The Corfu Reading Society

Many people believe that the University of Athens, founded in 1837, is the oldest cultural institution in Greece, but this is not so. There are several that are older in Corfu alone, and the Corfu Reading Society is one of them.

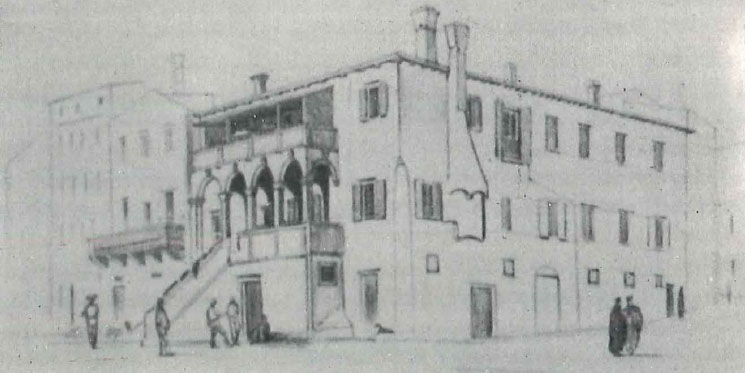

Located in a handsome house of the Venetian period, the Society lies opposite the west front of the Palace of Saint Michael and Saint George, said by some to be the finest Regency building outside of Britain. An open staircase on the facade leads to a stone-arched loggia where the entrance gives into a hallway, off which are several of the Society’s seven principal rooms.

The Reading Room contains volumes of reference and magazines, mainly in French, English, German and Greek. On the walls hang portraits of notable Corfiots, among the earliest being Nikoforos Theotokis and Evgenios Voiilgaris, the two leading figures of the Greek Enlightenment. Among portraits of living members, there is one of Mr George Rallis, who was prime minister a decade ago.

Off the Reading Room is the Library which contains most of the Society’s 30,000 volumes. Among the bound copies of literary magazines, the Revue des Deux Mondes stand out prominently in their stout red covers. The Corfu Reading Society is the oldest continuous subscriber of this review outside France, having not missed an issue from 1836 to the present.

From here, the usually barred doors may at times be ceremoniously and solemnly opened, leading into the Ionian Room which includes the John Capodistria Museum. Said to be the most prominent figure produced by the Ionian Islands since Odysseus, the Corfiot count was born in 1776, studied medicine (and founded the country’s most venerable medical association), rose high in the diplomatic service of Tsar Alexander I and was the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs at the Congress of Vienna. Probably his chief contribution to European political affairs, however, was the drafting of the first Constitution of the Helvetian Confederation.

What Capodistria succeeded in doing amongst the Swiss, he failed to accomplish with his own people. While president of the first provisional government of independent Greece, he was assassinated in Nauplia by members of the fierce Mavromichalis clan who were personally opposed to some of his policies. Ironically, Capodistria was struck down at the entrance to the Church of Saint Spyridon, the patron saint of his homeland. One of the treasured memorials of the great man, a gold box which stands on his desk, is a gift from the grateful cantons of Switzerland.

The Ionian Room contains several thousand precious volumes by native authors. This collection is continually being enriched, and people from all over Europe come here to research the history and culture of the Seven Islands.

If the first floor of the Society is devoted to the written word, the second is decidedly dedicated to the oral. Here is the card room, the sitting room and the bar. There is also a lecture and music room outfitted with comfortable chairs and a grand piano.

The premises as a whole is redolent of Corfu’s past and much of it is devoted to the days when the nobility flourished. Among the possessions of the Society is a copy of the Libro d’Oro – the original was publicly burned during the Napoleonic occupation which lists the names, arms and privileges of those whom the Serene Republic endowed with titles. Each of the Ionian Islands had its own, and it was a central pillar on which the structure of society was secured.

The landed aristocracy was built along western lines and almost all the titles were conferred by Venice. The sons of these families mostly attended the University of Padua where they became familiar with the classics, Renaissance art and literature, and western science. They enjoyed Italian theatre, opera and concerts; they spoke the Venetian dialect, but they remained uncompromisingly Orthodox in their faith. Even the noble families which migrated from Venice – the Dellaportas, Momferratos, Typaldos, Marchettis – were converted, through intermarriage, to the Greek Church.

Nevertheless, the foundation of the Society itself reflects the clear, fresh breeze of liberalism that first stirred this stagnant Venetian backwater two centuries ago. A small group of Corfiots studying in France picked up the ideas of the Enlightenment, which were fired by the nationalism that burst forth with the American and the French Revolutions.

The extinction of the Venetian Republic by the forces of Napoleon and the subsequent occupation of the Seven Islands by troops of the French Republic, were greeted with enthusiasm by the people, and the Libro d’Oro of the aristocracy was burned.

Soon, however, the excesses of the Terror, the discomfit of the aristocracy and the Church’s fear of republican atheism, brought a reaction. against liberalism which lasted for more than a generation. But, with the advent of the British and a period of good relations between them and the people, a new era of progressive liberalism arrived. Stimulated by a love of thought and literature and animated social intercourse, a group of young, middle class Corfiots, led by Petros Vaflas Armenis, founded the Society in 1836.

The British cultivated the goodwill of the aristocracy mainly by instituting the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, but they also invited its members to join them in quadrilles and paper-chases and, feeling positively enclined, the Corfiots picked up the amiable English habits of playing cricket, drinking ginger beer and building country estates. As time passed, the liberalism which the British introduced came to mean nationalism for most lonians, particularly after the upheavals of 1848 in Europe. Vailas, long president of the Society, became an supporter of enosis, and when union with Greece was realized in 1864, for his efforts he was awarded the post of ambassador to Paris, then to Saint Petersburg, and finally to London where he died in 1884.

Over a century later, the Society continues to flourish. With a grant offered by President Karamanlis a few years ago, the Ionian Room was able to acquire the archives of Lord Guilford, the great philhellene who played such an important role in the cultural life of the Ionian Islanders during the first quarter of the 19th century.

The Society has also been able to take advantage of the talents of the distinguished architect John Kollas, a member who had superbly restored the Palace of Saint Michael and Saint George in the mid-1950s. One project has been the restoration of the Flanginis mansion and its chapel. The first great Greek benefactor of modern times, Thomas Flanginis, barred legally by the Venetians from opening a boy’s school in Corfu, founded one in the centre of Venice itself in the 17th century. Today the Palazzo Flangini, designed by Longhena, houses the Hellenic Institute for Post-Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies next to San Giorgio dei Greci.

In its more than 150 years of history, the Corfu Reading Society has seen many changes, but in its fervent striving to preserve the history of the Ionian Islands and to encourage Greece’s current and future cultural achievements, it attracts a growing number of distinguished visitors every year. Today its social prestige has been surpassed by a cultural one – the best kind.