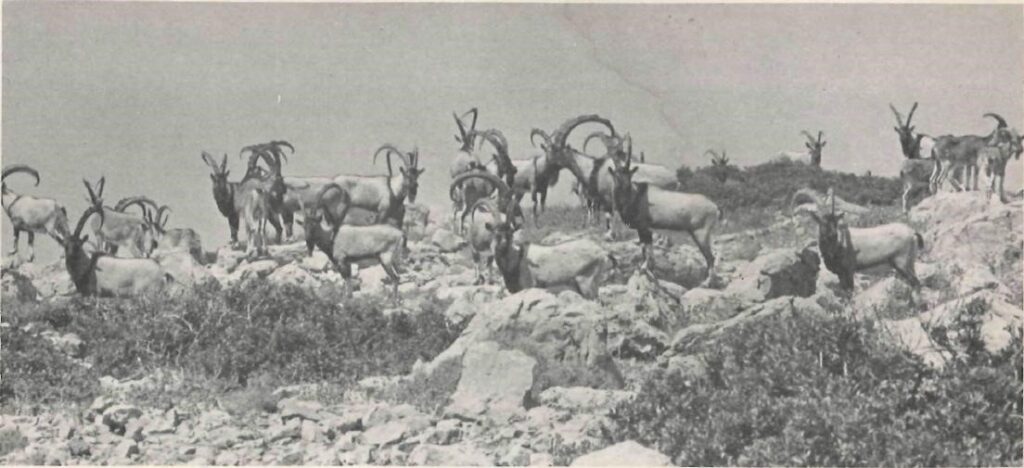

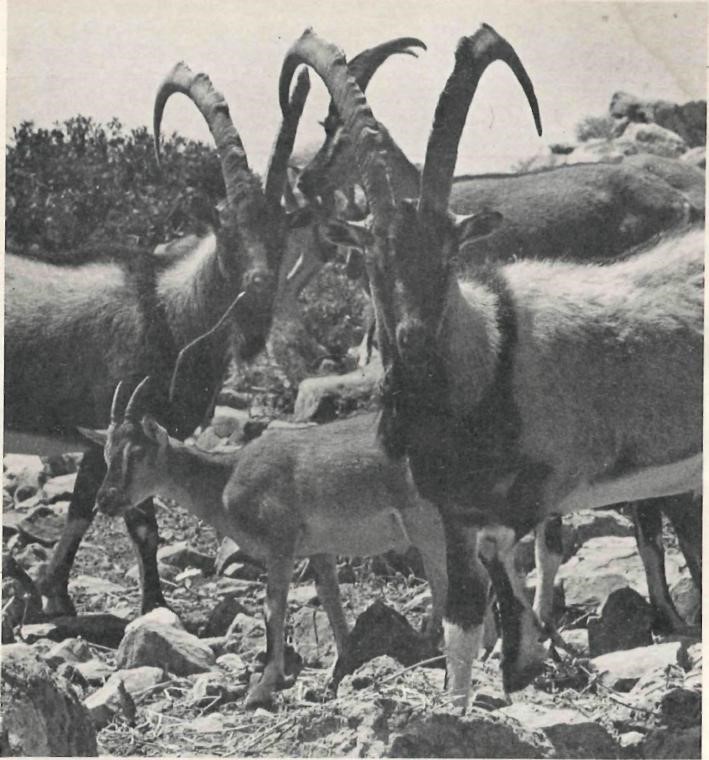

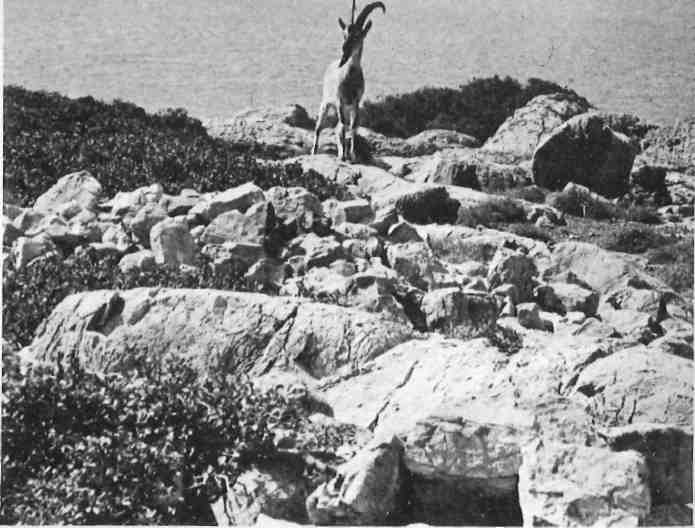

The Cretan goat complicates its own image problem by being so elusive. It is never seen in the wild by the casual traveller and has seldom been photographed even by professionals. With good reason do Cretans call it simply the kri-kri, a dialectal corruption of agrimi, ‘the wild one’. But in one of those ironies typical of our age, anyone can now see a wild goat in the little zoo at the National Gardens in Athens or at the small collections of animals in Iraklion, Hania, or Rethymnon on Crete.

Crete’s wild goat presents a fascinating if not altogether unique phenomenon: An elusive creature for which we have documentary evidence going back many thousands of years. A wild animal that interacted with human beings on many levels over those millennia. A rarity that survived into our own age only to come close to total extinction. A species so endangered that it must now be hunted for its own good. Surely such a creature deserves a genealogy if not a coat of arms.

There is no need to exaggerate the novelty or priority of Crete’s wild goat. Zoologically, as indicated by its scientific name, Capra aegagrus cretensis (‘Cretan wild goat’), it is not even a species unto itself but a subspecies. It is, moreover, a cousin—or perhaps an uncle—of the domestic goat, Capra hircus.But the Cretan wild goat is not the same species as the wild goats found elsewhere in Europe, over in Sardinia, or up in the Alps, and known by such names as the ibex and chamois. The Cretan goat is, rather, a subspecies of the wild goat now pretty much restricted to the mountains stretching from the Caucasus down into Iran and Pakistan. The common name for this goat has traditionally been the bezoar, which is derived from the Persian.

