Young Greeks who attend the American Farm School are marked for life. “It’s not just the free tuition and the skills they learn,” says Ford tractor distributor Paul Condellis of Athens. “These can be learned elsewhere. It’s the character-building, the formation of the wonderful character of the school graduate. I find this a hundred times more interesting and important than the skill-training.”

Mr Condellis is a vice-chairman of the board of trustees of the Thessaloniki Agricultural and Industrial Institute as the Farm School is officially called. He first became aware of the the character of its graduates while establishing the agricultural machinery division of the family business.

Mr Condellis’ father spent the World War I years in the United States working at the Ford Motor Company. He returned to his native Lesbos in 1918, driving the first motor car to be seen there and obtained the Ford dealership in Greece the following year.

Young Condellis travelled the length and breadth of Greece throughout the 1950s and 1960s selling Ford tractors to Greek farmers as a replacement for ox-drawn ploughs. He recalls being repeatedly impressed by certain farmers who stood head and shoulders above the rest. “Going round the villages, sitting at coffee shops over ouzo, I kept noticing these farmers who knew far more than the others. They could analyse their needs and would be able to say exactly what sort of tractor they wanted,” he says. At first he accepted this as some sort of phenomenon. Then he began to wonder where they learned what they knew. Talking to one after another, he discovered that they had all been to the Farm School.

One of his agents once sought special terms for a would-be customer. “No way: rules are rules,” Condellis told the man. “Then came the magic words: ‘He’s been to the American Farm School.’ Without a second thought, I said ΌΚ’. I immediately had complete confidence the deal would be honored. It was then I decided it was about time I visited the place.”

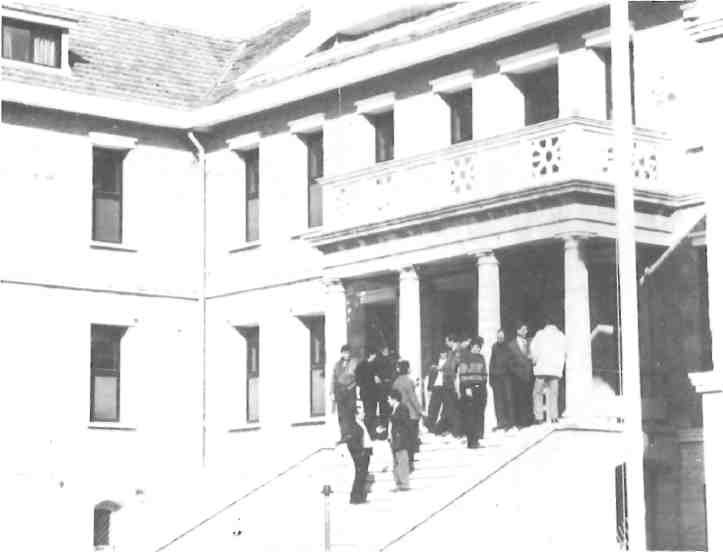

So he made the trip to Thessaloniki. Lying just south of the city between Mount Hortiatis and the Thermaic Gulf, with a view to Mount Olympus in clear weather, the school is set on an 375-acre tract. The founder, John Henry House, bought the original 50 acres of nearly desolate wasteland early this century. He reasoned that since much of the surrounding farmland was unpromising, boys should learn to farm successfully on the worst possible land. Mr Condellis met the director, then Bruce Lansdale, and began his active, twenty-year association with the school. He has seen a gratifying increase in Greek sponsorship of students, now numbering 220 a year.

Ford and Condellis have donated several tractors and other agricultural machinery to the school over the years. A major Ford contribution has been $50,000 worth of computer equipment, so every student learns basic computer skills. A visiting deputy-minister of agriculture was astonished. “What do they use computers for?” he asked a 17-year-old boy at a keyboard. “I’m preparing a feeding program for my father’s cows,” the boy answered. “How long has it taken you to learn?” the minister asked. (It was December.) “I came in September,” said the boy. “You had a computer at home?” “Only a television,” he replied.

To Mr Condellis it is axiomatic that farm managers of the future are computer literate. “In 25 years a farmer who cannot use a computer will be like the old-time illiterate peasant who could only put a cross beside his name,” he says. He takes pride in his company’s assistance to the Farm School’s move to computerize Greek agriculture.

A critical problem for the school today is a decrease in donations from the United States. “It’s a question of need,” comments Mr Condellis. “Boys coming to the school no longer have patches on the patches on their pants. They don’t need to have their hair cut and deloused any more, as village boys used to. They don’t have just one pair of shoes and those not looking as if they’d last the year… Now they have all they need.”

But the school still gives a singular sort of education, he believes. “It manages to turn village boys and girls into farsighted, thinking farmers, able to analyse their needs logically. It is this sort of education that is important, not a matter of turning out PhDs, but of producing people with good brains who can think for themselves,” he says.

