It was the Greeks overseas who first conceived of a revolution that would free Greece from the domination of the Ottoman Empire and lead to the creation of a modern Greek state. When the war broke in 1821, Philhellenes in Western Europe joined the struggle. Within six months at least two hundred appeared here to participate. The vicissitudes of the war during the next years led to a waning of European interest in the Greek cause. Although the appellation was not coined until 1825, the first true ‘Philhellenes’ were that romantic battalion which accompanied, or followed in the wake of, Byron’s last pilgrimage to Greece during the years of 1823-24. Pietro Gatnba, the brother of Byron’s mistress, described them in Missolonghi in 1824: ‘…English, Scotch, Irish, Americans, Germans, Swiss, Belgians, Russians, Swedes, Danes, Hungarians and Italians. We were a sort of crusade in miniature.’

The first Greek loan was floated on the London Stock Exchange in February, 1824, in the name of the London Greek Committee, the most important philhellenic organization in the world.

In the same year Scotland produced Ά Scottish Ladies Society for Promoting the Moral and Intellectual Improvement of Females in Greece’. In America, a cross was consecrated to the cause on Brooklyn Heights in New York, and the ladies of Pearl Street contributed 733 pieces of women’s clothing. In Paris, Rossini dashed off an opera, The Seige of Corinth, which opened in 1825, and French painters worked feverishly to satisfy the public’s appetite for ‘Greek massacres’.

Although George Finlay began as one of the most romantic of the Philhellenes (throughout his life he was proud to speak of his acquaintance with Byron), his Scottish pragmatism eventually rose to the fore. The acerbity of much of his History of the Greek Revolution, written thirty-five years after the events, results from an elderly man’s realistic appraisal of a youthful dream. His conclusion was that overseas Greeks and the Philhellenes were only a catalyst to the Revolution, which he believed was a truly nationalist movement in which the Greek people were not merely the instruments but the chief performers.

For George Finlay 1823 was a year of decision. He began it in Gottingen, a student of twenty-three, studying Roman law as a prelude to entering the Scottish bar. He ended it in Athens, an ardent Philhellene in search of a role in the war against the Turks. The village of Athens, lying in ruins at the foot of the Acropolis, was to become his home for almost fifty years. But not at once. Greece had yet to be freed. Thus Finlay served with the unscrupulous chieftain Odysseus on Parnassus and Byron at Missolonghi, but because of malaria he had to return to Glasgow. With his health recovered (and even though he had passed the civil law examination) he sailed to Greece as soon as possible on Hastings’ famous ship, Karteria, in May 1826. The ship’s boilers, however, blew up on the outward passage and Finlay did not see Athens again until 1827.

Law was now a thing of the past; even Glasgow and his beloved Clyde were to become cherished memories, very occasionally to be visited. Finlay’s goal was to help build the new independent Greek state. And so he settled here. By the time Athens was chosen as the new capital, Finlay had a main residence in the city, a house that still exists on Adrianou Street, the most fashionable rue of its day; a farm at Liosia, thirty kilometres north of Athens on the other side of the National Highway from Afidnai and a retreat on Aegina, the Red Tower at the edge of town. To share his adopted country, Finlay, then in his early thirties, brought a wife from Constantinople, the Armenian Nectar Trevinian. They had one child, Helen.

For several years Finlay was a tireless man of action: city planner, bank consultant, overseer for the building of the Anglican Church, farmer. When his farm failed, he realized the futility of trying to improve the land. And so he turned to what he called more ‘sterile’ occupations, to criticism, journalism, archaeology, but above all to history.

Finlay’s supreme achievement, the writing of Λ History of Greece (under foreign domination), fully occupied his maturity. In 1843 he published Greece under the Romans; in the fifties he dealt with the Byzantine and Greek Empires, and Greece from the arrival of the Crusaders to the conquest by the Venetians; and finally, inl861, he told the story in which he had participated, the History of the Greek Revolution. Two years after his death, Oxford Press reissued the series in seven volumes, edited by H.F. Tozer, but with revisions, additions, and much rewriting by Finlay himself.

