In 1988 the Ministry of Culture turned down a proposal for a fish-processing plant in Hania’s historic Venetian harbor; in the early 1990 it rejected another proposal to upgrade harbor facilities in general put forward by Hania port authority and the nomarchy. The ministry, however, had given permission in 1988 for a marina to be built under certain conditions, said the Ministry of Tourism in Athens.

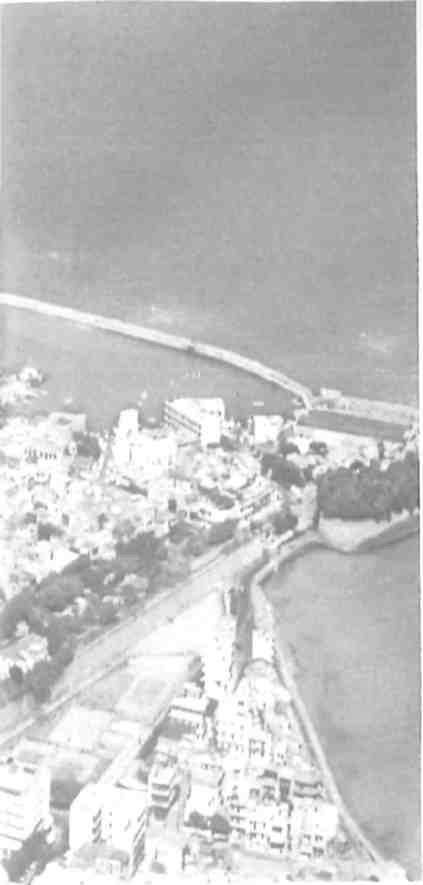

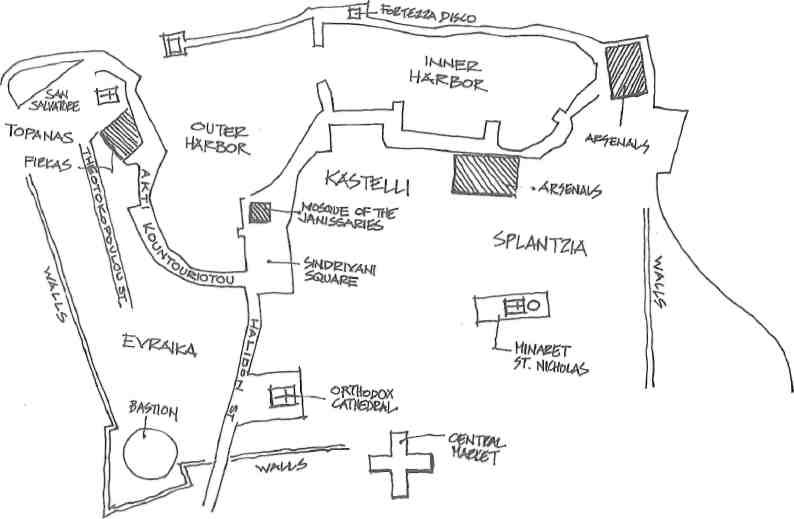

In December 1990, the Minister of Tourism, then loannis Kefaloyiannis, announced a marina for 150 yachts was to be built in Hania harbor, floating wooden docks in both the inner and the outer harbor providing berths. The fishing fleet, he said, would be moved to Souda Bay.

The work was to be funded by the European Community’s Integrated Mediterranean Program (MOP in Greek) aimed at helping developing regions improve their infrastructure. Crete had been the first recipient of such funding when the Program was launched in 1985.

An advertisement calling for tenders was run, according to locals, in the smallest circulation daily of Hania’s five newspapers on December 20. Reportedly, on the same day Alpha ATE, a company experienced in harbor works round Greece and which had built EOT marinas at Zea in Piraeus and Alimos, was awarded the contract. Some have suggested the advertisement was superfluous, not to say a sham, since the contract had been arranged under the previous PASOK administration.

