The story of a Byzantine princess who ruled over the Holy Roman Empire for several years at the end of the 10th century, reads like a medieval winter’s tale peopled with kings and emperors, princes and courtiers, prelates and scholars, and set against a backdrop of royal trappings and solemn ceremonies, wars and treaties, plots and intrigues, loves and hates. All of these form an impressive mosaic centering on a lively young woman whose story begins when she was 12 and ends with her death at the age of 32 in 991.

The millenarian anniversary of her death has been celebrated throughout Germany this year and ends this month in Thessaloniki, once the second city of the Byzantine Empire, and a venue today substituting for her native Constantinople.

The political situation into which young Theophano was swept during the second half of the 10th century had developed into a major confrontation between East and West. During the reign of her uncle, the Byzantine emperor John I Tzimisces, the German king Otto I conquered the Kingdom of Italy and had himself crowned in Rome by the Pope, thus reviving the empire created by Charlemagne a century and a half earlier.

These events alarmed John Tsimisces whose policy had been to safeguard his provinces in Italy and Sicily and to prevent the spread of German power into the peninsula. Ever since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire 500 years earlier, the Byzantine rulers had claimed to be the only lawful and oecumenical emperors. Now a western sovereign, a barbarian no less, was claiming the glorious inheritance of Rome with the blessings of the Pope.

In order, then, to rectify this situation, John I Tzimisces proposed, as a diplomatic solution not so rare in those days, to unite the dynasties by marriage. In the past, however, all efforts to create an imperial union through marriages had failed. A major impediment is that no porphyrogenitus (born to the purple) princess could lawfully marry a ‘barbarian’, that is a man not of the Byzantine nobility. This was understandable as the bride carried land and even imperial rights to the Byzantine throne with her dowry. Even so, exceptions might be made, as, some years later, John’s successor, Basil the Bulgar-Slayer, was obliged by political expediency to give his sister Anna, a porphyrogenitus herself, to Vladimir the Great of Russia. But there, at least, there was the tie of Orthodoxy with the first Christian ruler of Russia.

In the imperial Byzantine scheme of things the concept of porphyrogenesis is so central that its origins are worth a short digression. This red color so dear to the emperors was extracted from a sea shell found in the Mediterranean. It was called “porphyry”, and from it, its color took the name. The imperial family held a monopoly on its use, employing it in their clothes, in the ink which the emperor used in signing public papers, and in the dye of his sandals. Not only that, but in the Imperial compound there was a wing called the Porphyro Palati, the Red Palace, in which there was a room hung in this same red where the empress gave birth to her children. Hence the phrase “born to the purple”. It was only much later when the empire was in dire financial distress that small pieces of cloth in this colored red were for the first time sold in the open market.

The successes of Otto the Great disturbed relations between East and West and to smooth them over, Otto sent several missions to Byzantium proposing that the porphyrogenitus princess, Anna, daughter of the Emperor Romanos II marry to his son, Prince Otto. The Byzantines at first were outraged at the audacious proposal of this uncouth westerner.

But when John Tzimisces ascended the throne, having murdered Nikiphoros Fokas with the assistance of his mistress Theophano, widow of Romanos II, he in turn proposed to the German emperor that his little niece, also Theophano, marry young Otto. She was 12 years old at the time and even though she was not born porphyrogenitus, she had quite adequate titles enough as a descendant of the noble Byzantine families of Skliros and Fokas.

It was a realistic political move on the part of John. Though a fine general himself who had won victories against the Bulgarians and Russians, his predecessor had been heavily defeated in southern Italy and John knew the main threat to his realm now came from the West. The proposed marriage, then, would quash any de facto German rights on the Byzantine Empire. Although a balance of power through marriage could only hold on a superficial level, it allowed the Byzantine emperors the possibility of continued influence not only on papal elections in Rome, but of keeping up alliances with the small independent Italian states and the kings of France.

The negotiations were subtle and hard, but the embassy led by Cardinal Gero, archbishop of Cologne, a man of great personality and influence, brought a happy solution to the whole affair, and he himself escorted young Theophano from her native city to Rome for the nuptials.

On April 14, 972, one Sunday after Easter, in the presence of Otto the Great and Empress Adelaide, in a great gathering of German, Italian and Byzantine nobility and courtiers, Pope John XIII performed the marriage rites and blessed the very young couple.