All this points to how the wild goat came to be on Crete in the first place. For millions of years, Crete was linked by land to Asia Minor (and possibly even to North Africa). Various animals passed back and forth until approximately one million years ago when profound convulsions submerged a vast area of land, leaving Crete isolated along with other protruding islands in what we know as the Aegean Sea. This also left the mountain goat from Asia stranded on Crete along with several other species of animals—including an elephant and a hippopotamus. Fossil remains of all these animals have been found in ancient geological deposits on the island.

So there the goat remained, isolated on Crete for hundreds of thousands of years, evolving only a few minor variations—in its colouring and horns, for example—that rate it as a subspecies. And there it was when the first human settlers arrived, about 6500 B.C. according to current thinking. This happened to be about the time that the goat was first being domesticated by the people of southwest Asia, the very region from which the earliest Cretans probably came. Whether by these very first settlers or by later groups, the domesticated goat was brought to Crete as part of the Neolithic cultural baggage, and judging from the finds of bones at Neolithic Cretan sites, including Knossos, the wild goat was soon being exploited along with its domesticated relative.

Some of these wild goats, especially young ones, may have been captured alive by early Cretans, but most were hunted down—for their flesh (for eating), their skins (for garments), and their horns (for bows, Arthur Evans suggested, among other uses). Children of a cattle culture are apt to overlook the great appeal of the goat, even while making much of the fact that the goat can live in places, and survive on vegetation, that other animals avoid. What matters to goat people, however, is that the goat turns those unpromising elements into a plentiful and nourishing milk supply, which people turn into cheese. To this day, most Cretans owe more to goat’s protein than to cattle’s. Of course, the wild goat was not usually available for milking. In a generalized sense, however, the plenitude of goats merged in the minds of the ancients. The domesticated species provided the practical half, which, paired with the wild species’ vivacity, formed an image that transcended both.