Local opposition to such a marina in the small, historic harbor led to a two-hour, phone-in program on Hania television in March this year. In April, the Ministry of Tourism announced a modified plan. The marina would be confined to the inner, eastern harbor and five floating wooden docks given a trial for five years. The fishing fleet would remain in its traditional place. Repairs would be made to the Turkish light-house standing on the Venetian foundations at the end of the long Venetian-mole.

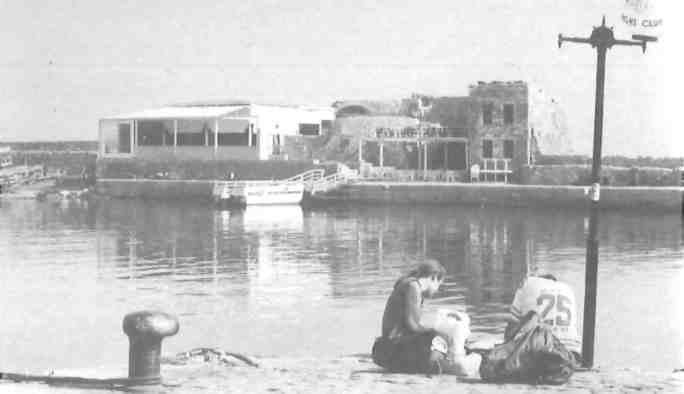

By mid-year, the sign board which stood near the pair of arsenals at the end of the inner harbor, by the old galley-slave quarters, announcing the National Tourism Organization Hania Marina Scheme under Alpha ATE, was lying face down on the rocky shore.

The port authority office was perfectly forthcoming. The marina was being built with original MOP funding of 300 million drachmas (about 1.8 million US dollars at 1990 rates of 165 drachmas to a dollar). The contractors had offered a discount, though, said technical services manager Petros Yiannioudakis, so the work was to be completed with only 200 million. But when harbormaster Manolis Spanoudakis checked figures, he said the sum now available was 330 million drachmas. In Athens, the ministry says the MOP funding, both 70 percent from Brussels and 30 percent from the government, total 350 million drachmas.

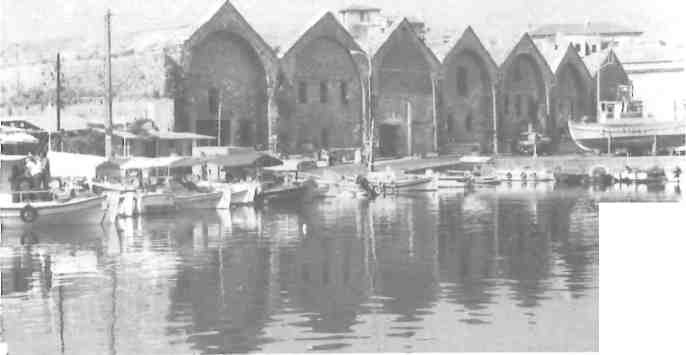

Authorities had bowed to the Opposition and cut the number of yacht berths by about half, to 70 or 80, said Spanoudakis. Fishing boats moored along the quay by the main block of seven Venetian arsenals would move across the narrow inner harbor to floating wooden docks attached to the mole. Hie concrete pier in front of the arsenals was to be lengthened to provide more berths. The wooden docks have already been imported from Norway and last month were being assembled in Suda Bay to be eventually towed around the Akrotiri peninsula to Hania.

Alpha ATE was working under the action of Kleomenis Pasakopoulos, who would have a plan of the project, should anyone wish to see it: the port office did not have one, only a picture of a big Italian marina on its wall. (Th EOT Athens office supplies the accompanying plan).

The company’s main job right now is getting on with urgently needed harbor repairs and reinforcements to the foundations of the lighthouse and mole. “Wave action has eroded the foundations of the lighthouse,” said Spanoudakis. “We have proved it is about to collapse. Mud-jacking (cement injections) is planned to consolidate the foundations with the bedrock. The foundations of the mole are also being strengthened by dumping rocks on the seaward side.”