For nearly two decades, until her death in 991, Theophano was destined to write an important chapter in European history not only as a symbol of Byzantine cultural supremacy but as an example to female sovereigns of the period.

The domestic life of the young couple appears to have been a happy one, and Theophano worked closely with her husband, the crown prince, always accompanying him on his travels. Between the ages 17 to 20 she gave birth to three daughters and a son who afterwards became Otto III. The latter was born on the road from Aachen to Nijmegen for at this time sovereigns were constantly on the move, travelling with their courtiers and servants from place to place. It is said that Theophano never stayed more than 15 days in a row in one place.

She gave the name Adelaide to her first-born, after her mother-in-law, with whom she was not on the best terms, and Sophia to her second daughter in honor of her Greek grandmother. Neither girl married and both became nuns. The third daughter, Matilda, later married the King of Poland.

On her arrival in Aachen, Theophano knew no German nor Latin, but she learned quickly, because she was an intelligent, persevering girl. During her ten years of married life, peace reigned between the two empires whose unity she personally embodied. Otto was able to strenghthen the legitimacy of his dynasty, and John Tsimisces won a period of peace in Southern Italy.

On the death of Otto the Great, Theophano’s husband was crowned Otto II by Pope John XIII and she received the title of co-imperatrix.

But it was mainly after his brief reign when she became regent for their son, Otto III, then aged three, that Theophano made her main contribution to her age. She brought to the German imperial court the culture and customs of Constantinople. Western sources, rarely complimentary of Byzantium refer to her as “a blessing in education and a light of civilization”. She had asked many scholars from the East to come to her new country, and in this enlightened spirit she became a patron for the arts and letters. Illuminated manuscripts and examples of Byzantine jewellery were among the artifacts to travel West from Constanti-nople for the first time in the Middle Ages. The child-emperor’s most dedi-cated tutor was John Philagathos, a profound Byzantine scholar who later became archbishop and pope.

During her brief regency, Theophano influenced Germany not only culturally but in everyday life. It is said that her court, following Byzantine practice, introduced the use of forks at the dining table.

Theophano combined culture and hard-headed determination. On the death of her husband, his brother Heinrich, Duke of Bavaria, kidnapped the infant Otto III and enthroned him in Aachen as King of Germany in hope of taking over the regency himself and eventually the throne. Not only did Theophano get little Otto back but she supervised his education herself while at the same time performing her duties as empress. Following principles by which she herself was brought up, she instilled in her son a sense and desire for unity quite alien to the fragmentary political realities of the West.

Otto was crowned emperor in Rome five years after his mother’s death. In a palace he built on the Aventine he conceived the possibility once again of establishing a universal empire. Few can doubt that this sense of of the oecumene derived from his t lineage, the imperial meeting of Eastand West, and above all from the influence of his mother. Yet his contemporaries without his vision found him mystic and erratic. r Like his father, he, too, wished to marry a Byzantine princess, and it was only by a cruel turn of fate that he died while his future wife was on her way t from Constantinople to Germany.

Theophano’s regency had been remarkable. She stabilized the eastern borders of her empire; made a settlelment with the King of France; proved : to be a capable diplomat and chose the right people as her councillors. At the same time, the persons who worked for ι her had deep respect for her.

In what many have called the darkest century of Western Europe’s Dark I Age, Theophano brought to the German court from the most glorious city of its time the refinements of civilization in dress, decoration, manners and thought.

