This should not surprise. Kidnapping in the past has been a popular terrorist technique employed by that movement. Slavic aggression seeking outlet to the Aegean is nothing new, but there have been two powerful examples of it in relatively recent times which seem to cast light not only on the present ‘Macedonian Issue’ but on the seemingly intractable ethnic strife that has risen once again in the Balkans. One is the Macedonian Struggle as it manifested itself at the end of the last century. The second is the Communist-inspired Greater Independent Macedonian Movement which came closest to achieving its aims during the Greek Civil War (1945-49).

Not surprisingly, perhaps, each of these movements intimately affected the fortunes of a widely known and well beloved institution in Greece. The first, in effect, was the catalyst that brought the American Farm School near Thessaloniki into existence. The second provided its most dramatic (and traumatic) moments 50 years later. Both episodes provided insight and vivid human interest to the murky panorama of social chaos. A former archivist of the school researched the backgrounds of both.

As the Ottoman Empire began its final disintegration a century ago, a condition of great social instability arose, especially in the economically unviable but strategically located region of Macedonia. This area comprised the Ottoman vilayets of Bitola (Monastir), Kossovo and Selanik (Salonica). Later these were divided up and taken over by Serbia (Vardar Macedonia), Bulgaria (Pirin Macedonia) and Greece (Aegean Macedonia) in the two Balkan Wars (1912-13).

Although Unguis ticians recognized a Slavο-Macedonian dialect most closely related to Bulgarian late in the 19th century, the term Macedonia only referred to a geographical area, not to a separate national identity since there had been no Slavic Macedonian state in the past.

Claims to the existence of a Macedonian ethnos, however, were now made by all states with pseudo-irredentist aspirations. In attempting to seize supremacy in Macedonia, these rival nations relied on organizations. Some were cultural but most were armed guerrilla groups using terrorist tactics. The best known of these latter was the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) founded in Salonica just 100 years ago. It began as a movement comprising petty merchants, artisans and professional men like teachers. Along with its slogan ‘Macedonia for the Macedonians’ it was, however, soon appropriated by the Bulgarian Liberation Front and taken over by brigands. One of its aims was to publicize provocative acts which would persuade the world that the Ottomans could no longer control the area, thus hastening liberation. This was the background to the notorious Stone-Tsilka kidnapping, the first event to involve the United States intimately in the Balkans.

On the third of September 1901, a group of Protestant missionaries were on their homeward journey to Salonica after having given a summer course for Bible readers who were members of the Protestant communities in the village of Bansko in Eastern Macedonia. Life for these missionaries was perilous. Their work took them through mountain passes and remote areas.

Their group included, on this fateful journey, the Reverend Gregory Tsilka, an Albanian by birth who was a graduate of the Union Theological Seminary in New York; his wife, Katerina Stefanovna, a Bulgarian, who had studied in America at Northfield Seminary and the Training School for Nurses of the Presbyterian Hospital (now Columbia Presbyterian) in New York; and Ellen M. Stone, an American missionary from Boston, Massachusetts.

Suddenly the group was surrounded by a motley band of guerrillas clad in Turkish military uniforms and Albanian peasant dress. They were, in fact, Bulgarian revolutionaries and members of IMRO. Brandishing their arms, the bandits separated Miss Stone and Mrs Tsilka from the rest of the group. Pushing them through scrub and over rocks they led the women up the mountainside and did not pause until they had carried them far from the point of capture.

The rest of the party, after being held overnight under guard, was released at dawn. A Turkish peasant who had the misfortune to stumble into their path was summarily shot. The two hostages, however, were to remain in captivity for over five months.

Thus began the incident which was to attract worldwide attention in the press and arouse American awareness to the problem of security for Americans living in European Turkey.

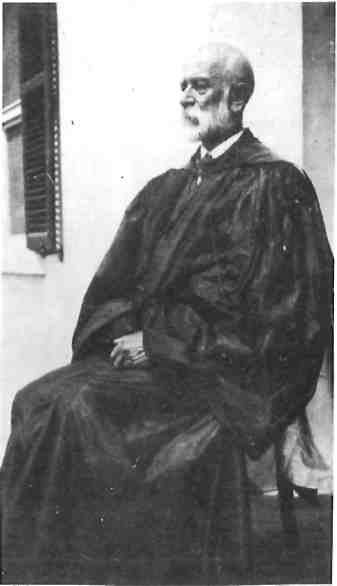

By 1894 conditions close to the Bulgarian-Macedonian border had become chaotic and dangerous due to the intensity of the Macedonian Struggle. Thus the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions decided to open in that year a mission station in Salonica. Three railroad lines had opened from the city which meant that missionaries could safely reach villages along the railroad lines. Dr John Henry House, who later founded the American Farm School, was chosen to administer to the evangelical community in a wide radius around Thessaloniki.