At the expense of harbor authorities, the whole area was to be dredged and the embryonic breakwater outside the main harbor entrance enlarged with more rocks as a protection against stormy winter seas. The authorities claimed nothing had been spent on harbor maintenance for at least 12 years and that maintenance had been a problem since the Ministry of Culture declared the harbor, along with Old Town, a historic monument in 1964. Previously, four men had been permanently engaged on routine maintenance and repairs in the port.

Warm support for the marina development comes from Manolis Sifoyiannakis who runs the area’s oldest hotel, the Plaza, in Sindrivani Square on the outer, west harbor. Custom from yachties could lift business by 25 percent, he said, judging from the time a squad of Aegean Rally yachts berthed here for a few days. Restaurants, tavernas, bars and tourist goods shops round the harbor benefitted similarly, he said.

A foreign resident in Hania doubts this was typical. “Only real sailors would come to Hania normally, and they don’t spend, except to central market. Those chartering yachts from Piraeus generally go to the Cyclades or the Sporades. The coast of Crete can be treacherous for, strangers and lack of variety in short day-trips is a disincentive. What might be good is a marina at Suda Bay where, at reasonable price, you can take your boat out of the water and store it for the winter.”

Limaniotes (harbor dwellers) are mostly critical of the marina development. Says Dimitris Vrettos, born and bred at the harbor’s oldest restaurant, the Kavouria, “A marina would mean the end of the old harbor. The money would be better spent on doing up Old Town.”

Haralambos Kokkinakis, the last master boatbuilder in business, says: “This is a historic Venetian harbor. It is not right to have a marina here.”

Small-craft fishermen at their kafeneion by the arsenals (neoria) fear they will be sent to Suda Bay. “We live round here and we don’t have cars. We fish out in the Gulf of Hania. In our small boats it would be dangerous sailing round Akrotiri.”

The big swordfishing boats are mostly manned by Egyptians. A general belief seems that they may move to Suda Bay to make way for yachts at their prime site by the arsenals, despite denial of the move by authorities.

Among Hania archaeologists and architects, the marina project is unanimously regarded as outrageous, firstly because it is illegal, so they claim, without permission from the Ministry of Culture, guardian of historic places; secondly because it has not been preceded by any sort of study.

‘The state services’ attempt to put a marina in the harbor is riddled with irregularities,” says Michalis Andrianakis, Ephor of Byzantine Antiquities in Hania until 1990. The most systematic and serious objections to the marina come from Hania’s Architects’ Association. Says Ioannis Tsoukatos, the Association president and head of the Town Hall town planning department: “The undertaking is unauthorized by the Ministry of Culture, therefore it is contrary to the law governing historic places. The harbor is not only ours. It is part of the European Mediterranean heritage, like the Venetian harbor in Valetta and that of the Knights of St John at Rhodes. The Ministry recognized this when it declared the harbor historic and to be protected, along with the town, for future generations.”

“What is more, the work being done is ill-conceived and ill-advised,” said Tsoukatos. “It is true the lighthouse and mole have been undermined by the sea and need repairs. But they need the attention of experts. The work now being done is destructive of what it aims to preserve.”

Rock reinforcements on the seaward side of the mole are blocking underwater gaps left by the Venetians to let water flow in and out. (EOT agrees these are being closed by the Alpha works). A breakwater at the main entrance would further cut down water circulation and leave harbor water stagnant and smelly, claims Tsoukatos.

of Turko-Venetian architectural

detail

“The work is being done without preliminary studies,” he said. This is despite the fact that the Minister of the Environment said in Parliament last December that a ‘definite study’ had been done. This was in answer to a question about the marina from Hania’s four members of Parliament. The minister based his reply on information supplied to him by the Ministry of Tourism.

The port authority admits to feeling beleaguered by the opposition. “We have felt alone,” said Spanoudakis. “Engineers are not regarded as being as sensitive as architects, but we have to do the nitty-gritty work of strengthening a functional facility. We are not out to endanger the environment. We are aiming to improve the harbor for aesthetic enjoyment.”

