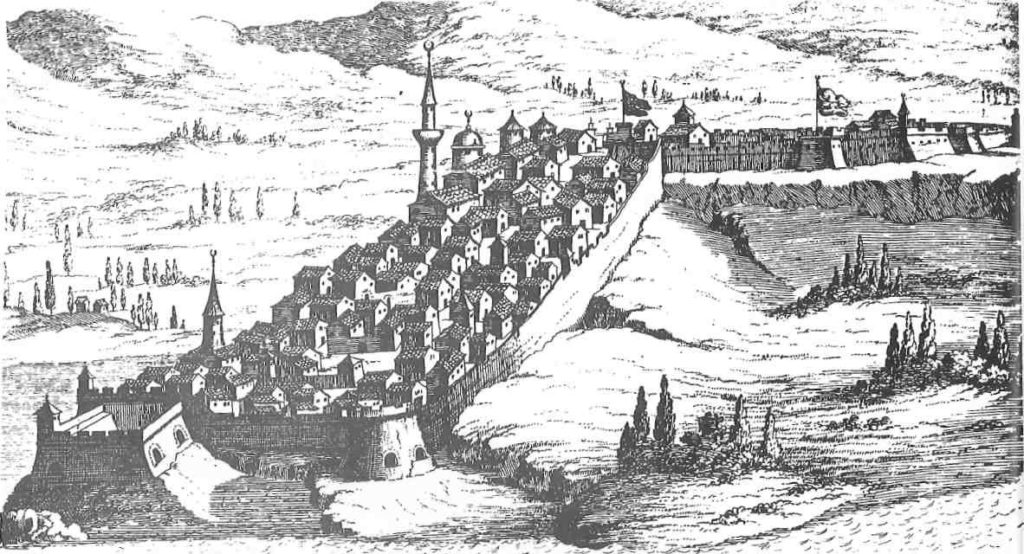

With Suda in Crete, Navarino Bay is the best and safest roadstead in the Eastern Mediterranean. Located on the south¬western coast of the Peloponnese it was known to Homer as “sandy Pylos”; in Frankish times as Porte de Jonc (Bay of Rushes), corrupted in Venetian times to Zonklon.

The name ‘Navarino’ is derived from the Avars who first appeared at the end of the sixth century and not, as is often erroneously assumed, from the Navarrese who raided here much later. This is a mere coincidence of sound. The Avars were a wild Turkic people who lorded it over the Slavs settled in the Balkans. They are said to have subjected the Peloponessus for over 200 years, until drivenout by the Byzantines after their unsuccessful siege of Constantinople in 804. The initial ‘N’was pinned in front of ‘Avarinon’, as the final letter of the preceeding article, eis ton Avarinon, hence ‘Navarino’. So ‘Istanbul’ comes from eis tin polin and medieval ‘Nio’ from Ios, ‘Natenes’ from Athens, etc.

At the northern end of the bay in the narrow channel of Sikia, stood the sea port ‘sandy Pylos’ whence Nestor in The Odyssey set sail for Troy. The ruins of dear old Nestor’s palace can be found about nine kilometers to the north, off the main road, on the hill of Englianos thanks to Carl Blegen’s discoveries, one of the foremost archaeological excavations of this century.

It was here that Telemachus stopped to ask information of Nestor about his father long after the Trojan war was over. In classical times the port of Pylos was the location of a signal Spartan defeat by the Athenians during the Peloponnesian war.

The ancient acropolis of Pylos, lying 130 metres above these still sandy shores on the heights of Koryphasium, became the foundation for the Frankish castle of Avarinos built by Nicholas II de St Omer for hisjiephew Nicholas III in the late 13th century.

Lying opposite the north end of Sphacteria, the five-kilometre-long precipitous island that affords this bay its protection, the castle played supporting rather than leading roles in the medieval history of the Morea. Here, in 1313, Marguerite de Villehardouin, daughter of Prince William, was held captive when she tried in vain to claim the principality for her daughter Isabelle; here, too, in the latter part of the same century that Maria de Bourbon tried to claim Achaia for her son.

In 1381 the castle passed from the Franks into the hands of the Navarrese Grand Company. The last Prince of Achaia sold it to the Venetians in 1423. Along with Methoni and Koroni it became one of the Venetians’ three maritime strongholds in the southwest Morca, a strategic spot at the joint which linked the Ionian Sea with the Republic’s possessions in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean.

When Sultan Bayezit II appeared in person at the seizure of Navarino’s sister fort of Methoni in a blood bath of massacre and enslavement, Navarino capitulated without a fight. That was in 1500.

Seventy years later the aging castle’s last active involvement took place when Don John of Austria bombarded it in a bid to wrench it from the Turks. Among his men was Cervantes, and it has often been thought the latter’s service in the Morea became the foundation for the merry martial exploits of Don Quixote.

Don John (and Cervantes) failed to win the castle, and a year later, the Turks completed the natural silting up process that had been going on for centuries by filling up the narrow channel of Sikia. This rendered the castle all but obsolete.