These volumes remain a worthy monument, not merely for their scope, which is unequalled, and learning, which is always great, but also for their signal awareness of the necessity of understanding Greece as it is, if one seeks to interpret her past. Finlay’s contemporaries recognized his stature as a historian and he received honorary degrees from Edinburgh and Cambridge.

Although he said of himself in 1861, Ί am declining into the vale of years, and there is nothing left for me but to walk along calmly and quietly’, others might have had difficulty in noting such resignation. As correspondent for The Times from 1864 to 1872, he regularly contributed pungent articles on Greek affairs, as he sought, to the end of his life, to ensure that Greece build her future on sound institutions. Only one who held his adopted country so dear could have spent so much of his strength on her upbringing.

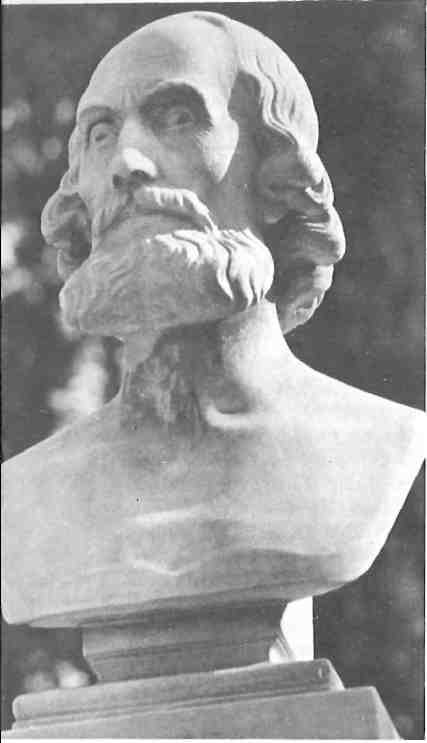

Old age and sickness eventually led to the vale’s edge, and on January 26, 1875, George Finlay died. He was buried in the Protestant section of the First Cemetery. His grave still stands, proud, even defiant. A chaste neo-classic sarcophagus bears an inscription, which also recalls his wife Nectar, who survived him, and his daughter, who died at the age of ten. Finlay’s bust rises above their tomb, his craggy face and critical eyes turned towards Aegina and the lands and seas he loved as his own.

THE REAL FINLAY by Joan Hussey

Photographs by Eugene Vanderpool

George Finlay died in Athens a hundred years ago. In the spate of books which have recently commemorated the hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Greek Independence, he regularly appears as an ardent philhellene of a rather sardonic turn of mind. Even the historian William Miller, who lived in Athens and had leisure to peruse the Finlay Papers, moans about Finlay’s failure to present ‘a bright picture of what was going on around him’ and deplores what he describes as ‘tireless re-iteration of Greek national deficiencies’. In working through the formidable and unwieldy collection of his Papers (which I am in process of editing) I found, however, a somewhat different personality emerging. To regard Finlay simply as a man devoted to the Greek cause, over-critical and contentious, is to give a false, or at best, an incomplete picture.

The truth is that Finlay has been regarded too much as a philhellene and then a critic of subsequent events in the Greek Kingdom. Perhaps this is because modern historians of nineteenth-century Greece have had neither time nor opportunity to work systematically through the mass of heterogeneous material which Finlay has left. But the real Finlay cannot be kept in the water-tight compartment of Greek politics. He must be approached with a keen awareness both of the background of Victorian Britain and of the characteristics of the Scottish people, for the man who emerges from an impartial study of all his papers — not just those relating to Greek politics — is a Scot and a Victorian, a nineteenth-century individualist with that remarkably wide range of interests which marked his generation and which, in Finlay’s case, included a deep devotion to Greece and to the Greek people.

Finlay was born in 1799 and his formative years were spent in Scotland. In later life during his periodical visits to Britain,he used to go back to Castle Toward where he was brought up. The great house on the shores of Loch Striven and the Clyde still stands looking out towards the distant islands of Bute and Arran, behind which the hills of Argyll rise steeply. Finlay’s friends knew how deep was his attachment to this countryside. As often with the Scottish people, Finlay was a romantic, though he would have been the last to admit this and he even said in his Journal that he was a dull prosaic person. Byron saw through him though, and remarked that his very presence in Greece pointed to the romantic streak in his make-up. But Finlay was essentially reserved and found it difficult to express his emotions. Very occasional stray remarks about Castle Toward, or references to missing his wife and child when traveling abroad, are rare exceptions revealing the depth of his personal feelings.

