The most remote of Greek islands, Kastellorizo lies just opposite the south coast of Asia Minor and the Turkish town of Kas. The island may be a speck on the map with only 130 inhabitants, yet it is anything but the sleepy, provincial, neglected outpost that most guidebooks say it is.

We went for three days, but found it such a surprisingly vital, beautiful, even rambunctious place that we stayed a month, loving everything on what is locally known as the ‘Rock’.

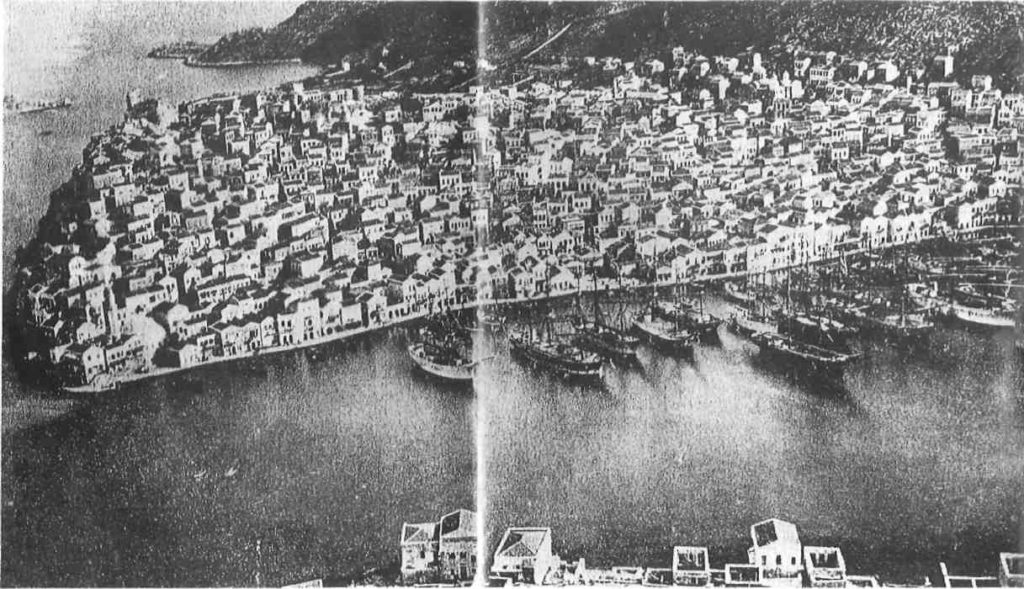

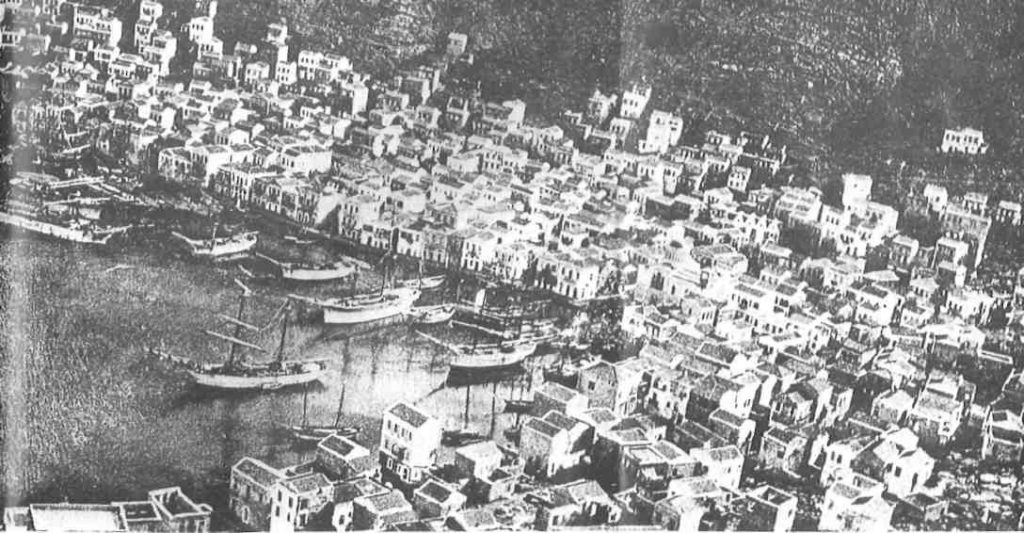

The island’s only town is studded with greenery and there is one tiny farming area in the hills above it, but for the most part Kastellorizo is brown, bare stone with not a tree in sight. Yet the island was once a rich and bustling center of commerce, with as many as 15,000 inhabitants enjoying a grand style of life. Kastellorizan houses were built on a big scale, two-and three-storey mansions that contained large rooms, fine woodwork, luxurious furniture, and artifacts gathered from the far corners of the Mediterranean.

