Was there such a thing as ‘fashion’ in ancient Greece? Picture a ‘typical’ ancient Greek, and no doubt he/she will be wearing the ubiquitous chiton, perhaps better known in its later Roman incarnation as a toga, regardless of the sex, time period or the wearer’s place of origin.

Closer inspection, however, reveals that ancient Greek dress was not simply a matter of long white robes. Styles, material colors and patterns, as well as accessories were by no means standardized. Thucydides, for example, tells us that at one point, older men gave up wearing their hair in a knot fastened with a golden grasshopper. And, as they have throughout the centuries, women employed a variety of ingenious devices to enhance their beauty.

Homer makes few references to clothing, though the production of cloth, one of a woman’s major domestic responsibilities, is mentioned many times; Penelope, of course, being the best known weaver. The process of making material was a. lengthy one involving cleansing the fleece, dying and teasing it, ‘carding’ (combing, so that the fibre or fluff was arranged as lengthways as possible) and spinning. In the Odyssey, Helen had a golden distaff wound with violet-blue wool and a silver basket that ran on wheels, filled with dressed yarns.

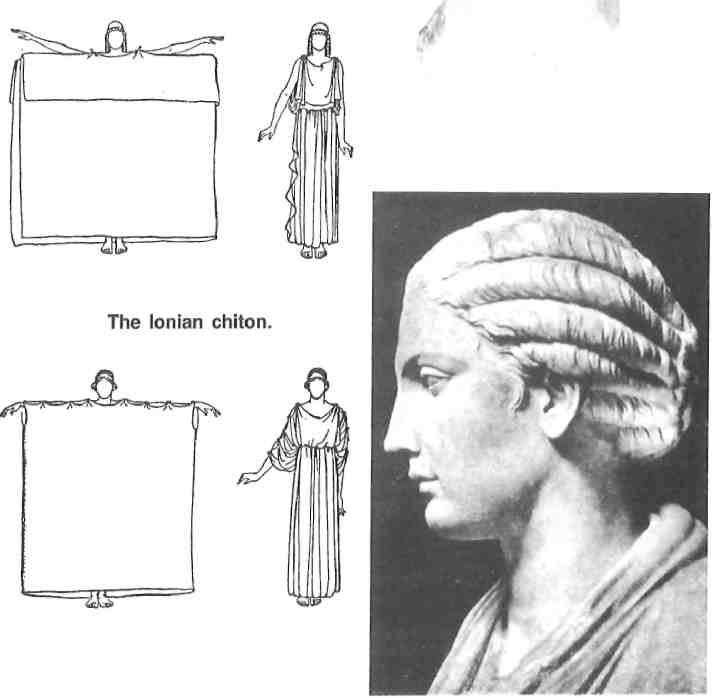

After the material had been woven, very little cutting was required to make the under tunic, or chiton, which formed the basis of men’s and women’s clothing. In Archaic times, the woman’s chiton, or es£/ies,comprised a plain piece of material about the height of the woman, and twice the span of her arms. The top third was folded over, and then the doubled material was slipped over the shoulders and fastened with broaches, made originally from the leg bones of small animals and later from metal, still retaining the same name of fibulae. The Archaic chiton was open at the sides, held together by a girdle at the waist, giving the impression of two separate garments. Herodotus calls this the Dorian chiton.

In the early sixth century, the so-called Ionian chiton was introduced. This appeared more like a dress, being sewn up at the sides and not folded over at the top (thus more economical with material). The material used was either linen or, sometimes, muslin, and, far from being invariably white, it was sometimes striped or had fringes added. Saffron and red were favorite colors. Later, Asian influence brought new, more vivid colors: pinks, blues and yellows. There were also materials decorated with gold thread or embroidered with flowers, initially reserved for statues of the gods or for actors portraying them. Later, however, a rather clever law was passed in Athens obliging hetaerae (concubines) to wear such materials, thus making them instantly recognizable.

The male version of the chiton was normally much shorter than the female (although for those with draughty jobs, like charioteers, it might be longer!). If worn under armor, the tunic would be tight-fitting. Men of high rank normally wore white, while peasants wore a natural wool color.

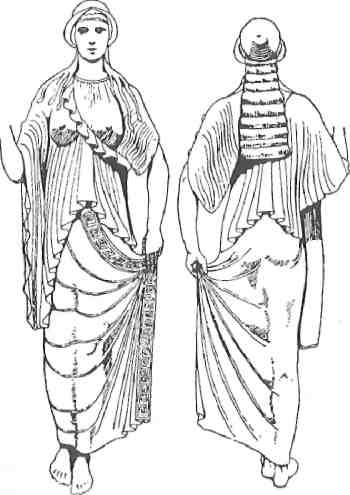

No self-respecting Athenian lady would leave her house without puting on her imation, or mantle. This plain rectangular piece of cloth could be worn in various different ways -perhaps thrown over the shoulders like a shawl, draped over the right shoulder and under the left arm, or pulled up over the head as protection from the sun. They came in varying sizes, too, larger ones for cold weather being more like a cloak. The imation often had decorative borders, and the folding and hanging of it, in such a way that the folds apeared like pleats, must have required great skill.