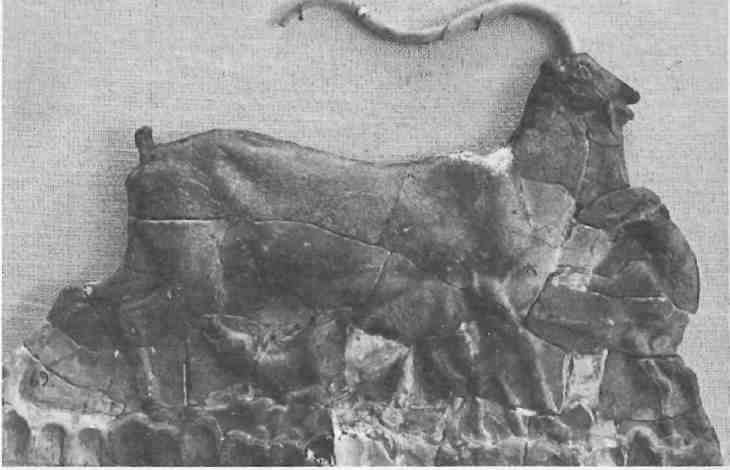

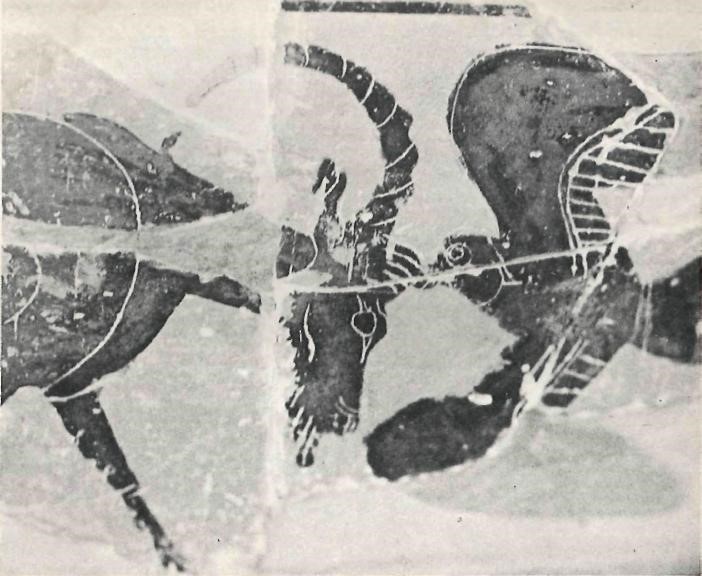

The wild goat was accepted as another item on the ancient Cretans’ ‘shopping list’, but it also assumed another role—that of a religious icon. Any attempt to say exactly what the Minoans ‘believed’ is tricky. For all the insights granted by the decipherment of Linear Β in the last twenty-five years, the experts are still forced to fall back on many inferences, analogies, and speculations. Still, and without claiming that the early Cretans observed a literal totemism, it seems evident that the Minoans felt a strong kinship with animals such as the goat on which they were so dependent.

There is nothing startling about this, since peoples long before and all around the Minoans had many associations with goats. On Crete, the goat seems to have been one of several archetypal animals associated with the Great Mother, or Nature Goddess, who in turn seems to have dominated Minoan religion. Each of the animals represented some different aspect of the goddess: the bird, her light- celestial aspect; the snake, her dark-chthonic aspect; the goat—thanks probably to a combination of its edible flesh, its generous milk, and its sheer sprightliness—reflected the fecundity of nature and, hopefully, the fertility of humans.

Since the Minoan Great Mother was very likely a moon goddess as well as a fertility deity, goats were probably sacrificed to her in this moon aspect by women. Indeed, there are grounds for believing that the goat, in its link with the female-fertility deity, came to be crowded out by the bull, which was associated with the male god and the concept of kingship that usurped the authority of the earlier Great Mother. One thing is certain through all this speculation: there is a continuous chain of evidence—votive offerings, sealstone carvings, painted vases and sarcophagi, and other forms—that the goat played a part in Minoan religion.

