Bold souls casting round for an inspirational Easter might consider a Paschal pilgrimage to hallowed Slavic shrines north of the border this year. Various fine and interesting churches from Macedonia’s Byzantine hey-day have notable frescoes, kept fresh, like those in Greece, under centuries of Turkish plaster. Some of the best depict movingly Christ’s passion, crucifixion and resurrection.

The monastery church of Panteleimon in the village of Nerezi, off a main road six kilometres southwest of Skopje, has compelling examples of the artistry and humanistic outlook of Byzantinized medieval Slavs. The spectacularly-sited little church high on a spur dates from 1164, built by Alexios Comnenos, grandson of Emperor Alexios I, who reigned on the Golden Horn from 1081 till 1118.

Architecturally, Aghios Pa-teleimon is regarded as provincial in character, its cloisonne brickwork dismissed as crude. The dome is sup-ported on four walls, corner bays are separated off and a large, well-lit space is left in the centre. The main cupola has an octagonal drum, four small cupolas each have foursided drums supported by arches and small columns.

It is the wall paintings which draw visitors to the church. They have a direct appeal and warmth of expression representing something unknown and new to the stern and reserved art of Byzantium at the time, says a Yugoslav tourist brochure from the old regime. Greek Byzantine art historian Manolis Hadzidakis considers the works of fun-damental significance, because “here, perhaps for the first time in the history of European art, emotion and pain are fully realized, not only on the faces and in expressive gestures, but also with the melodic lines of the composition dominated by great sweeping curves.”

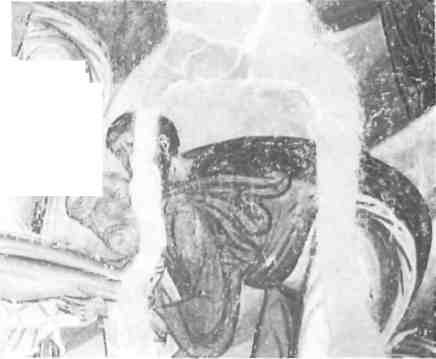

Hadzidakis cites in particular the Descent from the Cross and the Lamentation over the Body of Christ in which the elongated figures have an aristocratic elegance. Such mannerist elongation of figures, with clingy clothing, he notes, became almost a hall-mark of Byzantine frescoes.

The St Pan-teleimon style may also be studied in a dramatically sombre Resurrection in the church of St George at Kurbinovo on Lake Prespa, which gives the impression, says Hadzidakis, that the artist “was deliberately avoiding any reminiscence of the classical tradition.” The Kurbinovo frescoes are regarded as closely linked with those in Kastoria’s Aghioi Anargyroi built in 1018, with most of the wall paintings dating from a century or so later. The church is the oldest of the seven Byzantine churches still extant in Kastoria.

But before returning south, the Paschal pilgrim should head 45 kilometres northeast of Skopje to the church of St George at Staro Nagoricane, 10 kilometres from Kumanove, reported to be the barracks centre of the United Nations Nordic battalion stationed to keep the peace on the border with Kossovo. The 14th-century church has a well-preserved fresco of Pilate washing his hands.

The main destination of this trip, however, must be Ochrid, a small town now literally on a backwater, but throughout the days of the Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman empires an important centre on the Via Egnatia, the main road connecting Old Rome with New Rome, starting at Durazzo on the Adriatic and ending at Constan-tinople.

St Sophia, right on the lake, is rated one of the finest ecclesiastical edifices in the Balkans. Its 11th-century frescoes are the earliest in the region. Most show Biblical scenes, which may be compared to those in two of Thessaloniki’s leading historic churches, Aghia Sophia and the Panaghia Chalkeon (Our Lady of the Coppersmiths). The figures have expressive faces, “where linear contours are combined with stu-died plasticity,” says Hadzidakis.

The original domed basilica of St Sophia in Ochrid was built in about 1040 by Leo, the first archbishop from 1037 to 1056, who came from Constantinople. Many patriarchs are depicted, as well as St Basil the Great performing Mass.

