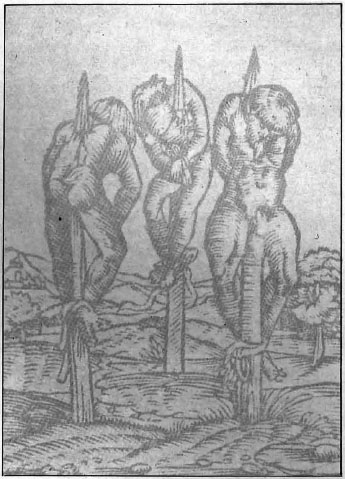

When the Venetian troops arrived they easily bound the sleeping Greeks hand and foot. At dawn Molini and a highly-placed Venetian official, whose pompous title was Public Representative of the. Most Serene Republic, avenged the supposed indignity of the Greeks. Gadhanole, along with his son, the bridegroom, and one of his younger sons were hanged from trees on the estate. Other Greek leaders and their families were shot and also hanged. The remaining Greeks were divided into four groups. The first group was hanged at the gate of Hania; the second at Krustogherako, which was destroyed because it was the birthplace of Gadhanole. The third group was hanged at the castle of Apokorona and the fourth in the mountains between Lakki and Theriso, above Meskla, the village where Gadhanole had lived.

“Thus,” wrote the Venetian chronicler, “they were annihilated and all men who were faithful and devoted to God and their Prince were solaced and consoled.”

Current residents of Meskla claim that a bush called mousklia grew from the tombs of those unfortunate Greeks killed at the wedding, and the corrupted word Meskla became the name of the village.

Atrocities against the Greeks did not end there. The Senate in Venice elected Cavalli as Proveditor and empowered him with full authority to extirpate the Greeks. One midnight he marched with his troops from Hania to the village of Fotigniaco, about four miles away, near Mournies. Seizing everyone from their beds, the Venetians set fire to all buildings in the village, and at dawn hanged 12 Greek bishops. Not yet sated, Cavalli seized the pregnant wives of four of the Greek leaders of the village and, as the chronicler reports, “cutting open their bodies with large knives” tore out each fetus – “an act which truly inspired very great terror throughout the whole district.” Most of the captives were killed. The remaining prisoners were sent away from Crete to adjacent islands. Five or six villagers miraculously escaped that midnight and found safety in the villages of Mournies and Kertomadhes.

Cavalli pitilessly pressed on. He callously ordered all the Greeks of Sfakia, Castelfranco, Apokorona, Selino and Kissamos “to appear in the city, and make their submission”. They all sensed treachery, but the Sfakians alone refused to comply. The Venetians sentenced these defiant Greeks with an insoluble dilemma. After seizing their property, the Venetians placed an unprecedented price on their heads. The only way a Greek could save his own life was by executing with his own hand a blood relative. The Greek was then expected to appear in Hania carrying the bloodied head of his own father, brother, cousin or nephew. Each additional head which was offered would save the forfeited life of another relative.

The incident that reportedly moved the Venetians to abolish the law involved a Greek Orthodox priest. The priest was of the family of Pateroi-Zappa and entered Hania along with his two sons and two of his brothers. They carried five bloodied sacrificial heads. They placed their offerings before Cavalli and the other Venetian leaders and with bitter tears identified each head. Witnesses confirmed their identification. The law was therefore abolished. The grievous spectacle had even aroused the sensibilities of Cavalli.

