A huge, white, sterile structure, its grounds are unlandscaped and its interior is unfinished. Like Kafka’s Joseph K. in The Trial, I wandered for over ten minutes through silent, labyrinthine corridors, leading to identical corridors lined with unmarked doors, until I was rescued by a secretary.

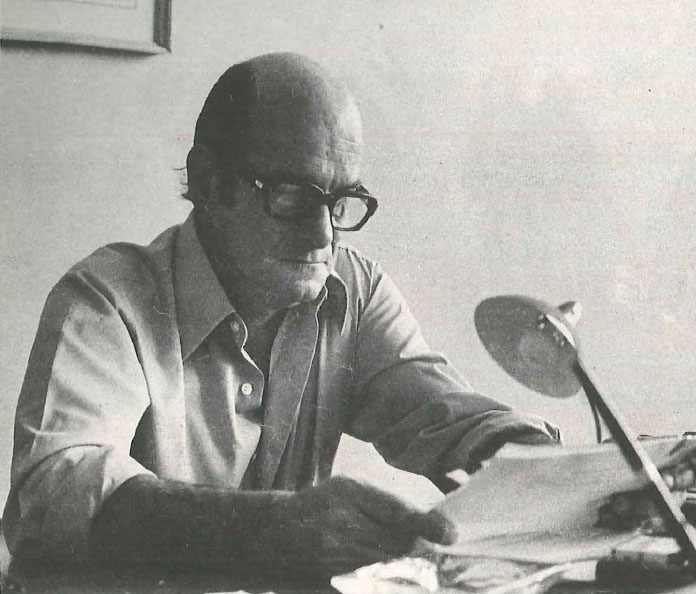

Alexis Solomos, a short, bronze-skinned man in his early fifties, sat behind a large desk in an unimposing office. ‘This building was a mistake from its beginning thirteen years ago,’ he observed. ‘There are no facilities for a cafeteria and there is not enough studio space, although we have many corridors which can be used for nothing!’ Alexis Solomos looked more harassed than when I had met him last year before he accepted his post as Assistant to the Director of EIRT, Greece’s national radio and television broadcasting corporation. He glanced frequently at a large television set in the corner. Its sound was almost inaudible. The show he was monitoring was a version of a traditional Greek fairy tale recently filmed at the network’s studios. As we spoke, he occasionally commented on the production with the critical eye of a director.

He had been invited to join EIRT, he explained, to improve the quality of the programs and to make them more ‘mature and civilized’. Although many consider his job to be a thankless task, Solomos has, nevertheless, succeeded in bringing more intellectual and stimulating programs to the local television screen.

Greek television came into existence in the 1960’s. When the dictators seized power, they immediately recognized the influence of television and set out to leave their imprint on it and to use it for propaganda purposes. The quality of programs was low, with heavy emphasis on war serials both locally produced and imported. The bulk of the news was dedicated to the activities of the members of the junta (although many believe that the effect of this intensive coverage was the opposite of that intended). During the Arab-Israeli War of 1973, a television viewer sitting through fifteen minutes of news showing the junta members cutting ribbons, making speeches, placing wreaths, was heard to quip, ‘The bombs will be landing on Athens before they get around to telling us about the war next door.’ Today there is a definite attempt to provide world-wide news coverage and intelligent documentaries produced here or abroad, as well as programs of broad, cultural interest.

‘Of course a whole world of people with vested interests in television opened a war against the new directors and against me, personally, saying that these new programs wouldn’t work. Now, happily, the programs have worked and everybody seems to be satisfied. All the serials made here, for instance, ·have been based on good Greek authors. We have also presented many programs from the French, German and Italian television networks, and the BBC. We take the best that they produce.’ During the past year television viewers have been treated to high quality series such as War and Peace, The Portrait of a Lady- and an Italian version of Jack London classics.

‘We have also begun a retrospective of film classics. And we have created a two-hour theatre show on Monday evenings presenting complete dramas, live and taped. As a matter of fact, we are filming one at this moment in one of our studios. In addition we take filmed drama from foreign companies, the Shakespeare Festival Theatre, for instance.’