So in the same year, 1573, they constructed a new castle, ‘Neokastro’, an artillery fortress, located at the south end of the bay, which now controlled the only navigable entrance at the south end of Sphacteria.

Whereas Palaiokastro, the old castle, was a proud and soaring fort to be reckoned with, Neokastro was low, sprawling and unconvincing, suited more to the prison it eventually became. However, for today’s world, with its peace-loving tourists, Neokastro wins hands down over Palaiokastro as a place to visit.

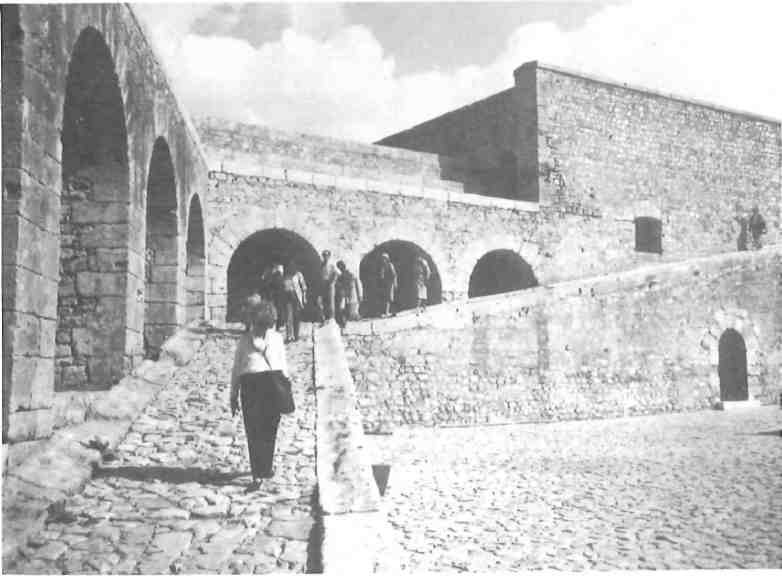

Hexagonal keep of Neokastro

Sloped passageway at Neokastro

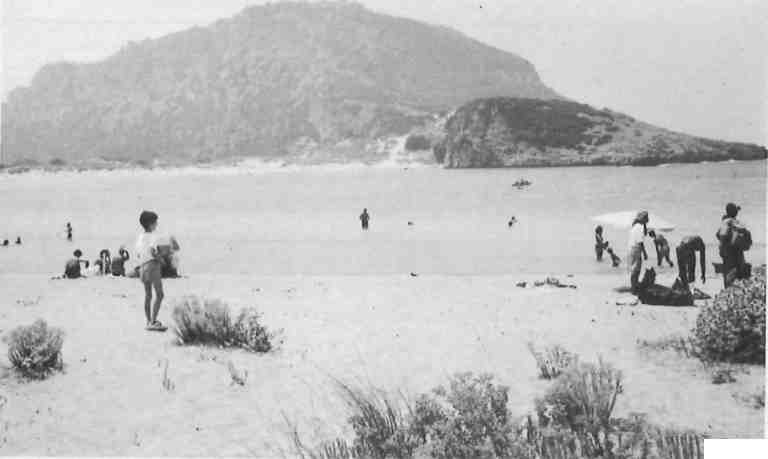

Palaiokastro lies brooding high upon the imposing pinnacle of Koryphasium, without benefit of even a sign to guide the would-be visitor up a track to its location, daring all but the professional hiker to storm her slopes and expose the secrets of her ancient stones.

Nor is it a climb for a sultry day, especially when the cool, blue waters of the circular cove of Voidokoila near its foot, with its soft, high dunes entice -Homer’s sandy world brought refreshing to life.

Neokastro, however, seven kilometers to the south, is one of the best preserved castles in Greece. It is such an amiable place today that park benches throughout the grounds under shady trees are placed in view of the southern end of Sphacteria and the natural arch of Tsichli-Baba. Here, legend has it, if a pregnant woman rides through the arch on a boat, her unborn baby will be a boy.

Pine trees planted by the school children of Pylos in 1926 now shade the entrance to the castle which is located just above the main square of the modern town laid out by General Maison in 1828.

Beyond the unpretentious entrance of the castle, immediately on the left, are the Maison Barracks, a long stone building with brown shuttered windows.,It housed the French troops until the castle was ‘liberated’ by the Greeks who turned it into a prison in 1830. So it remained until 1957 except for a few years during World War II when it was occupied by the Italians. In 1984 refurbishing began, and today it is being readied to house an important Marine Antiquities Museum.

The keep, located a short stroll up a stone path lined with fragrant laurel and geraniums, is reached through an arched entrance way. Light and clean and airy, it is hard to imagine that this hexagonal bastion as having once been sombre, or other than what it appears today, with its exquisite views over the bay.

