Warrior bands on horseback penetrated into what is now Macedonia before 2000 BC, leaving “horse bones and the cord pottery of the steppe,” writes the historian A.R. Burn. Others followed. And throughout the next millennium, these Proto-Hellenic tribal units crossed the Pindus mountains while others, the majority probably, made their way south through the fertile valleys, forests and bogland of Macedonia following age-old routes along Axios, Strymon and Nestos rivers. These Indo-European Hellenic warriors were hunters and herdsmen who had early on domesticated the horse and the dog. In Macedonia, as elsewhere in Greece, they came to dominate the local folk who either fled, were slaughtered or assimilated.

According to Herodotus, these tribes shared common bonds of blood, language (a distinctive early form of Greek), customs and religion. The soaring majesty of Mount Olympus so impressed them that they made it the home of their gods, then later built their sacred town of Dion in its shadow. When they reached the sea it was for the first time: their language had no word for it. Some settled in Macedonia. Most moved on to the southern parts of Greece where the climate was more favorable and the indigenous populations more advanced, to create the Mycenaean dynasties. No major site from this period has yet been found in Macedonia, but there must have been active mutual trade for Mycenaean pottery has been discovered at coastal sites and as far inland as Kozani.

The mythical and early kings of Macedonia appear to postdate the arrival of the Dorians whose three main clans were led by the Heraclids, earlier Greeks claiming ancestry from the legendary Heracles. After much wandering, the Dorians, according to historian Nicholas Hammond, made their way down into the Peloponnese and other parts of Greece via western Macedonia. From the beginning of this period, there appear to have been close family links between the Dorian rulers of Argos in the Peloponnese and the kings of Macedonia, since Temenos, the Dorian founder of the dynasty in Argos, was believed to be the founder of the Macedonian dynasty as well.

According to Herodotus, Perdiccas, son of Temenos, together with two brothers, was exiled from Argos and fled north, first to Illyria and then made their way into Greek-speaking lands in Macedonia, eventually settling near Mount Vermion at the so-called Gardens of Midas where, according to Herodotus, “…roses grow wild…sweeter smelling than any others in the world.” From there Perdiccas conquered most of the country which was probably made up of a patchwork of small related communities.

Many modern historians agree that sometime during the seventh century, Hellenic tribes calling themselves Macedon, a name linked with ‘high’ in Homeric Greek, moved from the Pieran mountains and other uplands, to dominate the plains, thus giving their name to the whole country lying between Thessaly and Thrace. In his time, a lingual dichotomy appears to have existed between the Dorian speech of the court and the broad, Aeolic Greek which was spoken by much of the population.

About his successor Argeus little is known except that he appears to have had links with Dorian Corinth, since it then founded a northern trading colony, Potidaea, in Chalcidice. In the next century, Amyntas I must have been a ruler of some influence. When the all-powerful Darius, King of the Persians, planned his conquest of Greek territories, he sent the “seven most distinguished Persians in the army after himself” to demand Macedonian submission. Cautious Amyntas, realizing he could do little against the enemy hordes threatening his frontiers, proffered the traditional earth and water of submission and entertained the emissaries to a great dinner.

Herodotus colorfully describes the scene when the drunken Persians dishonored the court by demanding the , company and sexual favors of the royal Macedonian ladies. So enraged was Amyntas’ eldest son, Alexander, that he sent his old father to bed and had the visitors together with all their train murdered. To hush up this act he gave his sister Gygaea in marriage to the leader of the Persian search party along with a ‘large sum’.

Alexander I (498-452) hated the Persians but had not the strength to resist them. He did inform the states lying further south of the Persian military strength and apparently supplied Themistocles of Athens with vital timber for his fleet. During the second Persian invasion (480), he brokered the peace between Xerxes and the states of Boeotia under the hegemony of Thebes, sending Macedonian troops to Boeotian cities to safeguard them against attack. For these efforts he was, by special decree, declared ‘Philhellene’ (though his detractors took it ironically) and had his statue set up at Delphi. As a young man Alexander’s competitors at Olympia had tried to have him banned from the Games on the grounds that he wasn’t Greek. His Argive descent was accepted and he went on to come in equal with the first in the 200-metre sprint, a feat which was celebrated in an ode by Pindar. Like most of his descendants, Alexander was a patron of the arts.

Macedonia in the fifth century was economically mostly self-sufficient in grain, cattle, horses, river fish, timber, minerals and pitch, and supported a large population. Although Alexander had taken advantage of the upheavals caused by the Persian invasions to increase his territory in Upper Macedonia, acquiring a silver mine to boot, his country was not yet as well organized and powerful as the leading Greek states. They nourished covetous designs on Alexander’s kingdom and after the Persian defeat became more active and rapacious in the north.