He was a man of his time but also a visionary. With a natural bent for the land, a deep religious faith, a turn-of-the-century missionary’s concern for ‘christianizing’ and saving souls, he had a dream: that of founding an educational institution for Balkan youths.

Ellen M. Stone had been a missionary for 23 years and had spent a large portion of her mission in European Turkey. The American-trained Katerina Stefanovna Tsilka who had begun her missionary work with her husband in Korytsa, Albania, was, at the time of her capture, six months pregnant. It was not the first time that the brigands had kidnapped victims to raise funds to supply their bands with guns, food and clothing. It was, however, the first time in the history of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) that any of its members had been kidnapped and may well have been the first time that any American citizen had been taken hostage by European bands.

Days were to pass after the capture of the women before the bandits contacted another missionary living in Semakov, Bulgaria, and handed him a ransom note demanding 125,000 US dollars. Despite the fact that the brigands’ messenger was told that it would be impossible to raise such a large sum, the revolutionaries remained adamant. There is no doubt that the ransom money was the principal motive for the act, but a secondary motive was also apparent: the Bulgarian revolutionaries wanted to show that the Turkish government was unable to protect foreign nationals living under its rule and they hoped, in this way, to arouse American antipathy for the Ottomans.

Indeed, from the beginning the incident focused American attention on the problem of security for its nationals in European Turkey, and the American government and the ABCFM were well aware that any measure they took might set a precedent: to give in too easily would encourage other kidnappings.

At first the ABCFM felt assured that the American government ‘would insist on the Turkish government’s duty to provide the required ransom, even though it may be obligated to advance the same in view of the poverty of the Turks.’ The Board informed the United States government that it would ‘provide the ransom were it to be provided in no other way.’

When it was ascertained that the bandits were of Bulgarian origin. President Theodore Roosevelt thundered that he would ‘hold Bulgaria responsible to the full measure of proof.’ The American government, however, refused to recognize or to deal with the brigands and the ABCFM then reconsidered paying the ransom because, in the words of Ellen Stone’s brother, such payment would ‘put premium upon brigandage and incite repetitions of this grave offense.’

Nonetheless, relatives and friends of the victims started a fund in America and England to raise the ransom and 65,000 US dollars was eventually collected. The sensational aspects of the kidnapping attracted the attention of the international press which kept a running tabulation of the growing subscriptions. The brigands, gleefully following the news, were loath to close negotiations while the amount of the ransom was still growing, and the ABCFM was forced to ask that all public statements be discontinued.

While all this furor was occurring on both sides of the Atlantic, Ellen Stone and Katerina Tsilka were living under the most extreme conditions in the primitive mountains of Macedonia. To keep out of sight, the band changed hiding places under cover of night. For five months the captors and captives spent the days hiding in dark, frozen caves, the only amenity an occasional fire built at the mouth of the cave which, in the absence of ventilation, proved nearly suffocating and erased the sweetness of the warmth. To add to their misery they feared that their captors might kill the pregnant Mrs Tsilka to rid themselves of her burdensome problems.

Yet they were not treated with indignity. When the bandits insist that the women listen to a daily reading of Karl Marx, the women were able to strike a bargain: if they had to suffer Karl Marx, then the bandits would have to suffer the word of God. So it was that as the group moved from one hideaway to another in the rugged mountains, the women listened to their captors reading Das Kapital – and the brigands listened to the missionaries reading the Bible.

On a cold winter night in January, after ten hours of travel on foot and horse through the frosty mountain passes, the group arrived at a deserted hut. It was here that Mrs Tsilka gave birth to a healthy girl whom she named ‘Ellena’.

lNo bed, no clothes, no convenience… not even water,’ she later wrote for a popular, Victorian magazine, McClure’s. Tire was all we had… but in spite of it the room was very cold. “No”, 1 said, “I shall never pull through. If I survive the pain the cold will kill me…'”

After the birth, Miss Stone impulsively handed the baby to the chief of the brigands when he arrived to see the newborn and it was an immediate breakthrough. The infant touched the chieftain’s heart and the mother realized that now, within the bandit’s code, it was a matter of honor that he protect the child. ‘He was no longer a brigand to me, but a brother, a father, a protector to my baby. He meant to spare my child.’ As a gesture of friendship the chieftain presented Mrs Tsilka with a chieftain’s costume. At the first cry from the baby there had been some talk among the bandits of murdering it lest its screaming expose their location. The bandits for the great part, however, were overjoyed: no other band could claim the distinction of having a baby born in its midst and they honored the event by carving the name ‘Ellena’ on their weapons.