There is another source of illumination of this Minoan religion: the many references in later Greek myths, poems, and other writings. Here again, we must be wary. These works were many centuries and several culture-layers removed from the Minoans, and although it is fair to assume that Minoan seeds lie below many Classic blooms, it is also true that there was much cultivating of the original stock. Hesiod, for instance, writing circa 700 B.C., told how Zeus was born to Rhea. She, fearing his father Cronus would devour him, hid the babe Zeus in a cave on ‘Goat Mountain’ in Crete, and there the infant was suckled by the she-goat Amalthea. Later tales claimed that Zeus, in gratitude, elevated Amalthea to the constellation of Capricorn, and that one of her abundant horns became the Cornucopia, the ‘horn of plenty’.

The point about all such stories is not that they are verbatim Minoan beliefs—the later tales are clearly literary embroidering—but they do attest to a common impulse, the age-old regard for the goat as a bounty of Nature. Hardcore pantheism was somewhat refined by Classic Greek religion, of course, with its anthropomorphic-Olympian cast, but even then the goat was never completely banished to the barnyard. The Maenads, or Bacchae, those devotees of Dionysus who roamed about in frenzied orgies, devoured the raw flesh of goats. There was Pan, half-goat and half-man, who eventually became the very embodiment of pagan religion. Even Hera, that most dignified matron, was associated with goats as a goddess of fecundity. (Not so incidentally, Hera’s name appears on a Minoan Linear Β tablet as the recipient of an offering of wool.)

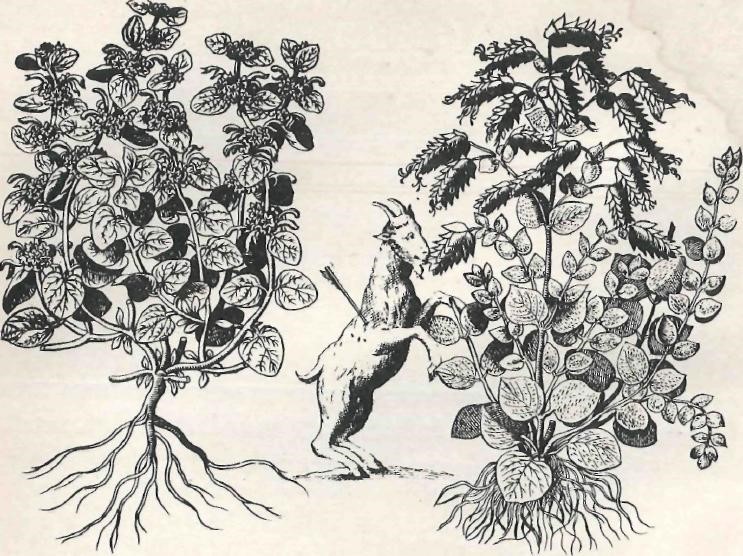

As for the wild goat in Crete itself during the Classic period, it enjoyed still more projections. In one myth, Apollo—evidently worshiped on Classic Crete as a hunting twins of Akakallis, a daughter of Minos, and these were suckled by a goat. And another tale surfaces: the Cretan wild goat, when wounded, was said to seek out an indigenous Cretan herb, the dittany (Origanum dictamnus), and so cure itself. Since a wounded goat tends to prove elusive, and since the dittany does at least have a bit of ‘pep-up’ power, the link was understandable. Aristotle himself was not above recounting this story. Many other ancients, including Theophrastus, Cicero, and Pliny, repeated it, but none more charmingly than Vergil. In the Aeneid he tells of the wounding of Ascanius:

Then Venus, all a mother’s heart,

Touched by her son’s unworthy smart,

Plucks dittany, a simple rare, From Idha’s summit brown,

Well known that plant to mountain goat,

Should arrow pierce its shaggy coat.