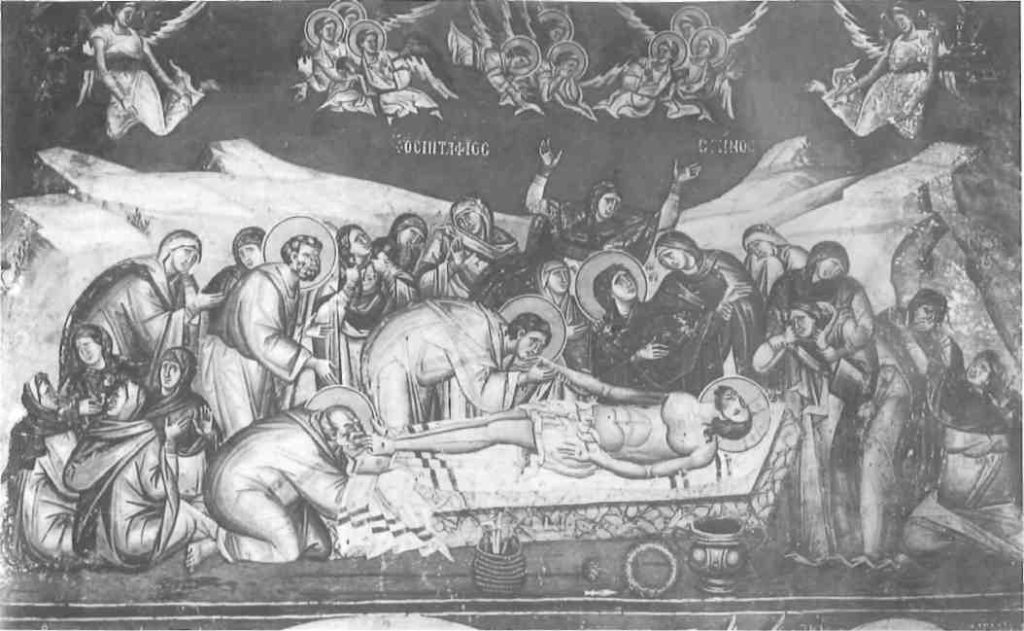

Also not to be missed at Ochrid is the church of St Kliment built in 1295, sometimes called the church of Mother Mary Perivleptos. A moving fresco of the Lamentation over the Body of Christ may be viewed, and a striking full-length portrait of the saint.

The artists are said to have been Slavs, Mihail and Euthije, who introduced everyday Slavic elements rather nos. His disciple, Naum, carried on the good work rather than keep within the imperial Byzantine style. Their works are seen as having a vigor and liveliness absent from the more static, ethereainess typical of Byzantine painting.

Kliment remains venerated by Macedonian Slavs for being the first in the region to use the Slavic language for religious services and general education. Born about 840, he studied under Methodius in his Bithynian monastery and went with him and his brother, Cyril, both from Thessaloniki, in the mission mounted, by invitation, in the 860s to evangelize the Slavs of Moravia, with the aid of the marvellous new alphabet Cyril devised to translate the Bible into Slavic.

Back in Ochrid after the master missionaries’ deaths, Kliment orga¬nized a brilliant, large-scale training scheme for Slav clergy to evangelize the local masses. Appointed bishop in 893, he founded a monastery and church by the lake, and died in 916 on July 27, the Orthodox feast of Aghios Panteleimonos. His disciple, Naum, carried on the good work.

The church of St Naum is on a hill at the southern-most point of the lake, a pleasant day excursion from the town by boat, or a 30-kilometre bus ride. The location is lovely, with a view over to Albania. The saint’s tomb is in a side chapel.

By the monastery is a fish restaurant recommended for its trout, eel and pastrmka, a local specialty served vegetable-stuffed and charcoal-grilled. Diners may gaze into the depths of Europe’s deepest lake set in mountains rising to more than 2000 metres on all sides, the area to the east forming Galicica National Park.

Ideal dining companions here would be a pair of professors of Byzantine history, Aikaterini Christofilopoulou of the University of Athens, and Eleni Glykatzi-Ahrweiler of the University of Paris. Their writings on the political history of the Slavs in Macedonia show why the Byzantine imperial fist lay so heavily in the area in the 11th and 12th centuries, when the main frescoed churches were created.

“Byzantinization became the key imperial policy for coping with the Slavs,” writes Professor Ahrweiler. Thorough Christianization and Hellenization was achieved largely in the period 810-860, after the setting-up of the themes (military provincial dis-tricts), Macedonia by about 802, Thessaloniki by about 836 and Strymon by 899. Slavs thus became subordinated to the Byzantine administrative structure.

The peaceful co-existence that de-veloped was ascribed to the Slavs’ con-version to Christianity, taken to mean their cultural assimilation. But though Macedonian Slavs would sing and pray in Greek, even in the tenth century, Slavic uprisings occurred, if usually incited by Bulgaro-Slavs.