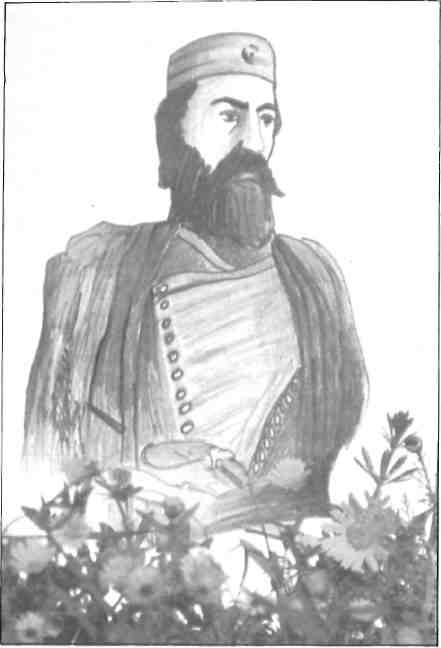

Four centuries of Venetian rule ended in 1669 with the surrender of Candia (now Iraklion) to the Turks after a 21-year seige. The Turkish occupation lasted until 1898. During that time there were some ten Cretan revolts of note but the most renowned was led by the famous Sfakian leader Vlachos Daskaloyiannis in 1770. Daskaloyiannis, meaning “John the Teacher”, was so addressed as a mark of esteem. He was greatly admired by his fellow Cretans. He owned a fleet of ships which traded in the Mediterranean, spoke several languages, wore European clothes and was one of the wealthiest men on the island. During a commercial venture on the Black Sea at the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish war, he met the Russian Count Orloff. Daskaloyiannis became a treasured ally of the Russians and at two inauspicious meetings a strategy was planned. The Cretans agreed to revolt against the Turks at the same time as the Greeks in the Peloponnese. Orloff promised support from the sea: but for that, the Cretans would not have revolted when they did. The Russian fleet entered the Mediterranean in November 1769, the people of the Mani rose in March 1770, and the Russians temporarily captured the port of Navarino. Daskaloyiannis was thereby able to persuade his fellow Cretans that triumph was within their grasp.

On 25 March Daskaloyiannis raised the standard of revolt. The Turks sought refuge within the walls of Hania, and Daskaloyiannis pushed down to the Malaxa ridge with a grossly inadequate force of 800. The plan was to contain the Turks in Hania until the Russian fleet arrived. It never came. Without their promised support, Daskaloyiannis knew the rebellion was doomed and he reluctantly retreated before an army which outnumbered his force by about 30 to one.

The Turks twice called on Daskaloyiannis to surrender. Initially, he thought to, but was dissuaded by his associates, who urged that surrender was shameful. When the Turks again demanded surrender, the Cretans could not refuse. The Aradaina ravine, their last defensive barrier, had been penetrated. A spy had led the Turks to the only path across the defile. The Turks addressed Daskaloyiannis: “…Daskaloyiannis of Sfakia, come and meet me/ And see that you tame birds you drove wild … Trust my letter, whatever they may tell you,/ And so leave Sfakia with men to live in her./ When you come and we talk together,/ All will be settled and we shall be friends.” Daskaloyiannis accepted the Pasha’s invitation and bade a poetic farewell to his fellow Sfakians: “…And you, my friends, my people, brother Sfakians,/ Listen to the advice I give you./ Do not trust the Turk, whatever he orders,/ He will fight with lies to cheat you all./ Avoid the Turk, let no one approach him./ Our fate, our destiny, has not changed yet.” Reluctantly he gave up. He was taken to Iraklion where he was greeted with food, wine and tobacco, then interrogated. He was asked to elucidate the cause of the revolt. “…The cause – you are the cause, you lawless Pashas … That’s why I decided to raise Crete in revolt, / to free her from the claws of the Turk./ First for my fatherland, and second for my faith,/ Third for the Christians who live in Crete./ For even if I am Sfakian, also I am a child of Crete/ And to see the Cretans in torment is pain to me…” He was grilled about the rebels in the Peloponnese. According to the poem, Daskaloyiannis lost control and was then flayed alive in the main square of Iraklion: “…Silence, Pasha, you are wasting your words./ Your net is cast and you will not catch the fish … Do what you like with me, but harm no one else…”

The poem by Pantzelios is quite dramatic and contains precious historical material not found elsewhere. Some critics urge, however, that the poem is not entirely accurate. Several misstatements do appear. Daskaloyiannis languished in prison for a year and was executed in June 1771. In the poem, by contrast, his death takes place on the heels of his defiant outburst to the Pasha. The poem, nevertheless, is of great historical and literary value.

Prior to the Daskaloyiannis revolt, Sfakia had an impressive fleet of about 40 ships. But for that defeat, Sfakia undeniably would have been a more consequential force in the War of Independence and might have enabled Crete to rise in rebellion much earlier.