In his view, the achievement stems from the combination of boarding and communal living, with a dedicated resi dent staff, where students realize they are valuable as individuals. “Can you imagine what it means to a village kid to stand up in front of morning assembly and give a talk? They understand from having to do it that they are important, and learn to do it naturally.”

“Then there’s some religion, just enough to make them interested: a nice, good dose. And there are many other activities, dancing, music, athle¬tics. It all goes to improve them a little bit every day,” he says. To spread the benefits northward, Ford underwrites scholarships for two Albanian boys now at the school. Mr Condellis is also assisting the Farm School in a project supported by EC funds called AVATAR (Alliance for Vocational Agricultural Training in the Albanian Region).

Underlining the acute need, he cites a report he prepared for the European Commission comparing agriculture in Albania today with that in Greece 40 years ago. “Albania today has one tractor for every 2000 stremmata (500 acres). Greece had more than that in 1952 and now six times more.”

By the end of the 1980s, EC funding had become the main source of Farm School revenue, says the present director, George Draper. “All students are on scholarships, worth close to 1 million drachmas each a year. Most of our students come from rural families of modest means.” His wife Charlotte Draper adds, “They are hard-working people. We shake hard, calloused hands.”

EC Integrated Mediterranean Program funds are providing most of the financing for improvements to school laboratories, trade workshops and older buildings. The school must fund the balance, but EC funding will cease in a year or two, and with American sponsorship dwindling, Greek support has to be strengthened.

Fund-raising in Greece through groups in Athens and Thessaloniki has led to a trebling of private donations in the last six years, says Mr Draper, mostly from business and industry. The school now has 500 donors in Greece with an annual target of over 55 million drachmas compared to 50 donors and a five million drachma goal in 1977.

Leading the Athens development committee is school trustee George Legakis, of Helionic Corporation, who found the Farm School a worthy cause for Mobil Oil in the 1950s. As company public relations officer, he reviewed the budget for charitable donations and visited the school.

“The main thing we want is for people to go visit the school,” he says. “The school itself is the best sales weapon we have. No sales pitch is needed once people have seen the place. They go there. They fall into Charlotte’s hands. And the job is done,” Legakis says.

The dozen or so committee members meet monthly. “We’re low-profile fundraisers,” says Mr Legakis. “The policy is to focus on one sector at a time, banking, insurance, the food industry, and invite a couple of speakers from the area to give us advice on how to increase donations by offering incentives to companies to support the school.”

He cites the case of Gerasimos Vassilopoulos, of the Alpha Beta supermarket chain. “The school had sold products to Alpha Beta, like cheese and ice-cream in the days it was produced, but he had never paid a visit.” Scion of a rural Peloponnesian family and a shepherd himself till the age of ten, Mr Vassilopoulos instantly fell under the Farm School spell on his first visit.

The supermarket magnate now entertains committee members annually at his farm in Attica. A Legakis helicopter, flown by an evzone-costumed pilot, whirls down among the Vassilopoulos goats. “I’ve proved that helicopters and goats do mix,” says Mr Legakis.

“Our corporate donors support students and hope they’ll support us when they are running their own farms,” he says. This commitment reflects agreement with the school’s basic philosophy of encouraging young people from Greek villages to stay at home, rather than move to already overcrowded cities.

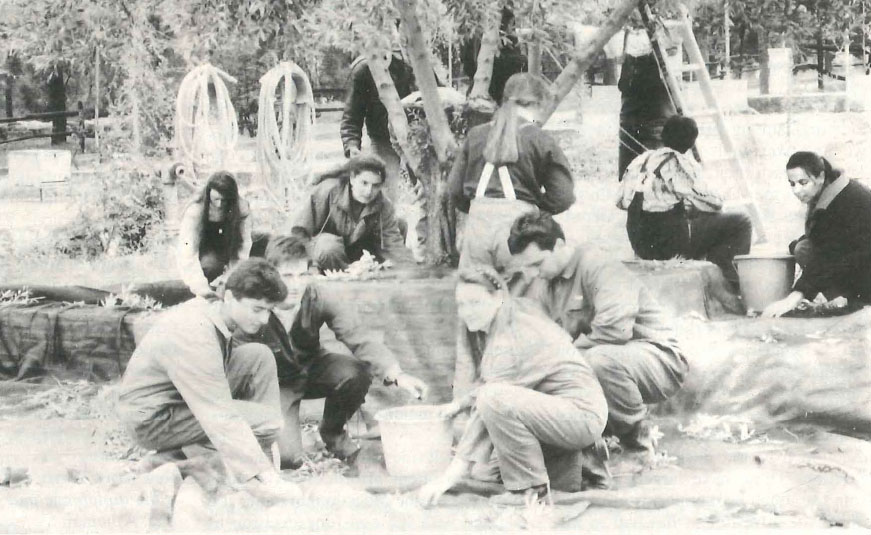

Elsa Kafantari from Theologou on Thasos, one of the 70 girls at the school this year, hopes to set up a greenhouse vegetable business on her island after graduation. “Thasos produces no vegetables. It has to import all from the mainland,” she says. She specialized in horticulture and learned to grow greenhouse vegetables in an organic gardening project. She sold the produce (tomatoes, aubergines, peppers, onions, garlic and lettuce) to residents on campus or visitors.