In spite of his affection for Scotland, he chose to settle in Greece. His endless troubles over his lands constantly recur in his correspondence where he fulminates against the annoying tax on produce and the theft of his acorn crops or the crown appropriation of some of his ground in Athens. Though firmly and happily settled in what he called his ‘cell under the shadow of the Acropolis’, from time to time Finlay travelled around the countyside. He has left meticulous topographical notes, particularly in his long letters to Colonel W. M. Leake, who used this material in his own masterly topographical studies of Greece. Finlay also explored the Aegean islands and went to Turkey, Egypt and parts of the Middle East. He

left an amusing account of the astute old pasha of Egypt, Mehmet Ali, whom he visited in Cairo, including details which he had picked up about ‘the female parties in the harem’, as well as shrewd comments on the pasha’s attitude to Britain. His diaries and account books reveal all the hazards and trials of nineteenth-century travel — the long quarantines, the fight against ‘fleas and fleecing’, the struggle to get back one’s passport, arrangements for the transport of essentials such as beds and tables, and, in Finlay’s case, even a writing desk.

Side by side with the rich details of everyday life is a wealth of material on the problems of contemporary Greece, not just politics and diplomacy — though there is plenty of that — but practical suggestions for the administrative and economic life of the revived Greek nation with emphasis on healthy and autonomous municipal and provincial governments and sound agrarian development. In all this Finlay was intensely practical and found it difficult to conceal his impatience at the long delay in producing a constitution for Greece and at the dilatory attitude of the Great Powers and the Greek Government.

He warmly praised the mass of the Greek people but had little use for Otto (chosen by the European powers to be King of Greece), for the Bavarians who followed in Otto’s wake, or the Phanariots, the wealthy and patrician Greeks from Istanbul who settled here after the outbreak of the revolutionary war and who, according to Finlay, ‘look in books for what ought to be done’ and then wasted any available funds. A sensible agrarian policy and good communications were far more important, he stressed, than splendid uniforms and lavish salaries for deputies and generals. ‘Greece had more need of beeves [oxen] than Bavarians, of eating than being eaten’. Finlay’s cutting criticisms are often quoted but, in fairness, his constructive and practical assessment of the general needs of the people should also be emphasized. To accept at its face value (as some do) Finlay’s own statement that he was a failure as a farmer and therefore turned to scholarship is to oversimplify and does injustice to his shrewd observations and to the sound principles which he wished to see applied to the Greek economy.

It is, of course, true that Finlay was also a scholar and his love of Greece is reflected in the field of his choice. His main work is his History of Greece. This runs from 146 B.C. to A.D. 1864 and is still of value, both for his treatment of the medieval period, with its perceptive comments, and more especially for the nineteenth century, where it becomes a contemporary source, often from eyewitnesses. And, indeed, there is contemporary material to be gleaned throughout the History because Finlay had a habit of comparing earlier, particularly Byzantine, trends with Greek life of his own day. His books, at present scattered about the shelves of the library of the British School in Athens, were carefully listed by their owner (who also left notes on volumes lent and never returned, adding ‘and I cannot remember who borrowed them’). Many contain illuminating, pencilled marginalia and their astonishing range reveals the extent of Finlay’s interests, as well as the seriousness with which he took his work as a historian. He did not confine himself to literary material but realised the value to historians of first-hand acquaintance with the country itself. As he remarked to Leake in 1847, apropos of his criticism of Grote’s history of Greece, ‘The necessity of personal observation seems greater in Greece than anywhere else to understand the country, the people and the remains, and really Grote has been guilty of neglect in not visiting the country which must seriously injure his work. Some scholars seem to think that Greece is in Germany.’

Like many nineteenth-century scholars, Finlay’s interests were encyclopedic. His Papers include letters on modern politics, cuttings from newspapers and journals, ranging from prehistory, archaeology and numismatics to contemporary lampoons and life in Australia. He was tenacious and meticulous, even tracking down books lent and not returned, pursuing loans not paid or property rent long overdue. He had a passion for minute documentation — if it can be dignified by that term. His little notebooks record the smallest details of his personal accounts over the years, the modest cost of a bath when staying in France, or the amount of his offertory in the cathedral (the same as for his bath), or the price of the silk dress purchased to take back to Mrs. Finlay (his one extravagance on this particular journey).