Spanoudakis describes the opposition as “Lefties calling themselves ecologists. They are vocal activists, a minority. The result is we are not getting the marina we first wanted, only the bare minimum. But we’ll keep fighting and get things done.”

Meanwhile, around and back from the harbor restoration of parts of – Hania’s Venetian-Turkish old town has also been undertaken by the Ministry of Culture through MOP funding. Up to 30 public buildings and historic monuments and 100 private houses were proposed for work under the scheme launched in 1985 with a budget of 750 million drachmas (about 4.7 million US dollars at the 1990 rate.)

By the end of last year, one restoration job was finished, another partially done and about four others begun. Work on six private houses had been undertaken. The sum of 380 million drachmas had been received by the city from the EC, via the Ministry of National Economy. This year a total of 190 million drachmas was expected, 160 million allotted to the Town Hall and 30 million to the Byzantine section of the Ministry of Culture’s Archaeological Service in Hania, responsible for the post-Graeco-Roman to neoclassical heritage.

The fully restored Franciscan monastery church of San Salvatore, near the bastion on the west side of the harbor, at the end of Theotokopoulou Street, is on view. It seems unfair to mention that the two lunettes should be grilled, not glassed, to be authentic. The restoration is finished. The building has a neatly paved square furnished with four blue seats in front. Entry, at least last month, was not possible until the lock was changed since the architect was said to have absconded with the key. (A change of government during the period of the Program’s implementation seems to have led to problems.)

Restoration has begun on the Firkas (the Venetian garrison) by the San Salvatore bastion behind the Naval Museum. More work has yet to be done: scaffolding remains and rusts along the west balcony and the temporary steps up to the flagpole turret seem a fixture.

The precincts throb with life on summer evenings: Cretan folkloric concerts, strobe-lit pop concerts, an official opening of Maritime Week in June and visitors watching the sunset each evening.

Hassan Pasha’s Janissaries’ mosque situated where both arms of the harbor meet, the town’s anomalous landmark, is said to have had work done on its exterior. The Tourist Information Centre based in the building for 20 years or so was relocated so archaeological excavations could be made. The floor was taken up, remains of wall revealed, and the project apparently forgotten about.

Christianity or Islam “

Floor planks lie round higgledy-piggledy. The charred remains of the tourist centre were being removed by municipal workers one morning last June. An unholy, disgusting mess remains in the interior of this prime historic monument unworthy of Christianity or Islam. Byzantine remains in an Instanbul slum may be seen in a more savory condition.

St Nicholas Church in Splantzia, originally the Dominican monastery church dating from the 13th century, has had plaster stripped from a section of the oldest part of an east wall. The priest, Emmanuel Blazakis, has asked about completion of the work several times, he says, though he regards as more urgent repairs to the minaret of the church. It served as the imperial mosque of Sultan Ibrahim from 1645 almost until the last Musulmans left Hania in 1922.

On April 11 this year, a big chunck of masonry tumbled from a fretwork stone balcony of the minaret above the scaffolding which has been supporting the fragile structure for about 20 years. By mid-year nothing was yet in place to stop further falls of crumbling limestone. “It is very dangerous,” says Blazakis. “Children often play around below and the church office is directly underneath.”

Cisterns in Splantzia Square have been made accessible again as in days before the Battle of Crete bombing in 1941, but no lighting or doors were put in, so the place is boarded up, allegedly to stop druggies using it.

The Orthodox cathedral of the Three Martyrs, though dating from 1860, is hardly historic in Haniot annals, but has work proceeding on its bell tower, as its scaffolding shows. Plaster has been stripped off the exterior east wall to expose the natural stone.

Official restoration has been claimed for the bishop’s house attached to Aghii Anargyri, distinguished for remaining an Orthodox place of worship throughout both Venetian Catholic and Turkish Muslim days, but 90 percent of the funding came from private sources says the Scottish Orthodox priest, John Raffan.