Elsa studied farm maintenance, mechanics, carpentry and drives a tractor. She has raised poultry; slaughtered and prepared chickens for the table; raised pigs, been midwife to a sow and cleaned pighouses. She has also raised turkeys from chicks and mastered the process of milking cows.

Nikos Soultoyiannis is from a Sarakatsani family in Kilkis. His father, a 1955 Farm School graduate, sold the family’s traditional flock of sheep in 1974 to free himself from constant animal care and switched to crop cultivation. “We have wheat, sugarbeet, corn and cotton and have recently begun producing seed oil,” says Nikos.

From observing his father, Nikos is clear about the benefits of farm school education. “My father gained a new vision from the school,” he says. “The training helps you look ahead in a way that other Greek farmers may be less likely to do. My father invests in new machinery each year and is the leading producer in the dozen or so villages in our area because of his modern drip irrigation system which gives higher yields.”

He has every expectation that he, like his father, will be at the forefront of modernization in Greek agriculture and will succeed as an independent grower. “Co-operatives have problems,” he says, “because the middle-aged, in general, only want to make money.”

Nikos’ father came back to the Farm School as a graduate to do a short course in computer technology and is now in the school’s computer network. This gives access to the latest data on agricultural developments and technology as well as the latest prices for produce in Europe.

Elsa Kafantari

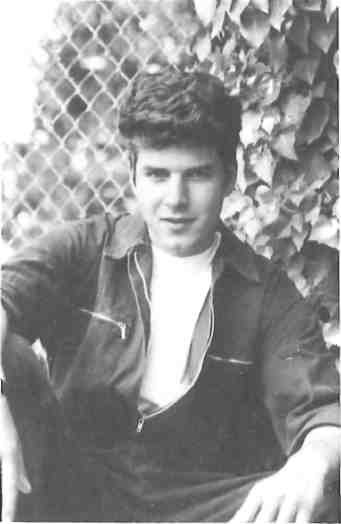

Nikos Soultoyiannis

Giorgos Panaghi

Pantelis Kavvas

Kyriakos Netkidis

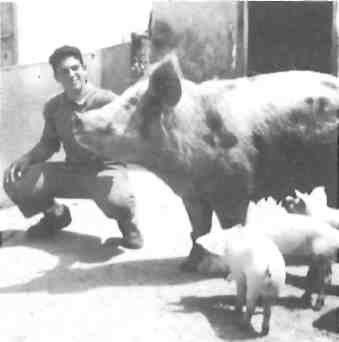

Giorgos Panaghi is from a pig farm near Larnaka in Cyprus where his father slaughters one hundred pigs a day. His aim, however, is to slaughter 50, and make the same income with animals twice as good. “The Farm School raises students’ awareness of the importance of quality,” he says. He values the broad agricultural training at the school, in comparison to others in Europe where students tend to specialize. He hopes to study meat technology in the United States.

Pantelis Kavvas is from a family running a pistachio plantation in Aghios Thomas, a village near Thebes. His father also does contract bulldozing. Pantelis’ interest is animal husbandry, his goal being to establish, with a loan from the Agricultural Bank of Greece, milking herds to supply the Athens market.

He appreciates the opportunity at the Farm School to learn to live cooperatively with his peers and work with advanced technology. He values the managerial techniques which he often finds lacking in smaller Greek villages where a conservative older generation makes the introduction of change a problem, especially for young people. “When the young go back to the village with know-how from the Farm School,” he says, “they can find the opposition to change hard to cope with.”

Kyriakos Netkidis from Langadas became acquainted with the Farm School from the time of his mother’s attendance at a short course on green-house horticulture at the Ministry of Agriculture centre on the campus. He plans to go into business partnership with her growing carnations, chrysanthemums and calendula for the market.

In a student pot-plant project, he grew irises and sold them for profit and has had experience striking cuttings of olive, peach and apple trees (90 percent successful), growing vegetables and bee-keeping. His computer training has been important he believes. “A computer is useful for organizing a green¬house , watering and assessing expenses,” he says.

For Kyriakos dancing has been an extra-curricular activity. Excellence in dancing at the Farm School has the sort of status which elsewhere is attached to prowess in sports. As a member of the feted Farm School dance troupe, whose repertoire specializes in Macedonian dances, Kyriakos visited Strasbourg last May to take part in European celebration for students of agricultural schools.