TRAGEDIES by Sophocles and Euripides and comedies by Aristophanes are being reenacted this summer at the giant ancient amphitheatre of Epidaurus. Hewn out of the mountains among tall pine trees by the architect and sculptor Polycleitus the Younger in the Fourth Century B.C., the theatre, with its fifty-five tiers seating about 14,000 spectators, is one of the best designed and preserved ancient Greek constructions. Its marvellous acoustics always delight visitors. The dropping of a coin on a marble slab in the centre of the orchestra, the rustle of the actors’ costumes and even their whispers are clearly audible on the uppermost tiers.

The Epidaurus Festival of ancient drama was inaugurated in 1954, principally to entertain a boatload of European royalty (enthroned as well as dethroned) then cruising in Greek waters. Organized since then for more plebeian audiences, it has provided a wonderful opportunity for the revival of ancient plays in their antique natural setting, at the very theatre where ancient audiences also witnessed them, not far from the kingdoms of Mycenae and Argos whose tales ancient dramatists often recount.

The plays, of course, are now performed in modern Greek to the accompaniment of tape-recorded music. Making a play appeal to an audience more than two thousand years after it was written is a difficult undertaking, indeed, and the thrill felt by audiences in our day is evidence of the success of Greek theatrical directors in reviving the literary treasures of bygone days. It appears to be much more difficult to revive an ancient comedy than an ancient tragedy. The latter usually tells a story with an ageless message understood by people practically everywhere, whereas comedies usually carry messages based on ephemeral and topical humour not grasped by people at other times or places. Hence the changes, arrangements and compromises to which modern producers and directors sometimes resort in order to make ancient comedies truly entertaining. Karolos Koun’s production of Aristophanes’ The Birds (not The Chickens, as most modern Greeks like to think) has been one of the most successful and delightful achievements in this field, hailed in many countries where it was performed — even though it raised eyebrows and controversy when it was first performed in Athens. The techniques used by ancient dramatists, with the vital role of the chorus, the high emotionalism involved in acting, the appearance of a deus ex machina, etc., combined with the architectural design of amphitheatres, probably created greater participation of the audience and thus brought about better communication of the author’s message than modern dramatists can hope to achieve. The distinction between the so-called real world and the world of the imagination was probably less clear in an ancient theatre than on the more sophisticated modern stage where the curtain symbolizes a sharp boundary between the two worlds. According to Plutarch, Solon the . legislator is said to have scolded Thespis the actor for telling so many ‘lies’ in front of so many people. But great dramatists and actors often succeed in making audiences wonder whether the world presented to them on stage might not be more real — by bringing out into the open their innermost thoughts and feelings — than the shabby lives they lead in day-to-day hypocrisy.

After all, precisely on account of this blend of the worlds of the imagination and real life, ancient drama constitutes one of the most complete and effective communications media, combining prose, poetry, music, singing, dancing and appropriate gestures, often by many actors at the same time, affecting emotions and intellect alike. Drama, at some very early date, must have sprung out of ancient religious ceremonies, with incantations, sacrifices and the reenactment of legends about deities. Religion played a dominant role in practically all aspects of ancient life, and this was inevitably reflected in the development of drama.

Hurried visitors to and from the Epidaurus theatre usually bypass without a second look the nearby ruins of the Asclepieion, where the true everyday life drama actually took place in ancient times. The Asclepieion was perhaps antiquity’s most famous combination of faith-healing shrine and fully-equipped hospital (a sort of Lourdes and Mayo Clinic put together) and, at least for those with a trained eye for archaeology, it is still one of the most fascinating historical sites in Greece.