‘Now Mrs Tsilka and I pray you from the depth of our hearts to do all that is possible to finish the work of our liberation. For 132 days we have been captives. Is this not enough?’ wrote Ellen Stone in a desperate plea to the missionaries. ‘In spite of all the suffering and privations mother and child progress in health but you must under-stand,’ she urged, ‘that they must be placed in winter quarters… before the winter cold increases.’ Although brave enough during the first weeks, they were reaching the limits of despair.

The responsibility for the negotiations with the revolutionaries had been given by the ABCFM to John Henry House, who had been a missionary in the Balkans since 1872. He spoke several Balkan languages, knew the local dialects, and had, throughout his mission, made friends with many people from prime ministers to peasants, and was trusted by most sectors of the Balkan polyglot communities. House served as a co-ordinator between the Turkish authorities, the missionaries in the field, and the American government, and it was he who impressed on the Vali, the Turkish Governor General in Macedonia, and the American Consul General in Constantinople, Dickenson, that if Turkish troops were sent out in pursuit of the bandits the women might be murdered by their captors.

Shortly before Christmas 1901, Dr House was brought a letter addressed to him by Miss Stone, with an explanatory cover letter written by an agent of Dickenson. Dr House met the bandits’ requirements that they would only come to terms with an agent who spoke Bulgarian and whom they could trust. Dickenson’s letter appointed him as principal intermediary for the dangerous task of contacting the brigands in the icy reaches of the Macedonian mountains and delivering to them, if they would accept it, the reduced ransom now fixed at 65,000 US dollars.

Dr House began his journey through the mountains from Serres to Bansko in the beginning of January 1902, on a trip that would take him three days. He travelled at first without guards to avoid attracting the attention of the Turkish authorities whom he feared might plunge in to capture the bandits regardless of their captives’ welfare, but on the third day he employed two guards to protect him in that stretch most infested by bandits. The missionary work he usually did in this area was a sufficient disguise to conceal his real purpose.

After a wait of eight days, contact was made. The three armed and uniformed revolutionaries with whom he met in the lonely and eerie mountains around Bansko, ‘not only seemed rather formidable,’ he wrote ‘but made it known to me that I was in their power. Their uniform was of a coffee colored brown homespun with white legging cloth strapped about their ankles and lower limbs, and a sort of moccasin worn by villagers on their feet. They were quite commanding in their appearance and seemingly well educated. They were armed with modern rifles and carried their knapsacks and heavy cloaks with them.’ The leader of the group presented him with letters signed by Ellen Stone and Mrs Tsilka and a letter from Dickenson’s agent agreeing to the brigands’ terms. Dr House reluctantly consented to deliver the money in gold coin to the kidnappers ten days before the release of the captives. Further attempts to meet with the bandits to complete the plans for the release were unsuccessful, however. The local Turkish military commander, learning that Dr House was acting as an agent, realized that the bandits must be near and had placed hundreds of soldiers on guard throughout the area.

To throw the Turks off the scent and to confuse the scores of reporters who were hampering the negotiations as much as the authorities, Dr House surreptitiously bought enough lead to match the exact weight of the ransom in gold. Stuffing this into bags, he ostentatiously loaded it onto a horse and carried it from the village to the railroad station where the bags were placed onto a train for Constantinople.

Observers, seeing that the ‘ransom’ was bound for Constantinople instead of the mountains, assumed that the negotiations had failed and that the money was being sent back to American authorities in the Ottoman capital. The ruse had worked and the press printed cartoons satirizing the bunglings of the missionary-negotiator.

With the press and the Turks occupied, the opportunity for a meeting arrived and four chiefs appeared at the place where Dr House was staying, divided the booty among themselves, shook hands with the missionary, and speedily departed.

Three weeks were to pass, however, before, on the morning of February 23rd, 1902, Mrs Tsilka and Miss Stone, with the infant Ellena, were released near the Macedonian village of Strumitza.

According to historian Douglas Dakin, the IMRO used the ransom to buy arms to instigate an insurrection near Monastir in August 1903. In reprisal, the Turks massacred hundreds of Macedonian peasants in what is known as the Ilinden Massacre. It is almost certain that the first boys brought to the Farm School in that year were orphaned by the Ilinden massacres.