Known as Megisti in those days – it was the Italians during their occupation of the island who gave it its modern name, which translates as Red Castle -the island had numerous churches and monasteries, many excellent schools and active fraternal organizations. The islanders’ affluence was based on their holdings on the mainland. Until the exchange of population in 1922 the entire Lycian coast was inhabited by Greeks. They criss-crossed between the mainland and the island in their sail-boats and fishing craft, doing a vast business in citrus fruit, vegetables, seafood and sponges.

Not only were the Kastellorizans successful sailors and traders, but they were learned, even a cultured bunch, who saw to it that their children became educated. This earned them the reputation of being ‘The Jews of the Aegean’.

Kastellorizo was also strategically situated for international trade and shipping. Even today the port displays a large sign reading “Welcome to Kastellorizo – Europe Begins Here.” In former days, Dorians called here, followed by Romans, Byzantine Greeks, pirates from Asia Minor and Africa, and the Knights of St John, who built the still-imposing and formidable fort which has provided the locals with sanctuary innumerable times down through its turbulent history.

The island’s deep, U-shaped harbor also attracted brigands and warlords over the centuries, and it even served· as a landing place during the 1920s and 30s for Air France which used Kastellorizo as a refuelling center for its sea-planes bound for Asia Minor and Africa. When steam replaced sail, several European shipping companies made Kastellorizo a main stopping-off point.

Kastellorizo lost all strategic and economic importance by Ataturk’s defeat of the Greek army and the subsequent expulsion of all Greeks from the Turkish mainland in the mid-1920s. Another factor in the precipitous decline of the island’s fortunes was when it was politically detached from the mainland and ceded to Italy in 1920.

That was the beginning of the Kastellorizan diaspora. Most of them headed to Perth, Australia, where some 10,000 people of Kastellorizan descent – they call themselves ‘Kassies’ – live today. These Kassies are a tight-knit group that publishes its own newspaper, maintains old folks’ homes and funeral parlors, and sends hundreds of visitors back to the island each summer. Their attachment to Kastellorizo is deep and profound. Many have poured money into the island to help improve its infrastructure or to rebuild family houses.

Since most of Kastellorizo’s port town was destroyed by bombardment during World War II, many intact houses were taken over by squatters. Now, with land values on the rise, the original owners and the squatters (who have legal rights to property after 25 years) are at each other’s throats.

The squabbles are further complicated by the lack of water. There are some cisterns, but most of the water is shipped in by tanker from Rhodes. The Kastellorizans fight over it, though tempers should cooled down when construction of a huge desalinization plant (paid for by the Greek government and the EC) is completed in a few years’ time.

A smaller one, largely financed by the Kazzies and built after the war, has been poorly maintained, producing only a trickle of potable water. Even though Kassies complain that the locals have wasted – or even skimmed off- their money, they Seem fanatically devoted to the island. They revisit their patrida every summer, in ever-increasing numbers. Many are second- or even third-generation and arrive with a piece of paper in their hands showing where the old family house is supposed to be. Their consternation can be imagined when they find that the house has been long occupied by squatters. Off to Rhodes the Kassies rush, to find a lawyer to represent them in court and try and win back their property.

Today, Kastellorizo is still something of a ghost town and badly needs a cleaning up. The main life is concen-trated on the waterfront. The island’s one hotel, the Megisti, sits at one end of the port; the opposite side is dominated by the castle and some official buildings. One houses Kastellorizo’s small but fascinating museum. In between are a smattering of houses and pensions, a covered market, a few shops, several bars and tavernas where everyone gathers at night to eat, drink and gossip.