Turkish rule produced the insidious Cretan ‘Mohammedan’. The Turks converted some of the Cretans to Islam because they were unable to leave an effective military force on the island. These converts became deadly tyrants. The early converts were Venetians or the hybrid Veneto-Cretans who were feudal chiefs and landowners. Their conversion was motivated not by religion, but rather by desires for self-preservation, wealth and power. The converts abused their authority and arbitrarily imposed their will on the Christians, often bullying them with taxes and insults. From the outset of the Turkish occupation, the vokouphiko system was in force in Sfakia. Each household was taxed annually to pay for some designated building or other cause. The taxes from Sfakia supported the poor in the holy cities of Medina and Mecca. In 1672 there was a soubashi, or representative, of the aga living in the town of Hora Sfakion.

The aga or his representative was thereafter rarely absent from the province. Moreover, from 1690, Sfakia was subject to the capitation tax, or haratch, which secured the right to live or the safety of life and limb, and for which each Christian was liable. It was not until after 1760 that Sfakia was relieved of some of these burdens. It was then that the sultan selected Sfakia to protect Fatma Hatoum, granddaughter of Sultan Ahmed III. In other parts of Crete, Turkish rule produced daily indignities for the Greeks. Pashley reports that no Greek was secure in his or her own home. He reported that “any Mohammedan might pass his threshold, and either require from him money, or, what was far commoner, send the husband or father out of the way, on some mere pretext, and himself remain with his wife and daughter.”

He continued: “So atrocious and frequent were such acts of violence and oppression, that I have been assured, by persons well acquainted with Turkey, and certainly favorably disposed to the Turks, that the horrors and atrocities which were almost of daily occurrence in Crete, had hardly a single parallel throughout the whole extent of the Ottoman Empire.”

When Bishop Germanos of Patras raised the standard of revolt at the monastery of Ayia Lavra in Kalavryta in the Peloponnese on 21 March 1821, Crete was unable to join the uprising. Crete suffered from a crippling lack of arms and munitions due in great part to its isolation. The events in Kalavryta, however, sparked a series of reprisals on Crete. The Austrian Consul at Hania wrote: “The bishop of Kissamos has been delivered over to the fury of the people (the Turks), who without regard for his character have dragged him through the town, half naked, by the beard and have cruelly hanged him.” Shortly thereafter, 30 Christians were massacred in Hania. In Iraklion the Metropolitan Archbishop along with five bishops and other priests were executed at the altar of the cathedral where they sought refuge. A major uprising followed with the first revolt occurring in Sfakia in May 1821. Crete revolted from one end to the other.

Sfakian defiance surfaced with renewed ferocity against the Turks. In an account of a Turkish expedition en route to Anopolis, it was told that they had captured a beautiful young Sfakian mother who carried her infant child. She was so remarkably lovely that her captors fought over who would ravish her. While they fought she fled with her infant in her arms, went to a large open well and jumped in. Like many determined Greeks in other areas, she found voluntary death more palatable than Turkish debasement. Some Sfakians chose exile as an escape from further Turkish rule. In a work attributed to Kornaros, the theme of exile is reiterated: “On which road can my loving son be travelling? What sent the light of my eyes into exile?”

A cave below the White Mountains of Sfakia bears a record of Sfakian determination etched in rock: “Here in this cold water cave on the ninth of August 1821 the Pashas Resit and Osman put to death by suffocation 130 men, women, and children of Vaphes, Christians fleeing from a Turkish onslaught after three days of valiant resistance.” Some historians concluded that the Christians of Crete were worse off in 1821 than at any other time in their history.

A dramatic illustration of Sfakian defiance against the Moslems occurred at the outbreak of the revolution when the greatly outnumbered Greeks pursued the Moslems through the gorge to Askyfo. In August 1821 the Pasha was determined to penetrate Sfakia. He assembled an enormous troop of Cretan Moslems and successfully reached Askyfo, and confidently waited for the Sfakians to surrender. Undaunted by the large number of Mohammedan troops, the Sfakians worked tirelessly through that night and the next gathering troops from surrounding mountain villages. They sent word to Malaxa where nearly 100 troops from Askyfo were assembled. By dawn of the second day they had amassed a force of over 400 at Xerokampos, about two miles

west of Askyfo.