It was therefore fortunate that Alexander’s son Perdiccas II (454-413), contemporary of Pericles, was highly skilled on the political tightrope. It was during his reign that Amphipolis, a trading town on the river Strymon, was founded by Athens whose subsequent aggression in the area was one of the main causes of the disastrous Peloponnesian War. Nimbly, Perdiccas, who changed alliances nine times, managed to keep his frontier state intact. Thucydides wrote at the time that the cantons in Upper Macedonia, due to mountainous terrain, were semi-autonomous under their own, albeit subject, leader while the rest of the country was under a single king.

Continuing upheavals due to the Peloponnesian War and the adverse influence of the now powerful colonies on the Chalcidic Peninsula were perhaps among the reasons why Archelaos (413-399) moved his capital from Aigai to Pella now inland but then situated on a lagoon which was navigable from the sea.

One of the most outstanding of these early kings, he created a strong standing army (all Macedonian males were eligible for military service except the serfs) and strengthened his renowned cavalry. Long before the Romans set foot in the Eastern Mediterranean, Archelaos laid out a network of straight roads with fortifications, organized regional towns into administrative centres, and streamlined the tax system.

His court was a centre for the arts. He employed Agathon, the leading Athenian tragic poet; Thassalus, the son of Hippocrates, who advanced medical knowledge in Macedonia and the outstanding painter of his day, Zeuxis, who embellished some of the new buildings at Pella. In his old age Euripides accepted an invitation and left Athens in disgust after its brutal treatment of Dorian Milos. In Pella he wrote Archelaos, honoring his host, and his last play The Bacchae which was performed there before it won him a posthumous first prize in Athens. He died and was buried in the Macedonian capital. Archelaos is also said to have initiated the games at sacred holy Macedonian sanctuary, Dion, lying under Mount Olympus.