Small as it is, Kastellorizo with its 130 permanent residents seethes with activity, vitality and conflict. Life was so tough after World War II – physical devastation and isolation, scarcity of water and food, and a lack of jobs were just a few of their problems -that the Greek government actually paid each resident a stipend to stay in place. Even today, when yachting and tourism are beginning to bring prosperity, Kastellorizans are not required to pay taxes. There is not a single cash register on the island and the police and customs officials have a distinctly laissez-faire attitude when it comes to local dealings with Turkey (just a 10-minute trip away by speedboat). Food, liquor, boats and visitors flow in and out freely, and the island even serves as the first stopping-off point for a pipeline of Kurdish refugees, most of whom end up in a refugee camp outside Athens.

The local population is split between two power blocs or clans, both of which are headed by strong, squat, big-voiced women. All communities have their internecine conflicts, but Kastellorizo is rare in that its battles are tin ashed out in public, at peak volume, at just about any time of the day or night.

Some of the infighting is over trivial matters – “you opened your taverna after-hours, while mine was closed”- but most of it has to do with more urgent issues such as land and water:

Apart from the residents and the Kassies, the third group of people found on Kastellorizo in summer are the ‘yachties’ – those who arrive on private or charter boats from Turkey, Greece, Cyprus and Israel. The ‘yachties’ leave lots of money on the island, mostly in its restaurants, shops and bars, though some of the locals also cash in by taking them by rubber boat to visit Kastellorizo’s ‘Blue Grotto’, a high-vaulted seaside cave as large and beautiful as Capri’s. Seals have nested in here, on rock shelves that drop off steeply into a 100-meter-deep azure pool.

The fourth segment of summer visitors is comprised of a handful of adventurous backpackers and Grecophiles, some of whom join the Kassies in the 50-bed Megisti Hotel, others of who doff down in a pension, or sleep somewhere on the rocky coastline. Many of these visitors turned out to be from Italy, drawn to the island by the way it was idyllically rendered in the Oscar-winning Italian movie, Mediterraneo, which deals with the wartime love affair between an Italian navy commander and a Greek woman.

Life is simple and refreshing on Kastellorizo. It may be scruffy and a bit crazy, but it is no fake Greek island, like Mykonos or Paros. It is as real, as challenging and pungent and vibrant as a society can be. Though the island has no beaches, one can find wonderful swimming spots and clean blue water just a few minutes’ walk from the port, especially on its Mandraki side. There are splendid hikes to be taken to one or another of the numerous old monaster-ies and churches to be found in the hills above the town, and it is possible to hire a small boat to take you to a nearby islet for a day of swimming, diving and picnicking.

It was on one of these called Ro, where an old woman, a shepherdess, came in for a measure of fame. She had been hired by the government to keep the Greek flag flying over that rocky islet where sheep and goats grazed. When a couple of Turkish journalists sailed over and as a prank pulled the Greek flag down and raised the Turkish, the shepherdess sprang into action. She hauled down the Turkish colors and ran up the blue-and-white again. She was only doing her job, but mythology took over and transformed her into a kind of Joan of Arc, standing up patriotically in the face of the adversary.

The Woman of Ro died some ten years ago, but is remembered on Kastellorizo with a statue and plaque. This past summer, the Greek government decided to honor her further on Veteran’s Day by sponsoring a concert-under-the-stars featuring the noted singer Nana Mouschouri. The concert was heavily promoted both in Greece and abroad. Boats and extra planes were laid on to carry hundreds of visitors to the island. Free food and drink were offered. It was surely the biggest thing to happen on the island since World War II.

A coordinating committee drawn from the navy, army and air force arrived on destroyers and helicopters to handle the logistics. Greek TV sent a crew to set up and tape the event for Eurovision. Everyone was abuzz with excitement and anticipation – everyone except the Kastellorizans themselves.

True to their reputation as the most disputatious and cranky Greek islanders, they tried to argue the military out of their plans, pointing to the lack of water, facilities and silverware. Kastellorizans interviewed on TV wondered why all this money was being spent on a concert, when it should have been used to repair houses or speed up work on the desalinization plant.