No credit has been claimed for the completed restoration of the 19th-century Catholic church in Halidon St, run by Capuchins in a courtyard of the old Franciscan monastery. An Italian architect supervised the work, funded for a sum said to be 30 million drachmas (160,000 US dollars). Roof retiling is also nearly finished. A re-dedication service in June was attended by the head of the Catholic Church in Greece, the bishop from Syros (who helped local Filippino girls scrub the floor for the occasion).

Other public buildings listed for attention include some of the arsenals, where Venetians employed many specialized craftsmen for centuries constructing and repairing their galleys. Despite war, plague and recurring commercial crises, Venice maintained a constant number of craftsmen, most Venetian.

The sizable and largely derelict ruins of the convent of Santa Maria del Miracoli in Kastelli are also mentioned as up for restoration. The habitable part, a Turkish house straddling arcaded cloisters, was bought for 1000 drachmas in 1924 by the father of the present owner. The family run a hotel in the premises, unaware of designs on their property.

The plan to restore private houses has barely begun. A committee including elected neighborhood members has selected 100 old houses in the Topanas, Evraiki (former ghetto), Splantzia and Kastelli districts within the Venetian walls. But only 35 owners have been able to meet the criteria required for restoration.

Permits from the Archaeological Service and Town Hall had to be procured and paid for. So was proof of ownership and permission for work from all landlords, a difficulty for some with family members scattered around the world. Financial standing, with tax department documentation, also had to satisfy authorities.

Work on six of these 35 houses began, in random order. The original committee was then disbanded and a new committee formed in 1990 to reconsider the list. Last September the Ministry of Culture set up another committee, including the Ephor of Byzantine antiquities in Irakleion, Manolis Bouboudakis, archaeologists and architects to oversee the scheme.

The initial five-year restoration plan took cognizance of the conservation, development and restoration plan drawn up in 1977 by Kalligas and Romanos, an Athenian town planning office. This had supplemented an earlier study by other Athenian town planners, Doxiadis Associates, drawn up in 1964 when Old Town was initially declared a historic monument, at the same time that the Ministry of Culture was first established.

Official ministry policy in the 1960s and 1970s was to breathe new life into historic monuments, hence sprang up the concrete and glass Xenia Hotel at San Salvatore bastion like another Xenia under the Palamides fortress at Nauplia. Such out-of-character development in historic places sometimes occurred for other reasons: multistorey hotels in Hania like the Porto Veneziano on the inner harbor and the Loukia on the outer one went up under ‘special dispensation’ during the years of the dictatorship.

Michalis Andrianakis believes professionals with clear ideas are needed to implement such a restoration scheme. ‘They must work with ideas and not haggle over them. They should put self-interest aside, since preserving Old Town is a matter of preserving our cultural heritage,” he says.

In his view, the Ministry of Culture has not continued to play its part. “I don’t know why: it is not a political matter. While Melina Mercouri, as minister of Culture, helped very much, Mitsotakis cannot be proud of Hania now.”

The matter is out of Andrianakis’ hands. Though transferred to a position in the Cyclades Archaeological Service, he spends time at home here researching aspects of the medieval and Byzantine art history of Hania, of which he is an acknowledged authority.

Andrianakis says he has twice won court cases in Athens for wrongful dismissal, but he has not been reinstated. It is suggested he has supporters who have let the Hania Byzantine office run down to show how indispensable he is. Boudoudakis exercises the authority of Ephor in Western Crete from Irakleion, but was engaged in the Mesara at excavation of a newly discovered basilica said to have seven naves – therefore inaccessible to this reporter.

Andrianakis was removed from Hania because he used his power as Ephor to put his foot down and say no, according to a short-term resident ‘foreigner’. Another points out his mistakes. Under his direction, plaster was stripped off old Venetian stonework, then replastered using wrong material (vintage lime, not freshly slaked, to stop flaking), spread thinly (to let the stone breathe), not slathered thickly.

He authorized the rebuilding of a section of Venetian wall or rampart next to the central market, hardly a priority with a tottering 17th-century minaret threatening Christian heads.