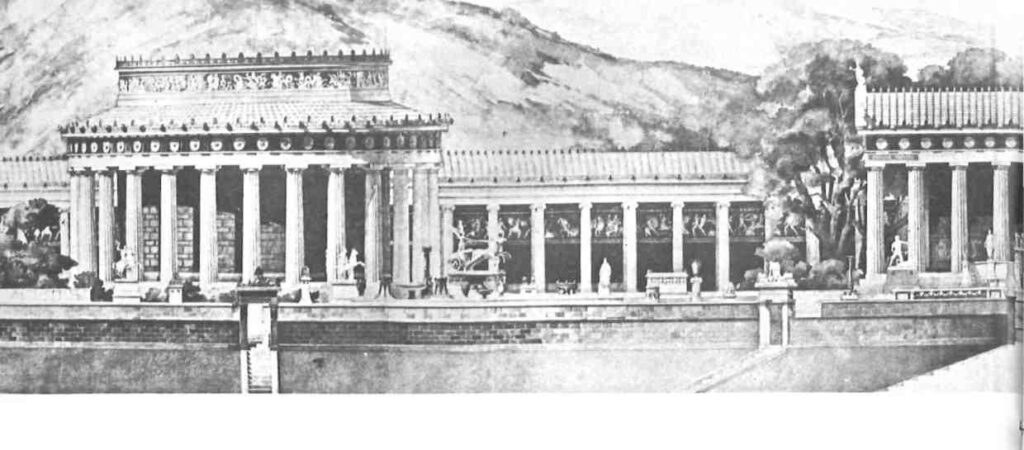

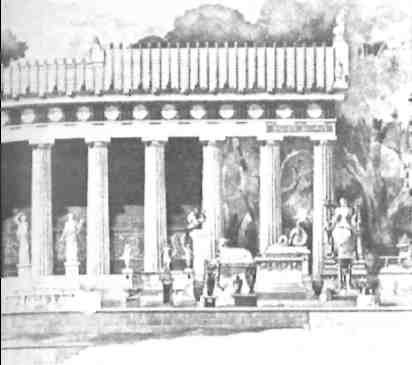

The shrine was dedicated to the cult of Asclepios (or Aesculapius), god of healing. According to legend, a princess named Coronis was seduced by Apollo, gave birth to Asclepios in secret and exposed the child on a mountain near Epidaurus, where it was suckled by a goat and guarded by a sheep dog. In time, the word spread around that the site possessed the virtue of healing the sick. A shrine to Asclepios was built at an unknown date many centuries before Christ, and to this a sanatorium and thermal baths were later added. The whole place became fabulously wealthy thanks to the many offerings which those who were cured made to the shrine. To make the sojourn of the sick more agreeable, a stadium, a gymnasium and a concert hall were built in the Fifth Century B.C. and the giant theatre a century later.

The story of the Asclepieion is in a sense the story of medicine itself — an admirable blend of religion, magic and science. In the first place, the site was well selected for its pure and invigorating air, calm surroundings, rich vegetation and mineral water springs. Thus, drinking pure water and observing a diet of health foods in a pollution-free atmosphere were obviously a vital part of the treatment. But the physician-priests who ran the sanatorium-shrine placed faith-healing high in importance among their cure-all techniques. After attending a series of religious ceremonies, the patient was required to spend a night in the temple where Asclepios in person was expected to visit him in his dream. The following morning the patient would recount his dream to the priests, who — combining the qualifications of Dr. Freud and Dr. Kildare — would interpret it and prescribe the appropriate treatment.

That was the first stage in the treatment and it might have sufficed for easy cases. For more complicated ones, the patient — not necessarily a mental case — was required to spend another night on the premises, this time in a dark snake pit under the Tholos. As a rule, this shock treatment was enough to drive patients back into their wits. The snakes would apparently lick the patients’ bodies or wounds; this was regarded as extremely effective treatment. The snakes used were a harmless variety abounding in the area. Known appropriately as Aesculapian snakes, they were smooth, glossy and slender, uniformly yellow to brownish in colour, with a streak of darker colour behind the eyes. Allegorically they were said to symbolize self-revival.

The snake-pit technique was traditionally the highlight of treatment at the Asclepieion. In fact, the snake, wound around a staff, was Asclepios’ trademark, and physicians now display it on their automobile windshields in the hope of avoiding an illegal parking ticket.

Thus psychosomatic medicine is not a. modern discovery, as many people think. It was known and practised long before medicine — and human knowledge in general, for that matter — was departmentalized into a lot of specialties, with surgeons uninterested in the findings of psychiatrists, cardiologists ignoring the work of ophthalmologists, and so on. Basically, of course, the physician-priests of the Asclepieion relied for their healing techniques on suggestion and the religious faith of their patients. Presumably if the prescribed treatment failed to work, it could all be blamed on the patient’s lack of faith in Asclepios. This was a distinct advantage which the Asclepieion medical men had over their modern counterparts. Nowadays such faith is lacking, even though a lot of it is still required in order to be cured in some modern hospitals — especially when the patient presents his health insurance card.

To help Asclepios in his miraculous cures, the priests also prescribed more practical treatment, using a great variety of locally grown herbs — the raw material for most modern drugstore prescriptions. It appears that the Asclepieion priests were familiar with many therapeutic as well as anaesthetic plants. The climax in the story of medicine came when they actually developed and used surgical instruments as well. Scores of needles, forceps and even syringes have been unearthed among the ruins.

One story tells of an ancient monarch who wrote to the temple giving a long list of ills from which he was suffering and asking whether the god Asclepios could cure him. The priests, who studied his complaints carefully, invited him to come along, but on condition that he came on foot, slept in the open and ate only fruits and vegetables. The king — who probably needed to eat less and exercise more — followed the advice and was cured of all his ills by the time he arrived at Epidaurus. Naturally he attributed his cure to the god and showered the temple with offerings. In fact, the fame and magic spell of the Asclepieion were so great that on many an occasion it was said of a patient that ‘he arrived and was instantly cured’ — even before going through the classical snake-pit (or perhaps in fear of it).

The local museum contains several inscriptions recounting in detail how paralysis, blindness, sterility, fractures or dislocations were miraculously cured. There is one tablet that an optimistic patient named Diophantes thought fit to draw up even before he was cured. A remarkable example of faith, the tablet reads as follows; Ό Blessed Asclepios! It is thanks to thy skill that Diophantes hopes to be relieved from horrible gout, no longer to move like a crab, no longer to walk upon thorns, but to have a sound foot as thou hast decreed.’ We have no record of Diophantes’ post-therapy condition.

Little is now left among the grass-covered ruins of the once famous Asclepieion to impress the visitors. Only the giant theatre — which incidentally was built in such a way as to enable the audience to face the magnificent buildings of the sanctuary in the distance — will go on thrilling spectators for many more-years to come. The size of this theatre makes visitors (mindful of the lack of hotel rooms in the neighbourhood and heavy motor traffic to and from Epidaurus) wonder how it was filled with spectators in ancient times, where these spectators came from and how they were housed and fed between performances. It goes to prove, however, that an immense number of people actually visited the Asclepieion for treatment. Another mystery is whether the plays performed at the Epidaurus theatre in ancient times were regarded by the Asclepieion physician-priests as being merely a sideline entertainment for patients or as an integral part of the therapeutic process. If modern producers-directors-actors can solve this mystery, perhaps they will learn the secret of how to perform before fewer empty theatre seats in the future.