Interviews taken by our political correspondent with Romanian President Iliescu and other leaders stress the cordial relations which exist between Bucharest and Athens.

A people lacking in material goods but rich in hospitality, a country struggling to come out of one of the most repressive dictatorships in Europe, an electorate with the choice of tens of political parties which recently put on an American-style election campaign. This is current-day Romania and the Romanians, as seen by a foreign correspondent who visited Bucharest in the midst of its recent presidential elections.

A country where whole blocks of impressive neoclassical buildings stand empty and abandoned, a constant reminder of the legacy of economic ruin left by ambitious dictator Ceausescu and of the desperate need for foreign investment that will restore at least part of Romania’s former splendor. And yet, at the same time, a land of rivers, mountains and rich farmland, of snow-covered winter resorts in the Carpathian Mountains where the legend of Dracula lived and died, a land of sandy beach resorts on the Black Sea.

This is Romania that awaits to be reborn unto itself, and then rediscovered by the world.

PRESIDENT ILIESCU

Recently elected President Iliescu, who won 60 percent of the vote in the second round of elections last October, complains that the Western press has painted a simplistic and erroneous picture of him as a ‘neo-communist’ leading a camouflaged continuation of the tyrannical Ceausescu regime. He claims that this distorted picture, which has influenced Western governments, is the opposite of the truth.

Though a senior member of the Communist hierarchy, Mr Iliescu in fact actively opposed Ceausescu since 1971, favored the liberalization of the system, and was demoted by the Communist strongman as a result of this. His popularity, summoning him to action by public demand in 1989, lies in the fact that he represented an anti-Ceausescu, pro-democracy force.

Like that of all Eastern European countries, Romania’s key problem is economic, Mr Iliescu emphasizes, but unlike the leaders of many of them, he is ‘realistic’. He now realizes that the West did not have the resources to offer assistance on a massive or meaningful scale, and that the struggle for economic survival will be a long-term one.

However, he complains, the West was not frank in admitting this. Instead it found excuses in the perceived domestic situation in Romania, saying that more steps towards demo-cracy had to be taken, more structural changes made, and claiming that a semi-communist regime allegedly still prevailed. The Romanian president maintains that security and intelligence agencies, as in all democratic countries, are never employed for domestic surveillance or the suppression of citizens.

Mr Iliescu also gives the appearance of being very conciliatory towards other opposition parties, even with his main rival, Emil Constantinescu. Though also a former member of the Central Committee of the ruling Communist Party, he is now leader of the ‘right-wing’ Democratic Convention. The President’s party, the Democratic Front for National Salvation, a melange of ex-communists and reformist liberals, promises to pursue the formation of a government that represents as many political forces as possible.

Speaking on foreign policy prob-lems, Mr Iliescu concedes that the question of the Hungarian minority and the consequent problem with Hungary over Romania’s northern region of Transylvania, as well as the dispute with Russia over Romania’s demand for the ‘repatriation’ of Moldavia, are serious foreign policy headaches for Bucharest. But, he insists there is no risk of these problems degenerating into military confrontation, nor of Romania developing any domestic crisis even vaguely resembling the present situation in Yugoslavia.

On relations with Greece and the Moslem influence in the Balkans, President Iliescu said that “the common roots of Orthodox Christianity” were indeed a factor that linked and helped maintain good relations with Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece. He said that common Orthodox ties were not old-fashioned notions, but still valid today, influencing not only the average Romanian citizen but also its politicians. He added that Romania, however, was not so immediately concerned as Greece over the Moslem presence in the Balkans, since unlike Greece it had no significant Moslem minority. He added that Bucharest, however, was aware of the Moslem issue in the Balkans and was bearing it in mind.

VASILI IONEL

As a Minister to the President and responsible for defense and security, Mr Vasili Ionel is seen as a ‘power behind the throne’. He expresses Romania’s concern for the instability in the Balkans generally and the events in former Yugoslavia in particular. Unlike other countries, Romania, he says, has been particularly affected by the UN-imposed embargo on Serbia and the disruption of Bucharest’s trade and interdependent economic relations with the former Yugoslav republic. It is not just a question of the loss of import-export trade, he explains, as in other countries, but of bilateral ventures. There was, for example, a joint production of jet fighters with Yugoslavia using British Rolls Royce engines, as well as other industrial projects.