Andrianakis also invited ridicule by allegedly banning whitewash and ordering the old town to be painted cream, ochre and pink, with chocolate-brown woodwork. The pinkening of Hania is easily seen. Blushing fagades peek up the vistas of narrow streets. The domes of the harbor mosque still show their odd rosy cheeks in some lights.

A few pashas’ bones may be creaking down under the smart paving over their graveyard. Some of these 17th-century notables might have remembered Sinan’s Instanbul in its youth with his 80 pale domes (wasn’t it?) and mosques undulled by wood smoke. No such Ottoman architectural genius practised in this Western outpost of empire. Turks generally mimicked Venetians in Hania. An expert’s eye is needed to pick an authentic Venetian from a Turkish imitation door.

In the difficult position of trying to run Hania’s Byzantine Archaeological Service is Haniot architect Toula McGann who, till last May, commuted weekly for seven years to work in the Irakleion office, because of ‘problematic’ working conditions she experienced in her hometown office.

The implementing of the Old Town MOP plan in Hania was hindered because the Ministry of Culture could not provide its mandatory 30 percent of the funding regularly, she claims.

Another impeding factor is workload. Since Old Town was tagged historic, permission has been required for structural changes to buildings. Final application in the present regime, with signatory power only in Irakleion, means a month’s delay for (at least legal) alterations.

Out-of-character features, however, may be observed, some conspicuous, like the Fortezza Disco on the Venetian mole, said to have been authorized by Melina Mercouri when she was minister of Culture, although she might not recognize today what she approved. Reconstruction overshadows the remains of the fortress chapel of St Nicholas and a cheapjack plywood adjoining structure is painted blue. Criticism of its looks, however, is secondary for those overwhelmed by its fortissimo sound till the small hours. Court proceedings have been initiated by harbor hotels and sleepless residents, led by the Hotel Porto Veneziano. Delays regarded as deliberately obstructive were being experienced in getting a court hearing in June.

Hania’s restoration, preservation and general development may thus be attacked from various fronts. A purist berates a popular restoration style, known as ‘naif, rustic kitsch, ill-suited to Venetian architecture. A visiting German wonders at apparent ignorance of contemporary restoration skills.

Choice of public buildings for MOP funding is questioned: why cannot the Orthodox church maintain its cathedral when the Catholic church does its premises over the road? (a silly question if one considers it financially rather than theologically).

Work methods are definitely slack: scaffolding is allowed to rust, stripped stonework to crumble, keys are lost, doors ill-fitted, flooring left torn up.

With 70 percent of funding coming from the EC, accountability of some sort ought to be demanded. Problems in implementation would seem unlikely to be solved by getting rid of local professionals. But abusing the public sector for purposes of political patronage must lead to ideological compounding professional differences of opinion to the point where stalemate may be reached.

Perhaps the EC should rethink MOP. Pumping money indiscriminately into underdeveloped regions like Crete – one of the remotest and hardest to integrate parts of the Community – is likely to lead to waste. Locally-funding by ANEK shipping line may be seen as the chief instrument of Hania-area development in the last 20 years. Human resources mean fully as much as monetary ones.

If the EC wants to fund preservation of what is left of this late medieval and Renaissance Venetian island jewel, it might consider funding Haniot professionals to study restoration schemes abroad. Send them with backpacks and go off to, for instance, Jerusalem, Warsaw and Prague. Do they want Hania rebuilt like bombed Warsaw was, restored to the nth degree like the Jewish quarter of Jerusalem, or preserved like its contemporary, Prague?

Hania’s problems are far from unique. Brussels might pick a dozen restoration schemes and have Cretans study and report to Greco on them before giving them other people’s money. To let botched work continue on Hania’s – unique but for neighboring Rethymnon’s – evocative blend of Venetian and Turkish architecture is a pitiable reflection on EC policy: a single trading and monetary region will surely be dust and ashes without brotherly cultural sharing.