The Sklavenoi had come from the forest steppes round the Dneiper, north of the Carpathians, explains Professor Christofilopoulou. They invaded Greece early in the sixth century, origi-nally as a subject people of the Avars. Their joint raids spread over most of Greece by the end of the century. Freeing themselves from Avar control, the Sklavenoi gave up nomadic life and took advantage of the opportunity offering to settle down on Byzantine territory.

The emperors at the time were en-gaged in the east, fighting off the Per-sians and Arabs newly converted to Islam, but by 591 began counter-attacking against the Slavs. By mid-seventh century they formulated systematic measures aimed at assimilation. Exchange of populations from one area to another was a favorite ploy; it might be called ‘ethnic cleansing’ today.

The wall paintings from the church of Saint Pandeleimon at Nerezi are, in the words of Byzantinist Manolis Hatzidakis, “a key to understand the pictorial art of the 12th century.” The Entombment is an example of this mannerist style

Some 30,000 Slavs were resettled in Bithynia in Asia Minor in 680. Rather than fight in the Byzantine army, 5000 or so defected to the Arabs, whereupon the Byzantines turned and routed them. Greco-Byzantines were then sent to populate former Slav lands. The policy continued on into the ninth century. Constantine V, emperor from 741 till 775, is said to have forced 200,000 Slavs to Asia Minor.

The emergence of Macedonia as a vital Byzantine centre, “the bulkwark and intellectual beacon of Byzantium’s Balkan parts,” (to quote Thessaloniki historian Anna Tsitouridou), was due above all to uthe peace which prevailed after the Byzantinization of the Slavs,” adds Professor Ahrweiler.

The Arab capture of Thessaloniki in 904 further motivated Constantinople “to create a stable military and political centre out of the area which the Slavs had ravaged.” The result was the new phase of prosperity in the 11th century, which continued till Robert Guiscard led the Normans into the Balkans via Durazzo in 1081, moving down to take Skopje and Kastoria and attack Thessa-loniki in 1185. That marked the end of Thessaloniki’s period of brilliance.

Two troubled, confused centuries followed, fraught with civil war, popu¬lar uprisings, religious and ecclesiastical strife. When Emperor Manuel Comnenos died in 1180, Constantinople had lost the Balkans. Serbia, led by Stefan Nemanya, became independent by the end of the century. When he withdrew to a monastery, his brother, Sava, emerged from another one in 1219 to establish the Serbian Orthodox church. The Serbs founded an Empire that stretches from the Danube to Thessaly but lost everything they had at the catastrophic Battle of Kosovo (1389), a story never more movingly told than by Rebecca West in Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. Ottoman domination of the peninsula set in for 500 years.

Anguish in the faces, figures and scenes of the frescoes in the Ochrid churches perhaps expresses the impact of the unsettled times on the slovenska dusa – the Slavic soul – living still under Byzantine garb, as Romiosyne survived under Turkish rule.

The Descent from the Cross in the monastic church of Saint Pandeleimon, Nerezi, dates from about 1162

Ivo Andric, the Nobel Prize-winning Bosnian novelist, said the Ottoman occupation of the Balkans opened a great hole in history for Serbia, Bos-nia and Macedonia. The only means by which Slavs could express their emotional reaction to the cruel realities of the Turkish domination was in traditional folksongs and stories.

Thirty years ago (though it sounds like yesterday), James Leech, an Englishman lecturing at Skopje University, talked of the problems facing Slav Macedonians in a BBC radio interview.

Visitors to the FYROM might note that visas are needed and can be bought at the border reportedly for about 25-27 Deutsche marks or for US dollars. Hotels are also likely to require payment in marks or dollars.

Thirty years ago (though it sounds like yesterday), James Leech, an Englishman lecturing at Skopje University, talked of the problems facing Slav Macedonians in a BBC radio interview.

The Yugoslav Embassy in Athens represents only the rump state and has only hearsay information on the new republics. A train leaves Athens at 9pm arriving at Skopje at 10.17am and trains leave Thessaloniki for Skopje at 7.20 and 9am, the latter arriving at 12.45.

“They’ve never been really free to face their past before. First of all the Byzantines wanted to make them part of the Byzantine Empire; then the Turks came and wanted to make them part of the Ottoman Empire; then Serbia and Bulgaria in the 19th century tried to make them part of their kingdoms; and before the last war, when they finally escaped Turkey, Serbia again wanted to make them part of Serbia.”

Bring on the trout. But by the waters of Lake Ochrid, before savoring its fish, it may seem a not unreasonable gesture to cede a little of essential Macedonia to Slavs, who. have shared its soil with Greeks, and others, for 1500 years. How else can a stranger guest from over the border join in wishing those around Kali Anastasi in sortie Orthodox church?