Mr Ionel says that Romania is fully applying the embargo, despite serious losses, and has invited a large number of foreign observers to see this for themselves. Romania, he complains, is not receiving any compensation from either the West or any international bodies as a result of the disruption of its projects with former Yugoslavia.

The Minister to the President says Romania now tends to agree with Greece that the break-up of Yugoslavia and the recognition of its component republics was too hasty. But, he says, the process is now irreversible.

Mr Ionel sees eye to eye with the President that Romania’s primary foreign policy concerns are Hungary’s intentions over Transylvania and Russia’s over Moldavia. He notes that Hungary is following the “usual tactic” of first asking for respect of the cultural identity and rights of the Magyar minority (it accounts for seven percent of the total population). This, he says, may well conceal political interests which eventually could develop into territorial claims over Transylvania.

As for the region of Bessarabia in the Ukraine, and the now independent former Soviet republic of Moldavia, bones of contention between Romania and Russia for decades, Mr Ionel says Bucharest’s position remains that they are Romanian territories which have been forcefully separated from it since World War II. Furthermore, he says, the Soviet Union infiltrated Russian peoples into Romanian-populated areas there in order to ‘dilute’ them. Then began a process of de-Romanification by dispersing Romanians to other parts of the USSR in order to weaken their cultural identity. He concedes, however, that the Romanian aim to reverse this process is a long-term and difficult one and should be handled carefully so as not to cause excess friction with the Ukraine and Russia.

Similarly, Mr Ionel says, Bucharest is not so naive as to expect that the Ukraine will easily agree to give up four areas in Bessarabia which Romania sees as its own. But he says talks have begun with the Ukraine in the hope of signing a political treaty.

In all cases, the presidential adviser rules out the possibility of the use of force by Romania to regain Moldavian and Bessarabian territories. As for Hungary, he adds, Bucharest and Budapest have an agreement on military cooperation. He says this includes exchanges of visits, observation of military manoeuvres, and an ‘open skies’ policy for overflights. Indeed, Ionel claims, this policy with Hungary is a “pioneering example” that could be imitated in Europe and the world at large.

TEODOR MELESCANU

With many years of service at the United Nations, Deputy Foreign Minister Teodor Melescanu, was the most outspoken of the Romanian government officials. Dismissing the view that Romania was following a ‘defensive’ approach to its problem with Hungary over Transylvania, and an ‘offensive’ one with Russia over Moldavia, Mr Melescanu said there was no comparison to be made between the two issues. In the one case, Hungary is raising issues based on the presence of a Magyar minority. In the other case, Moldavia and Bessarabia have always been part of Romanian territory that was forcefully annexed by Stalin.

As with the President and other officials, Mr Melescanu rules out the possibility of a military confrontation over either issues. But, because of concern that Hungary could use its minority to lay territorial claim (for example, Hungary wants to establish a Consulate in Transylvania), Romania is pursuing a treaty which would provide written guarantees of peaceful relations.

On Moldavia, he says, Bucharest’s intitial goal is cultural and economic integration. He says that prior to adopting a stronger stand, Bucharest must first convince the overwhelming majority of Moldavians that reunion is to their advantage. He also points to practical difficulties, such as the lack of telecommunications (to call Moldavia one still connects through Moscow) and of ‘adaptable’ railway lines (the width of the railway tracks differs between Romania and the former Soviet republics).

As for the United Nations-imposed embargo on Serbia, Mr Melescanu, like his compatriots, says it hurts Romania more than any other country, not only economically but also sentimentally. He, too, pointed out that, apart from trade across the Danube, the two sides had major joint production ventures, including fighter planes, washing machines, and a chemical factory in Serbia, and that they also have exchanged raw materials.

He said the embargo is being adhered to despite this, with the exception of “small-scale cheating” across the border such as the trafficking of cigarettes and petrol by private cars. In the latter case a private car will cross the border several times a day to sell its fuel on the other side. He said the Serbs understand the international pressure put on Romania and they have only asked for Bucharest’s support at the UN to obtain certain exceptions, such as heating oil.

Mr Melescanu agrees that “common ties of Orthodoxy” amongst Romania, Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece foster ideas of creating a “defensive wall” across southeastern Europe against Moslem countries.