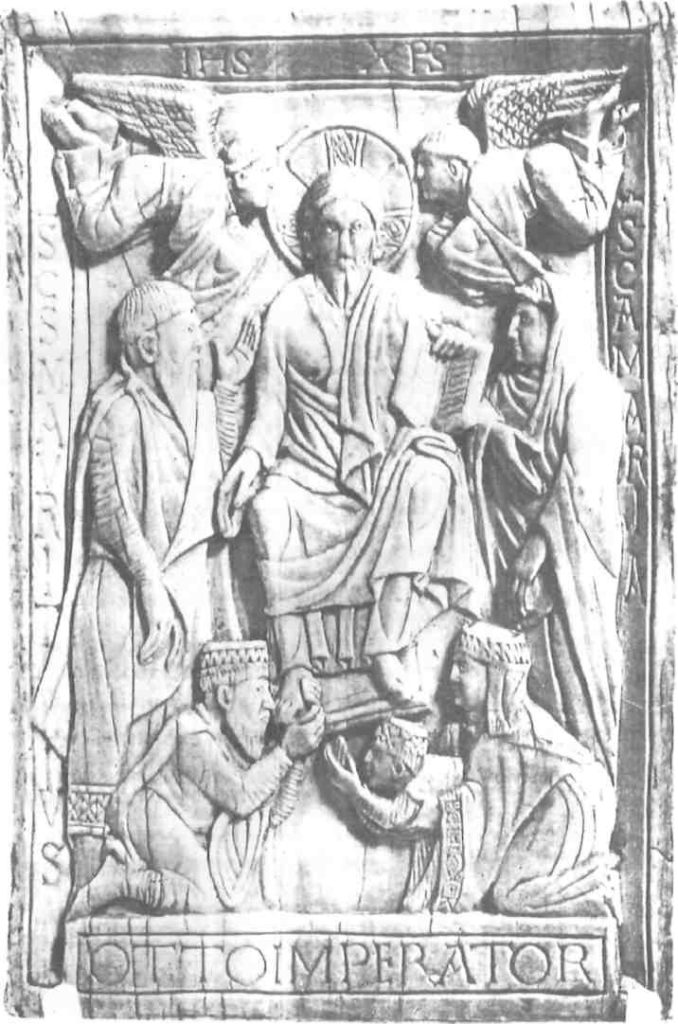

In the beloved city of her adopted country, Cologne, where architecture still echoes the splendid influence she brought with her from Byzantium, she was interred in the monastery of St. Pandeleimon as she wished, and there she still lies beneath the bas-relief representing herself, her husband and her son with the words engraved on marble: Domina Theophanu Imperatrix.

In celebrating the millennium of her death, a series of exhibitions began in Cologne last spring and will continue in Thessaloniki, (they are sister-cities) this month. Entitled “The Macedonian Renaissance from Byzantium to Germany”, it is attracting roundtable discussions, lectures, book displays and concerts. Above all, researchers and specialists are sharing new knowledge on this engaging personality.

Under the auspices of the Greek Consulate at Cologne, University of Thessaloniki Professor Konstantinos Kalokyris is presenting a study, in German and Greek, called “Theophano”. Participating, too, is the consul himself, Mr Panayiotis Karakassis, as weil as the International Center of Greek and German Scientific and Cultural Research under the initiative of Professor Evangelos Konstantinou of the University of Wittenburg, and many others – all with the blessings of the Orthodox Archbishop of Germany Augustinos. In Cologne, a symposium under the title “Byzantium and the West in the 10th century” drew experts from

Greece, England, Austria, Bulgaria and Italy together with a splendid exhibition of rare books and illustrations of 10th and 11th centuries gathered from all over the world, and 50 religious objects of the period gathered together under one roof for the first time. These included gospels, prayer books, meticulously worked artifacts in gold, silver and ivory as well as many priceless illuminated manuscripts. There was, as well, an exhibition de-voted to Byzantine Thessaloniki. Two Orthodox vesper services were held in the church of Saint Panteleimon, accompanied by the 42-member chorus directed by Lykourgos Angelopoulos. Two concerts were also presented. The celebrations ended with a lecture on Byzantine music by composer and professor Dimitris Terzakis of the University of Berne.

Finally, a trip was organized by riverboat up the Rhine, which traced the same journey that, 1000 years ago, conveyed the body of this extraordinary woman from Nijmegen to Cologne, in order that she be buried at the

Benedictine monastery of Saint Panteleimon.

In Athens, at the Goethe Institute last October, Professor Gunther Wolf, a historian and researcher who has specialized on Theophano dwelt on her remarkable personality. Art historian Ekaterini Stefanaki also led a very interesting seminar on Theophano’s influence on the West in all aspects of art; enamel, gold, silver, ivory, illustrations of codices and woven silks.

On December 2 at the church of Saint George, the Rotonda, in Thessaloniki, an exhibition opens under the title “Theophano and her era”. From December 3 to 5 a symposium will be held under the auspices of the Goethe Institute, where a large number of specialists from various countries will gather. The program includes projections, a guide to the Byzantine and post-Byzantine monuments of the city and an excursion to Mount Athos.

As Europe strives again for unity between East and West, one woman’s remarkable attempt to achieve it is remembered and honored.