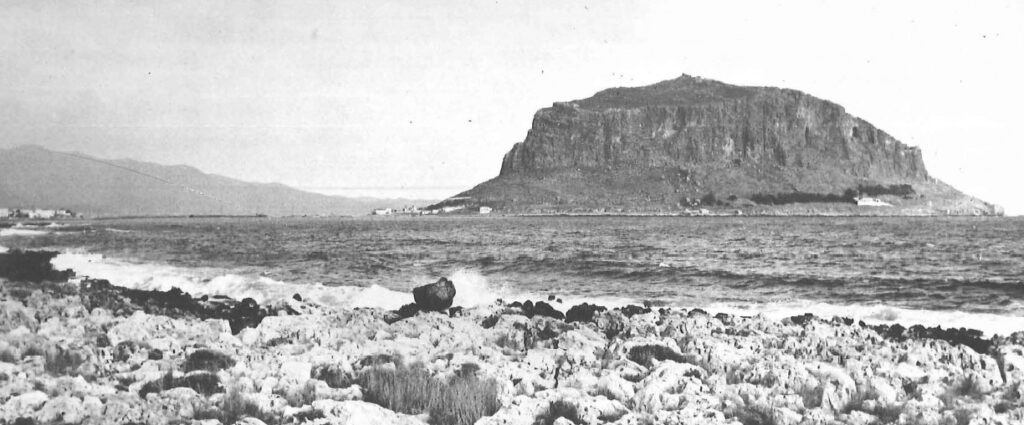

Greece is a land which prides itself on its Byzantine heritage almost as much as it does on the great civilization ol the Ancient Greeks. In many ways this love of the past has coloured most of modern Greece’s history with irredentist dreams of a restored Empire with its capitol, Greek once again, in Constantinople. The average tourist catches a glimpse of this past by going to the monasteries of Daphni and Osios Loukas and, perhaps, by making a quick trip to the Byzantine Museum. This may lead to the belief that the only thing the Byzantines did was build churches. With a bit of free time, some hardiness and, if possible, a car, a visit to the deserted city of Monemvasia will provide a rather more balanced view of Byzantine life. In this issue Alan Walker takes us on a visit to the Gibraltar-like fortress on the southeast coast of the Peloponnisos.

Monemvasia, which means ‘one entrance’, is joined to the mainland by a modern causeway which at one time was only a bridge. It was founded by refugees from the Slavic invasions in the seventh century who fortified the very top of its acropolis or citadel. Because of its impregnable position (and despite its lack of water), it soon became a thriving city not only on top of the rock but on the shore below as well. This ‘suburb’ on the shore was protected by walls in the shape of the Greek letter ‘IT, the base was on the shore itself and the sides ran up to the base of the citadel. The citadel, or upper city, is approximately three hundred metres in height. It is also surrounded by walls except in places where the sheerness of the cliff made them unnecessary.

Photograph by Eugene Vandevpool

The city of Monemvasia was well-known throughout medieval Europe (under its French name, Malvoisie) because of its richness, and because of its exports of wine, the famous sweet Malmsey. According to legend, the Duke of Clarence drowned in a butt of this wine. (Clarence, by the way, is another foreign corruption of a Greek place name — Clarentza, the great Frankish castle in Elis, the title to which passed to the English crown through the wife of Edward III.) Monemvasia resisted all enemies and only succumbed twice prior to the seventeenth century, to the Franks under Guillaume de Villehardouin in 1249 (it was returned as ransom to the Byzantines in 1262), and to the Turks in 1540. The walls of the city still stand to virtually their original height, as built by the Byzantines, with the major renovations added by the Venetians during their occupations in 1464-1540 and 1690-1715. These walls sheltered a very large population, so large, in fact, that houses had to be built both on top of each other and also over the roads which passed beneath as vaulted passageways. These narrow, winding, often covered streets can still be seen in the lower town, now inhabited by a small number of Greeks and foreigners. It is fairly busy in the summer but virtually deserted the rest of the year. (It is the birthplace of the poet Yannis Ritsos and many of his family are still there.) New buildings are forbidden but many of the houses have been recently restored. Since no car can enter, the visitor will find these narrow lanes pleasantly placid; you can’t get lost for too long and you can only be run over by donkeys or cats.