As in Greece, says Melescanu, the Orthodox Church in Romania has played a key role in consolidating Romanian national identity and the country’s independence. The Church is concerned over Moslem influence from the East, and over evangelical preachings of the Vatican from the West. (The schismatic Uniate Church is of particular concern to the Orthodox Churches.) The Church in Romania currently favors dialogue with the Vatican so that a solution on the Uniate issue can be found.

The common ties of Orthodoxy have strengthened Greek-Romanian relations, says Mr Melescanu. The Greek presence in Romania goes far back into Byzantine times to a large Greek intellectual and commercial community leading up to the Greek-led anti-Ottoman revolution of the early 19th century. This has extended up to the present re-appearance of Greek business investors in post-communist Romania. To a degree the two countries, he says, see themselves as on the front-line between the Christian and Islamic world.

Of course, Mr Melescanu points out, the Turkish presence is minimal compared to Greece and, in particular, to Bulgaria. Furthermore, the small Turkish-Tartar Moslem community is ideologically attached to the orthodox Sunni division of Islam and not to the radical Shiites.

But Mr Melescanu says, Turkey has improved its image and influence in Romania since the Ceausescu over-throw through economic means – mainly with investments in basic consumer goods. Ankara has taken advantage of the incentives for foreign investments and established a number of small businesses. It has also offered help in difficult times, particularly during the harsh winter months.

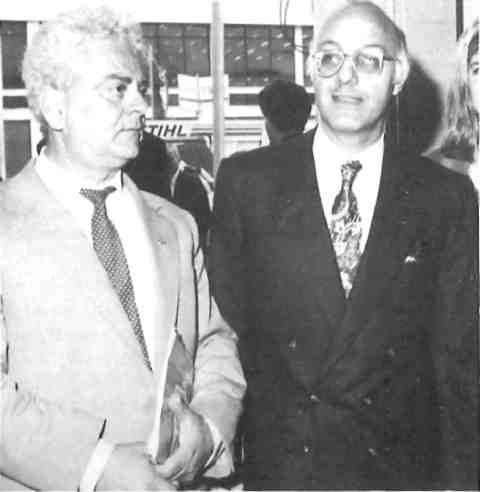

CHRISTOS ALEXANDRIS

Interesting points were raised by Christos Alexandris, Greece’s recently appointed Ambassador to Romania and a veteran diplomat who has specialized in Balkan affairs. Greece, he says, is often criticized by its western partners as being just “another Balkan country” which creates non-existent or unimportant disputes, such as over the name of Macedonia. Similar criticism, he says, is levelled at the Greek and Romanian Orthodox Churches’ concern over the Moslem factor in the Balkans and the encroachments by the Vatican.

But, Ambassador Alexandris points out, this attitude taken by the West is short-sighted. It should realize that strengthening the national, autocephalous Orthodox Churches in Central and Eastern Europe is one way of containing Russia’s attempts at influence in the region. He says there is a struggle for power among the various Orthodox Churches, and that the Russian Church is seeking to dominate the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate in Constantinople. Through such domination, the Ambassador says, it will be easier to realize the Russian goal of pan-Slavism in Eastern Europe and the Balkans.

In conclusion, it appears that democracy in Romania is vibrant – even rampant. Although many of the same people are in the higher echelons of power and in the civil service today as they were under communism, including the security apparatus, they show no loyalty to communism nor any desire to restore it in any form. Indeed, they all appear anxious to prove that, in reality, they have a record of opposing communism.

The press gives every indication of enjoying unlimited freedom, and no ‘man in the street’ appears to be afraid to speak his mind. On the other hand, there is widespread disappointment that embracing democracy has not quickly borne fruit with western lifestyles and economic standards.

Romania’s problem is almost exclusively economic and extremely serious. Government officials addressed make it obvious that the country is desperate for foreign investment. It is felt to be about the only way out of the present impasse. For this reason, Romania’s laws on foreign investment are among the most liberal and encouraging of any country in Europe. The provisions are more accommodating than even those of some Third World countries which, boxed in pseudo-Marxist-Leninist rhetoric until recently, would not have contemplated offering such daring investment benefits for fear of being accused of “selling out to the Western imperialists.”