The kypassida, a sort of short jacket that buttoned at the front, was sometimes worn instead of the imation. No hats, as such, were worn by women, though on a particularly hot day a skiada, or sunshade, might be carried. Wealthy Athenian ladies often wore a peplo, or veil, like the one the goddess Athena wore on the day of the Panathenaia.

LOWER LEFT: Ioanian chiton.

RIGHT: Young girl with so-called melon coiffure (head in the Vatican)..

Berenike Bronze Head at Naples.

Indoors, shoes were not normally worn by the ancient Greeks, and sometimes not outdoors either. According to Hesiod, country folk wore oxhide sandals lined with felt. Short women sometimes wore shoes with cork platform soles to increase their height.

Hairstyles were many and varied in ancient Greece. One of the most popular was a centre parting with the hair tied back with a colored ribbon. Some women wore their hair in a bun, right on the top of their head, others had a short straight fringe across the forehead. Sometimes, ribbons were tied around the forehead, decorated with a small metal button at the front. Iron curling tongs were used to create artificial curls, and the present day Greek preference for blond hair can be traced back to classical Athens when many women dyed their hair. Later, Lucian criticized the frivolity of women who used machines to make curls and squandering their husbands’ fortunes on Arabian dyes.

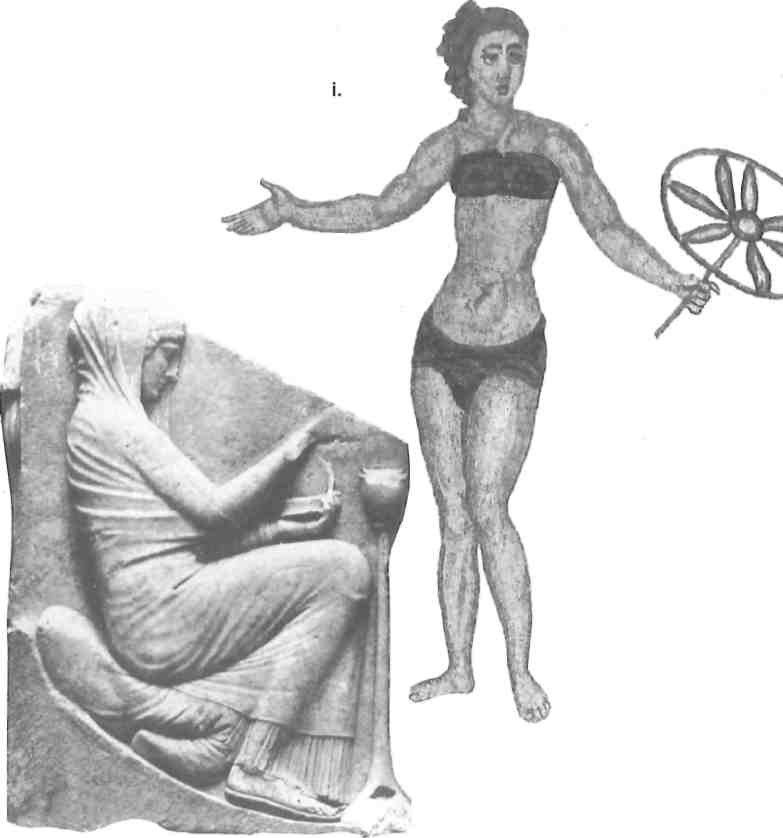

Hair dying was not the only artificial means of beautification used by women. Wigs were worn, and thin women employed a type of bustle to improve their figures. Despite the basic principle that the body should not be restricted by clothes, bras were not unknown to Athenian women. The use of make-up was another eastern habit brought to Greece by tradesmen and travellers. In fifth century Athens, women used lead to whiten their faces. Lips were reddened, and rouge, made either from seaweed or the roots of plants, was used. Eyebrows were emphasized with soot, eyelids were darkened with kohl, while mascara was made from cowdung(!) or from a mixture of egg white and gum.

Other necessary additions to the Athenian lady’s boudoir included wrinkle creams, mastic oil as a deodorant, coconut or palm oil for the breasts, and extract of thyme from the throat and knees. All were applied by means of special brushes (christeres) or simply with the fingers. Even hair-removing cream, made from a rather lethal mixture of asbestos and arsenic, was used.

Bracelets – sometimes called opheis (serpent) or drakontas (dragon) after their shape – were favorite pieces of jewellery. Anklets (perisphyria or chrysas pedas), necklaces (periderea or” ormous) and earrings were also popular. Girls normally had their ears pierced at an early age.

RIGHT: A bikini.

RIGHT: Nike flying, III century or later (Metropolitan Museum).

Generally speaking, despite the jibes of the satirists, stylishness was a much admired quality in a woman, and one to which the Athenian lady devoted a great deal of care and attention. By Pericles’ time, some women, exceptionally skilled in textile production, had begun to make more clothes than were required by their own families and, with the assistance of slaves and free workers, set up their own cottage industries, the ancient forebears of today’s great fashion houses.