One neglected segment of the population, however, has been the children. Save for puppet shows, cartoons, contrived children’s programs and British and American adventure series, which, it may be argued, have an indirect educational value for culturally deprived children, there are no special educational programs such as Sesame Street.

‘We haven’t arrived at this point yet in Greece. We have had many offers from nursery school teachers but none of the ideas presented so far have seemed worthwhile. I’ve seen many foreign programs, but unfortunately they cannot be brought here because they lack the special approach our children need. Some educational programs for older children are being planned for September in cooperation with the Ministry of Labour. I’m not very enthusiastic about this because … I prefer education to come through amusement which has a message.’ Pointing to the program he was monitoring in his office, he observed, ‘This fairy tale, for instance, is the first time that a children’s story has been created here … This one is a demotic tale that has survived in villages. We didn’t want to do international stories like Little Red Riding Hood.’

The gist of a report submitted earlier this year to the government by Hugh Greene, the former director of the BBC, was that Greek television should be a private enterprise, free of bureaucracy, and not a state institution. ‘Sir Hugh did not give us details … For instance, he did not watch any programs … but whatever I mentioned I wished to do with television met with his approval. I took encouragement from our talks with Sir Hugh.’ Solomos said. ‘Of course what we must do is create a more visual and mobile presentation of shows. At the moment much of Greek television is static theatre or static talk. We haven’t succeeded in creating a “live” approach. I also think our news broadcasting is very bad, but I haven’t yet had any direct kind of responsibility for the news. I will soon turn my attention to this.’

SOLOMOS’s immediate superior at EIRT is Angelos Vlachos, the noted writer and diplomat. ‘If there is a program decision, I make it and then I tell Mr. Vlachos and if he agrees he signs the proposal. I cannot put my signature on anything. My job gives me no administrative power to sign, hire or fire people. But programs are done according to what I say, except when something is very expensive and then we must ask the Board of Directors.’ EIRT is governed by an independent board composed of lawyers, businessmen and two government members.

Ί ‘m not the only boss. If I were, I have seen enough in these past months to know what should be done. Unfortunately the organization of EIRT is such that decisions are not made quickly enough … sometimes weeks pass before action can be taken. Thus I am always waiting for decisions to be made.’

In the absence of studies or surveys it is very difficult to measure, however, the reaction of the viewing public to the new programs. Televised versions of Shakespeare’s plays with Greek subtitles may have no meaning for villagers, it has been argued. ‘We ought to have a surveying service to do such work but we don’t,’ Solomos explained. ‘We need many things. We need studios and trained personnel. We have some people who are very good collaborators and have good ideas, but wherever there is bureaucracy, I am completely unable to get things done. My freedom is very limited. That’s why I’m not responsible for the mistakes that are made here. I haven’t hired the people at EIRT, for example… I’m not too happy with the job as it now exists. I ought to have a dictators’ power,’ he added jokingly, ‘and then we would move much faster.’

Nonetheless, that something new is stirring at EIRT is evidenced in the recent series based on Kazantzakis’ The Greek Passion (Christ Recrucified), generally regarded as iconoclastic by the Orthodox Church which in 1954 declared it to be unsuitable reading for members of the faith. In a recent article in Tahidromos, Eleni Kazantzakis, the author’s widow, expressed her pleasure that the book, so unjustly criticized, is at last being seen by all Greeks, and commented favourably on Solomos’s endeavours. ‘The decision was a just and great step forward for Greek television,’ she said. This is equally true of all the developments at EIRT.

The man who is largely responsible for these changes brought with him to EIRT a formidable background in the theatre and it is for his work in drama that Alexis Solomos is best known here and abroad. A versatile director, he is equally at home in ancient and modern plays, tragedy and comedy; he has stubbornly refused to limit himself to one school, period or kind of drama.

When Constantine Karamanlis asked Alexis Solomos to accept a position at the National Radio and Television Network of Greece, the actor, designer, scholar, and director replied, ‘Mr. Prime Minister, I think you are throwing me into the Amazon to swim among the alligators while the natives are shooting me with poison arrows from both sides of the river bank.’