With the decline of the ancient world, the wild goat of Crete vanishes in the Dark Ages along with everything else. Christianity, a few Arabs, Byzantine Greeks—all were absorbed by the islanders, until in 1204 the Venetians took over and imposed their own social and economic forms. If these were dim centuries for human Cretans, the wild goats evidently thrived. When the French naturalist Pierre Belon came through circa 1550, he reported seeing sizable troops of wild goats in various parts of the island. Even the occupation of the Turks, which began around 1650, left the wild goat population intact. The great French botanist Tournefort, who travelled on Crete around 1700, could write that ‘the wild goats … run up and down these mountains in herds’—and he was referring to a range way over in eastern Crete. Through the nineteenth century, travellers reported considerable numbers of wild goats in many mountainous regions of Crete.

Yet somewhere between the late nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century, Crete’s wild goat population was decimated. By 1933 one Cretan was writing, unfortunately it is doubtful whether a single specimen still exists.’ This was a city-dweller speaking, but the fact is that the wild goat had been forced to retreat primarily to one area, the White Mountains of western Crete, and even more specifically, the Gorge of Samaria. This remote and splendid gorge, extending some ten miles up from the southwestern coast, is—along with the wild goat and the pink-flowered dittany—one of Crete’s indi-genous natural wonders. At least it was fitting for the goat to end up there, the traditional hiding place of Cretan refugees from oppression—and authority.

How had this apparently sudden decline come about? It is hard to explain, since even now modern forms have barely intruded on the wild goat’s natural terrain. Certainly there have been few roads or vehicles until quite recently, no industry or urban development in those areas of Crete frequented by goats, and no chemicals to pollute the wild goats’ sources of water and food. Probably the general bustle and expansionism of our century was enough to send the goat into its retreat: in that sense, Sir Arthur Evans is as responsible as anyone. But I would like to nominate a more specific villain: the rifles that came into the hands of so many Cretan males during the nineteenth-century struggles against their Turkish overlords. Then, of course, their more efficient twentieth-century replacements, plus telescopic sights, tightened the noose.

Whatever the causes, the wild goat of Crete was so threatened that in the early 1950s the Greek state set aside three islets off Crete’s northern coast as game preserves—Dhia, Agios Theodoros, and Agios Pantes. Captured wild goats were brought there over the years, and since then the islets’ populations have increased to several hundred —over 500 alone on the largest, Dhia, just off Iraklion.

Whether the goats being preserved are ‘purebreds’ is in some doubt. Over the years domesticated goats have occasionally been loose on the islets. Observation of the goats’ colouring and horns indicates many are not of the pure wild variety. But considering the fraternization that undoubtedly took place between the wild and domesticated goats over the millennia, this Cretan subspecies is probably no more or no less ‘pure’ than ever.

But one of the most surprising twists in the long saga of Crete’s wild goat came when the government announced in 1977 that it was going to allow hunting of the animal—on Dhia. The idea behind the preservation project had been that when the islets’ population seemed sufficient, the goats would be re-established in the wilds of Crete, and there has been some restocking of the old habitats. Meanwhile, life on Dhia has been so unnaturally easy the population has gotten out of control. For many years now, the government has killed off thirty to forty goats each year (and sold the meat in Iraklion to raise money for the expenses of the project) Now the intention is to encourage hunters to go over to Dhia. However, the costs involved—in special licenses, in a charge per goat killed (a limit of two), and transportation to Dhia—restrict the opportunity to only the very affluent. Furthermore only the elderly males can be shot, and considering they cannot really get away, it is questionable what kind of sportsman this will appeal to.

There is one last branch on this animal’s family tree. In the late 1940s, some Cretans were seeking a way to express their gratitude to the American people for the aid given to Greece in the aftermath of World War II. From Minoan vases to El Grecos, from Kazantzakis’s works to—some would insist—a fragment of Lost Atlantis, there were many homegrown symbols to choose from. What they presented to President Harry S. Truman was a Cretan wild goat.

A wild goat as Crete’s totem? The goat, with its foul odours, cloven hoofs, ruttish behaviour, downright orneriness? The butt of jokes and the butter of obstacles? That may be. But the wild goat remains the most fitting symbol of Crete’s persistence through thousands of years of ‘blood, sweat, toil, and tears’.