Yet after a hundred years the image of George Finlay is predominantly that of a rather sarcastic and critical man, even if this judgment is sometimes tempered by a tribute to his love of Greece. It is fitting that a century after his death the balance should be restored. There is so much in his Papers that points to a stimulating and generous man and a delightful companion. Finlay’s old friend, the Bostonian Samuel Gridley Howe (an American Philhellene whose impressive career as a philanthropist and educator is fre-quently eclipsed in people’s minds by that of his wife who wrote ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’) knew that the reserve and critical outlook concealed ‘a kind heart and delicate feelings’. It is only necessary to read the letters which Finlay received to realize the truth of Howe’s judgment. Finlay’s correspondents included such men as John Stuart Mill, Walter Pater, Fallmerayer, von Hahn, Prokesch-von-Osten —diplomats and scholars from almost every European country as well as the United States. They respected his intellectual qualities, and, more than that, they found in him a kind and congenial friend and on occasion enjoyed his family circle as well. But he had another category of correspondents, men and women who are scarcely, if at all, known. To these he was equally helpful and courteous, sending them articles on modern poetry, or taking them around Athens with as much care as he had shown to Gladstone when this statesman visited Athens in 1858. There was nothing perfunctory about any of Finlay’s personal relationships.

In fact Finlay’s outspokenness, whether on Greek politics or other topics, seems to have misled posterity and has given him an undeservedly bad, or, at best, a rather grudging and one-sided press. After all, even as far as Greece is concerned, Finlay gave praise to nearly all but the politicians, paying tribute after a very short time to Athens, ‘as civilized a capital as any in Europe’, and recognizing the potential of the Greek people. And he had many other sides besides that of the philhellene and historian. The truth is that his thought, outlook, activities, have not been viewed as a whole, nor has the temperament of the Scot been taken into account. It is fitting to ask that justice should be done to a man whose insight into contemporary politics and literature was balanced by a keen appreciation of the past, whose somewhat astringent pronouncements were tempered in practice by generosity and consideration, whose companionship was valued by a remarkably wide and varied circle — in short, a Scot and a romantic who made Greece his second home without ever forgetting Castle Toward in Scotland.

Quotes from Finlay

“Men who combine heroism and fraud ought to be praised only in French novels.”

On the Revolution

“From some circumstance which hardly admits of explanation, and which we must therefore refer reverentially to the will of God, the Greek Revolution produced no man of real greatness, no statesman of unblemished honour, no general of commanding talent.

The true glory of the Greek Revolution lies in the indomitable energy and unwearied perseverance of the mass of the people. But perseverance, unfortunately, like most popular virtues, supplies historians only with commonplace details, while readers expect the annals of revolutions to be filled with pathetic incidents, surprising events, and heroic exploits.”

On the English Loan

“Indeed, the Greeks generally appear to have considered the loan as a small payment for the debt due by civilized society to the country that produced Homer and Plato. The modern Greek habit of reducing everything to a pecuniary standard, made Homer, Plato & Company, creditors for a large capital and an enormous accumulation of unpaid interest.”

On the Philhellenes

“But it was by those who called themselves Philhellenes in England and America that Greece was most injured. Several of the steam-ships, for which the Greek government paid large sums in London, were never sent to Greece. Some of the field-artillery purchased by the Greek deputies were so ill-constructed that the carnages broke down the first time the guns were brought into action. Two frigates were contracted for at New York; and the business of the contractors was so managed that Greece received only one frigate after paying the cost of two… It will be seen that waste and speculation were not monopolies in the hands of Greek statesmen, Albanian shipowners, and the captains of armatoli and klephts. English politicians and American merchants had also their share.”

On the Phanariots

“The small stature, voluble tongues, turnspit legs, and Hebrew physiognomies of these Byzantine emigrants excited the contempt, as much as their sudden and superfluous splendour awakened the envy, of the native Hellenes.”

The passages quoted are from George Finlay’s, History of the Greek Revolution.