In the end, the concert went off as planned. Nana Mouschouri arrived by warship, accompanied by Manos Hadzidakis and his full orchestra. In the face of a strong meltemi, she sang her heart out, backed up by the passionate playing of Hadzidakis, and in the audience were hundreds of young and old folk from Rhodes, Kos, Symi and even the mainland. But hardly any Kastellorizans were there, protesting the concert by their absence.

The unlikeliest surprise we encountered was the discovery that Kastellorizo’s daily bread was being baked by two Vietnamese brothers, Pham Van Voi and Pham Van Vinh, aged 38 and 20, respectively.

Vietnamese bakers on a Greek island!

Naturally, we wanted to know how they had got there. We learned the story in the course of an interview, in a mixture of Greek and English, that ranged over a week-long period. It was a story that contained all the elements of great drama – courage, terror, desperation, compassion, struggle, love, defeat and triumph.

Pham Van Voi was born and raised in Can-Tho and joined the Vietnamese army in 1973, seeing action for the next two years. When the Americans left the country and it fell to the communists, Pham Van Voi spent four months in prison before being released. He returned to work as a farmer and fisherman, and begun smuggling people out of the country on his boat in the early 1980s.

In July, 1984, he himself decided to leave the country for good, taking his brother with him, accompanied by 37 other adults and children. Several other boatloads of people sailed with him for Singapore, all of which were lost when a typhoon came up in the middle of the China Sea.

Days by went during which many freighters passed by but never stopped. Finally, when everyone had reached the limit of endurance, a ship slowed, circled them, and finally decided to take them aboard.

The freighter was the Olympic Splendor, owned by Onassis. Pham Van Voi remembers the skipper only as “Captain Dimitri”, but recalls that he treated all the boat people with utmost kindness. “He not only gave us warm clothing, food and medicine but gave each of us 200 dollars out of his own pocket.” The Olympic Splendor took them to Singapore, where the local government sent them to a refugee camp. Again, they were treated with kindness and courtesy.

As part of a United Nations program, the Vietnamese boat people were allowed to select which European country they wanted to resettle in. Because they had been saved by a Greek freighter and had such warm feelings for Captain Dimitri, most of them chose Greece. The Greek government sent a teacher to the refugee camp to give language and cultural instruction.

Once they reached Greece, the boat people were housed and fed by the Greek government, which also helped everyone to find jobs. Pham Van Voi went to work’ in a commercial dry cleaning plant, working two shifts a day to save money and help his family back in Vietnam. He and the other Vietnamese in Greece chipped enough money to buy Captain Dimitri a motorcycle.

After a year, he decided to become a carpenter and found a master craftsman who agreed to take him on as an apprentice. His employer liked his work so much that he offered to send him to a building site of his on Rhodes. Pham Van Voi went there with his brother in tow. There, he was baptized in the Greek Orthodox faith and given the name Efthymios meaning ‘good spirit’ and married Josephine Argente, who had come from the Philippines to work as a domestic.

After two years, Pham and his family came to Kastellorizo on a construction job. They loved the island so much that when the job ended abruptly owing to a lack of funds, they asked to stay on if jobs could be found for them. The mayor arranged for him and his brother to work in the local bakery, and for Josephine to become a cook and waitress in a waterfront restaurant.

“The baker taught us how to make bread, but he was a bit crazy. Failing to pay his flour bills, he had to flee the island. That left everyone without bread, so the mayor once again stepped in and asked me and my brother to take over the bakery ourselves. In return, we were given a free house to live in during the tourist season, when it is not possible to rent an ordinary house,” said Pham.

So for the past year and a half, the two Vietnamese brothers have been baking all the bread for Kastellorizo. It has not been an easy task. “The ovens are so old and bad that it takes four and five hours to make bread, double the time it should. Also, since the island’s population swells to five times its normal size during the summer months, we need to make a lot of bread. Besides, all the flour and other supplies – even our drinking water – have to be shipped in from Rhodes, which makes our expenses high. The price of bread, however, is fixed by the Greek government, so we are working on a very small profit margin.”

Nevertheless, this remarkable jack-of-all-trades said he and his wife would be quite happy to remain on Kastellorizo. “It is a beautiful island and the people have been nice to us,” he confided.