But although the castle’s early history is comparatively skimpy, mainly telling of the struggle between the Turks and the Venetians, it did come into prominence for a few months in 1770, when it was under the control of General Orloff. This was during a disastrous episode when Russia, in its innumerable wars with the Turks, sought to rouse the Peloponnesians to insurrection. This was quite easily done, so desperately did natives want freedom from the Turks who sapped their land of its resources. But Orloff received other orders and sailed away, leaving the Greek population of Navarino Bay behind to pay the heavy price of Turkish vengeance.

It had one good outcome, however. Taking pity on the Greeks she had abandoned, Catherine the Great, in agreement with the Turks, transported the most destitute refugees from the Morea and resettled them on the Black Sea where they contributed greatly in founding the great trade city of Odessa.

There, a century and a half later, the plans of the 1821 Greek Rebellion were first hatched and reached their final flowering in that glorious event for which the glory of Navarino Bay is forever remembered.

Just 165 years ago, on October 20,1827, the allied squadrons of the English, Russian, and French sank the whole Turkish-Egyptian fleet, assuring the freedom of Greece.

Memorials to heroes, philhellenes of a multitude of nationalities, are to be found among the islands and along the coasts that surrounds the bay. It was the world’s last major sea battle to be fought with wooden sailing ships, and on windless days when it is perfectly calm, the sunken,, rotting hulls can still be seen lying in the dark shadows of the deep waters off Sphakteria. They are a silent reminder of the cost of liberty.

NICHOLAS-JOSEPH MAISON

One of the chief charms of Navarino Bay is the little town of Pylos itself, with its Square of the Three Admirals, huge plane trees and pretty arcades. Its cafes and air of civilized bonhomerie still betray their strongly Gallic origins.

The French presence in this part of world lasted only two years (1828-30) but it has left its mark both here and at Methoni with its own castle and French colonial town, a few kilometres south. Their sojourn is unjustly forgotten or put in a footnote.

After Admirals Codrington,De Rigny and Heyden made their spectacular contribution to the Greek War of Independence, England and Russia had a falling out, leaving the French to clean up the anarchic mess left at a time when Greece at last was free, but too war-weary even to control the land she had won.

Although the Egyptian-Turkish fleet had been sunk, the forces of Ibrahim Pasha were still in control (or running out of control), in the Western Peloponnese. France’s offer to intervene was accepted by the Great Powers and General Maison was dispatched there with an army of 14,000 men, landing in August 1928.

Garneray’s “Battle of Navarino” with Neokastro on the right (National Historical Museum)

General Maison is not as appreciated as he should be. One of the first of Napoleon’s generals to embrace Louis XVIIFs restoration, he is not much liked by the Bonapartists, and the Bourbons had their own favorites. It might therefore be fairest to his memory to quote the impressions of the Scottish historian, George Finlay: “The convention required the imposing force of the French general to compel Ibrahim to sign a new convention for the immediate evacuation of the Morea.

The convention was signed on the 7th of September 1828, and the first division of the Egyptian army, consisting of five thousand five hundred men, sailed from Navarin on the 16th. Ibrahim Pasha sailed with the remainder on the 5th October; but he refused to deliver up the fortresses to the French, alleging that he had found them occupied by Turkish garrisons on his arrival in Greece, and that it was his duty to leave them in the hands of the sultan’s officers.

After Ibrahim’s departure, the Turks refused to surrender the fortresses, and General Maison indulged their pride by allowing them to close the gates. The French troops then planted their ladders, scaled the walls, and opened the gates without any opposition. In this way Navarin, Modon, and Coron fell into the hands of the French.

“France thus gained the honour of delivering Greece from the last of her conquerors, and she increased the debt of gratitude due by the Greeks by the ad mirable conduct of the French soldiers. The fortresses surrendered by the Turks were in a ruinous condition, and the streets were encumbered with filth accumulated during seven years. All within the walls was a mass of putridity. Malignant fevers and plague were endemic, and had every year carried off numbers of the garrisons. The French troops transformed themselves into an army of pioneers; and these pestilential medieval castles were converted into habitable towns. The principal buildings were repaired, the fortifications improved, the ditches of Modon were purified, and a road for wheeled carriages formed from Modon to Navarin. Hie activity of the French troops exhibited how an army raised by conscription ought to be employed in time of peace, in order to prevent the labour of the men from being lost to their country. But like most lessons that inculcated order and system, the lesson was not studied by the rulers of Greece.”

With two castles on the Bay of Navarino, often confused with one another, and the Palace of Nestor’s ksandy Pylos’ nowheres near Pylos, why is the new town of Pylos not near old Pylos either?

This is due to General Maison. When he gently moved the inhabitants of the area who lived like vermin within the walls of Neokastro into the pretty airy seaside town which his soldiers had built for them, he called the place Pylos because he was a great lover of Homer. He was a brave military man, and a dedicated classicist, but his geography wasn’t very good. That’s why things are a bit bouleverse in today’s names around Navarino Bay.