Solomos first became involved with theatre as a student at Athens College. Karolos Koun, director of the well-known Theatro Tehnis, was then teaching English at the well-known private school and encouraged Solomos and his fellow students to participate in theatrical productions. Solomos later joined an acting company in Athens but eventually set off for England to study at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts in London where he directed his first play in 1946, an all-student production of Aristophanes’ The Assembly of Women (Ecclesiazusae). Solomos then crossed the Atlantic to study at the Yale School of Drama and in New York at the Dramatic Workshop under Erwin Piscator whose concept of ‘epic’ theatre had such a profound effect on a previous student, Bertolt Brecht. Solomos directed several plays at New York’s Cherry Lane and other Off-Broadway theatres before returning to England to teach at the Royal Academy.

WHEN Solomos eventually resettled in Greece, he established himself as an independent director and producer. He worked with the National Theatre from 1950 to 1964 and later formed his own company, Proscenium. In addition to directing and producing plays, Solomos has written on many facets of the theatre. He has published studies on Christian tragedy (St. Bacchus), ancient Greek tragedy (What about Dionysos?) and Cretan theatre. He has also written a collection of essays on the history of drama (The Age of the Theatre), and a book on comic theory is currently in progress. The Living Aristophanes is an important contribution to the critical tradition of comedy. In the introduction to this book (published by the University of Michigan Press in 1974), he wrote: ‘What must be faithfully revived in contemporary productions is not the aspect, but the spirit; not a picture, but a vision.’

It is a ‘living’ Aristophanes that Solomos has presented to Greece and the world for almost thirty years. In his production of The Frogsmuch is done to give the play a contemporary flavour. Euripides appears on stage riding a motorcycle, Dionysos enters Hades in a brightly-painted fishing boat, bouzouki music is played at a taverna, and the chorus of frogs, outfitted with swimming flippers, waddles around the stage to music by the popular contemporary composer, Manos Hadzidakis (perhaps best known abroad for his music to Never On Sunday).

Adding a contemporary flavour to classical plays, however, may sometimes create other problems. In 1966 Solomos directed several productions of Greek drama at the University of Michigan. When planning Aristophanes’ The Birds, it was decided by all involved that Bert Lahr, the sour-faced old ham actor, was just the right man to bring Aristophanes to life for an American audience. It soon became apparent, however, that Aristophanes would have to bend to Lahr. Having won iame for such roles as the Cowardly Lion in the Wizard of Oz and Gogo in the first American production of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot in 1956, Lahr was then enjoying national popularity for a potato chip commercial he had done for American television. He considered it only reasonable that he munch his chips during the performance, and threatened to quit if he were not allowed to do so. Although Lahr’s attitude towards ancient drama was somewhat cavalier, his attitude towards matters of propriety was not. A puritanical man, he insisted on censoring many of Aristophanes’ great, bawdy lines. ‘What we produced’, Solomos playfully lamented, ‘was Aristophanes’ Serf rather than The Birds.’

Solomos has directed every Aristophanes play except Plutus, and has revived or revised many of these at least once. ‘It is difficult to breathe new life into an old production,’ he noted. Ά revival is a little bit like a faded woman you have been to bed with many times. The virginity and sense of adventure are gone!’

EIRT may not have been exactly virgin territory when Solomos arrived on the scene, but it has no doubt provided the director with many adventures. Alexis Solomos has nonetheless found the time to remain active in the theatre. In the past year he has directed Aristophanes’ Frogs and Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi for the National Theatre, translated and directed Brecht’s Drums in the Night at the Kappa Theatre, and overseen four productions for the summer festivals: Aristophanes’ Lysistrata and Euripides’ Trojan Women which were presented at Epidaurus in July, Aristophanes’ The Clouds and a modern Greek drama, Lazarus by Pandelis Prevelakis, which will be staged this month at the Odion of Herodes Atticus and Sophocles’ Antigone, scheduled for September. As to his post at EIRT, Solomos says, Ί am here only as long as the government needs me. I care for this work, but I can’t think I will be here always.’

Perhaps when the prolific actor, designer, scholar and director retires from television, he will add yet another book to his collection, a story about his experiences at EIRT. He may well call it Ά Kafkaesque Fairy Tale’.