As they advanced toward the plain they saw it blanketed with Turkish tents and troops. Their view was partly obscured by the billowing smoke rising from the razed adjacent villages. Roussos, one of the prominent Sfakian leaders, entered his own home on the side of the mountain, a mere musket shot from the enemy. He found a large earthern jar of wine the enemy had missed. He shared the wine with his men, then moved on the plain, opening fire from behind low walls. Other Sfakians joined the attack from just south of Roussos’ troops on the same western slope, from the villages of Petres and Stavrorakhi. These simultaneous assaults infuriated the Moslems. They had seen the Greeks approach but assumed they were coming to surrender: they had underestimated the obstinacy of this resolute and resourceful mountain force.

Just after sunrise and for seven continuous hours, the Mohammedans kept up heavy defensive fire. Despite the quantity and force of the enemy’s ammunition, the Sfakians were favored. From their perch on the mountains, their aim was more precise. By early afternoon, the Sfakians had swelled to a force of 900 and their spirit was buoyed up by their apparent advantage. Small parties of fighters arrived periodically during the battle, relieving tired gunmen. A pivotal cadre of Greeks then occupied the wood above Kares, the northeast corner of the plain. They surprised the Mohammedans, who had already moved in on the village. Exposed to yet another unanticipated attack, the enemy wavered briefly, then quickly retreated. Their flight caused panic among their troops, The Greeks tenaciously pursued the retreating column across the plain and, as the rear guard retreated along the path to Apokorona, the Sfakians continued to unleash their fire. When the enemy reached the descent where the path began to narrow the Greeks sent off a small strategic party. They circled over the northwest hills and surprised the left flank of the enemy at the narrowest part of the gorge – a mere 300 paces from its opening. The Greeks opened fire; the Mohammedans momentarily attempted to hold their ground. The Sfakians, however, were concealed from view and the Mohammedans recognized that their only chance for survival was flight. Many abandoned their horses. The only sure way through the rugged ravines was on foot. They fled to the east, heading for the cover of the mountains.

Before the last of the Mohammedans emerged from the plain, heaps of dead bodies covered the area from the narrow pass to the entrance above Krampi. The dead baked in the burning sun. In 1834, when Pashley travelled through the area, he was shown where these victims had fallen. He observed the evidence 13 years after the event: the bleached bones of ambushed enemy troops.

When the main body of troops got through the narrow pass they found themselves on the open barren mountains above Krampi. The end of the line was still being attacked by a steady pursuit of dogged Sfakians. Many lone Mohammedans attempted to survive in the unknown mountains. The Sfakians continued their pursuit for about 12 miles beyond Askyfo, to Armyro. At Armyro nightfall brought the Mohammedans protective cover.

Although the main battalion was no longer pursued the struggle of the lone straggler had just begun. The wounded simply resigned. With no aid forthcoming they sank down and died. The more able got lost in the labyrinth of ravines or were intercepted by parties of angry Sfakians. For the next few days, according to their own accounts, the Sfakians hunted these stragglers “like so many wild goats”. Some Mohammedans were unable to tolerate the hunger and thirst and ventured into villages begging for mercy and food. Their fate too was unpropitious.

One Sfakian reported that about two or three days after the great flight a Mohammedan arrived at his door, fell to his knees and begged for water. When asked what he did, the Sfakian responded evenly, “I took my tufek and shot him.”

Sfakian tenacity and defiance thus endured through centuries of attempeted subjugation and foreign rule. While its population has rapidly diminished, the determined character of Sfakia’s people and the rugged beauty of the White Mountains endures. The black shirt worn by the old Sfakian men today is a lasting symbol of their renowned resolve. From Venetian times, the Sfakians would not change their style of dress, shave nor eat meat until their revenge was satisfied. Today, the black shirt is a vivid reminder of that rich and valiant past.