There are four churches still standing out of the original forty-four: the visitor will find them most rewarding from the outside. The cathedral on the central square is best viewed from above, in the upper city, whence its odd, Western, elongated plan becomes apparent when compared to the others. The climb from the lower town to the upper on the citadel is not very daunting: you make your way by any one of a number of small streets to the main path which winds its way up to the citadel’s main gate. This path is fortified with a number of cross walls and secondary gates which would have made it exceptionally difficult to attack. The iron-bound main gate leads into the city through a tunnel lined by guard rooms; you arrive at a small square where you can rest and contemplate the extraordinary sight of a whole city in ruins. An almost eerie affect is given by the large numbers of vaulted rooms which gape out like mouths of the earth itself. (Alas for romance, these ground floor rooms were probably designed to house donkeys!) There are several easy-to-follow paths which lead out of the square: one to the left at the tunnel’s mouth, one in the centre which leads directly to the restored church of Agia Sofia, and one on the right. The circuit of the city can be made in about an hour and a half and the hardy visitor will do just that. If you take the path to the left you will be walking beside the citadel walls; the view of the lower town is beautiful. You will soon come to a little domed building which is probably a Turkish fountain; above it are the great cisterns and the powder magazine. The cisterns can easily be recognized by the vast expanse of paved area surrounded by low walls; at the bottom end is a building which can be entered through a low door. This building contains one of the three giant cisterns of the upper city; the paved area was the catch basin for rain water. If you continue on this path (bearing left), you will arrive at the highest point of the rock on which are built the earliest, seventh – century, fortifications. It overlooks the whole upper city and the causeway to the mainland. Continue on the path, but along the north side of the citadel. On your left you will notice, below the fort on the lower slopes, a cross-wall with a gate in it between two spurs of the cliff. This was the only other gate of the city and was used for sorties and to enable the causeway garrison to retreat into the city if hard pressed.

You will soon regain the built-up area of the main city and, finally, Agia Sofia, a church built by Andronikos II (1282-1328). The interior is quite pleasing with some of the original frescoes remaining; the exterior lines are rather marred by a massive Venetian exo-narthex. The greatest glory of this church is its situation: it is built right over a cliff which is sheer right down to the shore, hundreds of feet below. If you’re feeling tired you can retreat to the square inside the main gate but you really should continue round the remainder of the city (it’s not far). The seaward tip is crowned by a diminutive Venetian guard post and commands yet another marvelous view. From here the walk back to the little square will take a mere ten minutes.

After walking back down to the lower town you may reward yourself with a bottle of beer in the kafenion. If the weather is right, you may also go for a swim, either off the rocks at the sea gate of the town or halfway along the road to the causeway where there is a sheltered area with steps leading down to the water (have a care since the water is deep, the shore shelves down steeply to a point about thirty metres out and then seems to disappear forming a very deep harbour). If you have a mask you may wish to amuse yourself by looking at the numbers of amphorae and pots which litter the bottom. Most are Medieval and Turkish but some may be late Roman. (Do not, however, amuse yourself by bringing them up with you since you may then find yourself with an all expenses paid visit to the local dungeons.)

Although the best time to visit Monemvasia is spring through autumn, the weather usually continues to be warm in the southern part of the Peloponnisos well into December. At this time of year, in winter, it can be deserted which means, of course, that you will have the undivided attention of the people in the area who may deluge you with hospitality in the off-season. In winter it can be wet and chilly which contributes to the Gothic-novel atmosphere with brilliantly sunny intervals for contrast. It is easy to see why John Fowles chose Monemvasia as one of the locations in his novel The Magus. It seems fraught with mystery.