On the night of January 29, one of the coldest and longest of the Macedonian winter, a force of Communist guerrillas lay hidden in the American Farm School cemetery. Towards 10 pm they crept under a moonless sky towards a thicket of trees that surrounded the pool across from Princeton dormitory. About 20 members of the band ran into the hall, awakened 37 boys and four young assistant instructors. At first the boys thought it was a prank, but as they came more fully awake and saw the armed men clearly they realized that it was not a joke. The boys were ordered by the insurgents to take one blanket and one loaf of bread from the kitchen before they were marched off into the freezing night.

The boys marched across the black marshes accompanied by some 18 to 20 Communists, a factor which would be likely to impede any chance of escape. The Communists, however, were exhausted. They had trekked three days steadily to reach the school. Without respite they were continuing their fatiguing march through cloying muck and were soon to turn into the mountains. Later, some of the escaping Farm School boys reported that many of the guerrillas dropped from exhaustion along the way.

The propaganda value of the exploit was considered by the Communists to be high. Their underground press heralded in bold type, “American Farm School boys join ELAS in the fight for freedom.” The kidnapping feat was also considered as a direct challenge to the Greek army which was responsible for the control of guerrilla movements in its area. To have a strike force of 20 insurgents kidnap a group of 41 boys a few kilometers outside the second largest city in Greece was to shake the confidence of the helpless population and to question the capability of the national forces, an indimidation lesson to the villagers. Each boy was instructed that should he escape from his captors and be recaptured he would be classified as a deserter from the rebel army and executed. To reinforce their point some of the boys were forced to observe the execution of an 18-year-old village youth who had fled and been recaptured.

The first two youngsters to escape did so the first night on the marshy flat. In the black of night one boy and a companion had sunk to the ground and remained motionless until the band had passed. One of the two lived near the spot where they were hidden. As the hostages and their captors disappeared into the dark the two youngsters ran toward the house where the father of one of the boys stood, rifle cocked, having heard the muffled steps. The one boy called to his father, who recognizing his son’s voice, lowered his weapon.

During the next week one by one and in small groups the boys continued to escape. By February 3, all but five of the abducted students were back at school. Now with only five captives to guard, the guerrillas were better able to prevent escape. Also the deeper the group advanced into the mountains, the harder it was for the boys to find

their way back through the bewildering and hostile topography. To add to their plight the boys noticed that the mountains were infested with other bands and the escapees had to avoid capture by them.

The last boy to escape returned to the school on April 6 after over two months as a captive. His father had been on the rebels’ side and some feared that he might join the rebels.

The graduation held in the spring of 1949 was the most emotional in the history of the school. The whole senior class which had been abducted was present to receive its diplomas – and not a few of them and many in the audience felt the boys were there through the grace of God. The graduates were ready to take their place on the soil, not unscathed by their experience, but with a heightened sense of the precious quality of human life.

The Communists lost the Greek Civil War later in the same year. KKE’s support for an autonomous Macedonia earned it a reputation for treason from which it never quite recovered. Although Communist regimes in neighboring countries have collapsed recently, the old ethnic tensions remain which is why the term ‘Macedonia’ continues to have such impact on the Greek national consciousness.

It was by no means the last time that the American Farm School became the victim of a ‘Greater Macedonia’. Thirty years after IMRO picked up the slogan ‘Macedonia for the Macedonians,’ it was revived, this time by the Greek Communist party (KKE). The newly-formed organization worked closely at first with its Bulgarian counterpart to abet Macedonian autonomy with the aim of sovietizing the whole area.

KKE’s 1925 declaration to ‘fight for the self-determination of the peoples of Macedonia, including their separation from Greece” of course provoked a strong reaction in Greece which had only liberated Salonica (now officially called by its ancient name Thessaloniki) and Aegean Macedonia a decade earlier. The Communist policy for an autonomous Macedonia turned out to be a serious tactical error which was revoked in 1935 – but not for long.

Towards the end of the Greek Civil War (1945-49) when the Communists made their final and strongest bid to take over Greece, the slogan was paraded once again. On January 29,1949, at the Communist Fifth Plenum, the discredited policy of support for an independent Macedonia State was revived. It was a desperate move which once again clamored for instant worldwide attention. In this regard what happened the same night achieved that aim.

Brenda Marder, former Archivist of the American Farm School and Book Editor of The Athenian is the author of the School history ‘Stewards of the Land’, distributed by Columbia University Press, New York, 1979.