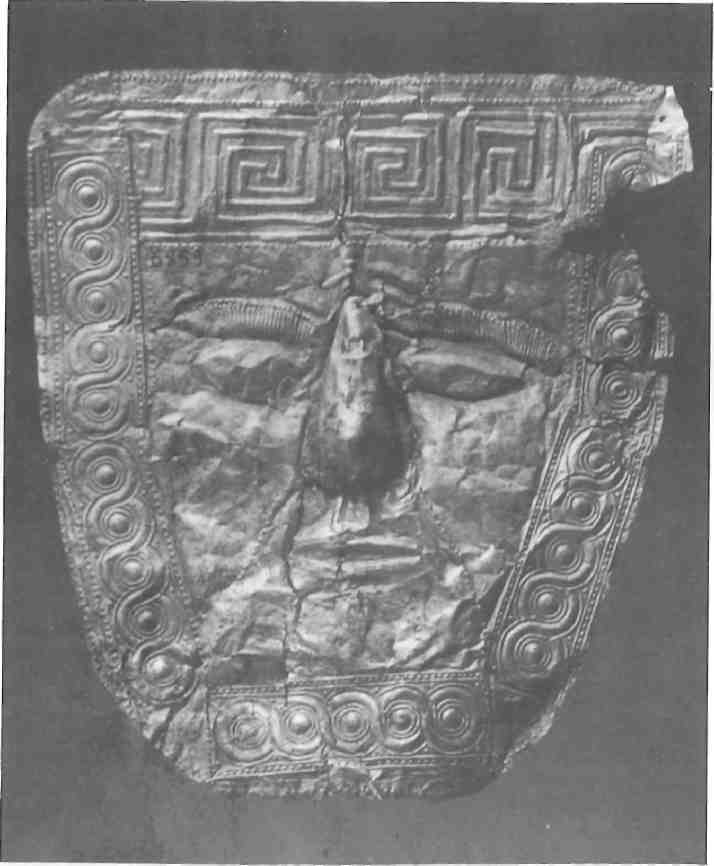

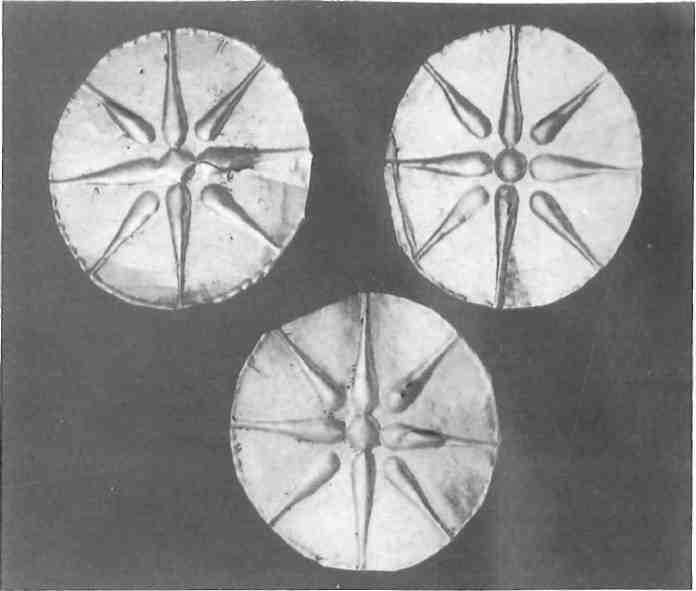

Small gold discs representing the eight-point Star of Vergina

Octodrachm of Alexander I depicting a mounted warrior wearing the characteristic

Silver stater minted by Archelaos, heir of Alexander I, with mounted warrior and, on the reverse, his name and a goat

Macedonian sunhat (Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris)

After the reign of this ‘sun king’, who died in his prime leaving no experienced heir, dark days fell on Macedonia. Orestes, Aeropos II, Pausanius, and Amyntas II followed in rapid succession and suffered violent deaths. Internal instability was compounded by interference from other Greek states and the constant barbarian threat to its northern frontiers received scant gratitude from southern Greece for keeping the Illyrians, Paeoneans and Thracians at bay.

During the tumultuous reign of Amyntas III (392-368) the Illyrians finally broke through the defences and Octodrachm of Alexander I depicting a mounted warrior wearing the characteristic Macedonian sunhat (Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris) overran much of the country. The desperate, king managed with Thessalian help to repulse the invaders but was obliged to pay “Danegeld” to them. Meanwhile the Chalcidic colonies had annexed part of coastal Macedonia and were supporting a rival claimant to the throne. It took allied Spartan arms to retrieve it.

Anarchy continued and violence ended the year-long reign of Alexander II (369-368). The murderer, Ptolemy, briefly usurped the throne (368-365) until Alexander’s brother Perdiccas III (365-360) managed to regain it. He had just settled his dynastic problems when the well-informed Illyrians again attacked Upper Macedonia. The young king enthusiastically marched north against them only to suffer overwhelming defeat. Four thousand Macedonians lay dead on the battlefield together with their inexperienced king who left an infant as heir.

The country appeared to be now up for grabs, as neighboring states, Greek and barbarian, scented weakness. In this black hour the Assembly of Macedons elected the 23-year-old prince Philip II (359-336) and brother of Perdiccas, as regent. He had spent two teenage years as hostage at Thebes, then a major power, and had had an early introduction to the latest methods in war and diplomacy. He proved brilliant at both.

Using dynastic marriage as a diplomatic art (he had seven wives), dividing and ruling, destroying and reconciling, he resecured his frontiers and placed his country on a sound footing. He then began the relentless expansion of an imperial Macedonia and almost succeeded in forcing a United States of Greece. And so he left a powerful legacy to his equally brilliant son Alexander III (336-323), called “The Great”, who was destined to change the course of history.

Scooping Up The Sunlight

The sixteen points (sometimes simplified to eight) of the Star of Vergina, symbol of the ancient Macedonian Kings, and now officially of Greece itself, are really rays, and it isn’t a star at all, but a sun. How this emblem of the ‘sun king’ became emblazoned on the gold larnax of Philip II is beautifully explained by Herodotus in the folk tale about how the royal dynasty was established in Macedonia:

How Perdiccas got for himself the despotism of Macedonia I will now show: Three brothers of the lineage of Temenos came as banished men from Argos to lllyria, Gauanes and Aeropus and Perdiccas; and from lllyria they crossed over into the highlands of Macedonia till they came to the town Lebaea (kettle-town). There they served for wages as laborers in the king’s household, one tending horses and another oxen, and Perdiccas, who was the youngest, the sheep and the goats.

Now the king’s wife cooked their food for them, for in early days the ruling houses among men, and not the common folk alone, were lacking in wealth; and whenever she baked bread, the loaf of the hired boy Perdiccas grew double in size. Seeing that this happened ever since, she told her husband; and it seemed to him when he heard it that this was a portent, signifying some great matter. So he sent for the three laborers and ordered them to depart out of the country. They said they had a right to their wages before they departed; whereupon the king, when they spoke of wages, was moved to foolishness, and said, “That is the wage you merit, and it is that I give you!” pointing to the sunlight that shone down the smoke-hole into the house. Gauanes and Aeropus, who were the elder, stood aghast when they heard that; but the boy said, “We accept what you give, O king,” and with that he took a knife that he had upon him and drew a line with it on the floor of the house round the sunlight; which done, he thrice scooped up the sunlight into the folds of his garment, and went his way with his companions… So the brothers escaped and settled in a place from which by degrees they conquered all Macedonia.