Melina Mercouri’s campaign for the return of the Parthenon Marbles to Greece calls into question the whole issue of the looted treasures of ancient civilizations, and whether they should be restored to their countries of origin. Are the marbles a special case, the symbol almost of Greece’s nationhood? Or should all of Greece’s plundered heritage be restored? If the principle of return were pursued to its logical conclusion, many of the great museums of the world would be stripped.

The sections of frieze and the metopes which Lord Elgin’s agents sawed and hammered off the Parthenon represent only a tiny proportion of what Greece has lost over the centuries. Rome started the process and pursued it vigorously. When Roman general Mummius laid waste Corinth in 146 BC as a warning to other Greek city-states to fall into line, that enormously rich city was plundered and vast quantities of statuary taken off to Rome. The Emperor Nero removed 500 statues from Delphi among many other depredations including the plunder of Olympia. Later, when Rome was under threat from barbarian hordes, the Greek art treasures went to Constantinople where many were destroyed in the recurrent fires that city suffered. Some survivors found their way to Venice and thence to Paris to stock the emperor’s vast Musee Napoleon.

After the Renaissance came the era of the ‘collector’, the ‘scholar’, the ‘connoisseur’. A Citizen Kane mentality of acquisition for its own sake emerged. From the 17th century onwards, collectors were the main threat – English and French gentlemen antiquarians with little to do and the time, money and resources to grab what they fancied.

If not the worst, Lord Elgin was most notorious. As British ambassador to Constantinople, he used his influence to get the permits he needed, which he then proceeded to interpret beyond all reason, subsequently getting the Sultan to rubber-stamp his excesses ex post facto. His later justification to a Parliamentary Committee that he was saving the marbles from being used for mortar by the Turks we can dismiss: we are not talking of stray columns and broken statues, but huge slabs of carved marble sawn off the Parthenon with specially imported saws made for this purpose. Perhaps Elgin’s abortive plan to borrow a warship to bring the entire Erechtheion back to Britain tells us all we need to know about his motives. As he said in a letter: “Bonaparte has not got such a thing from all his thefts in Italy.”

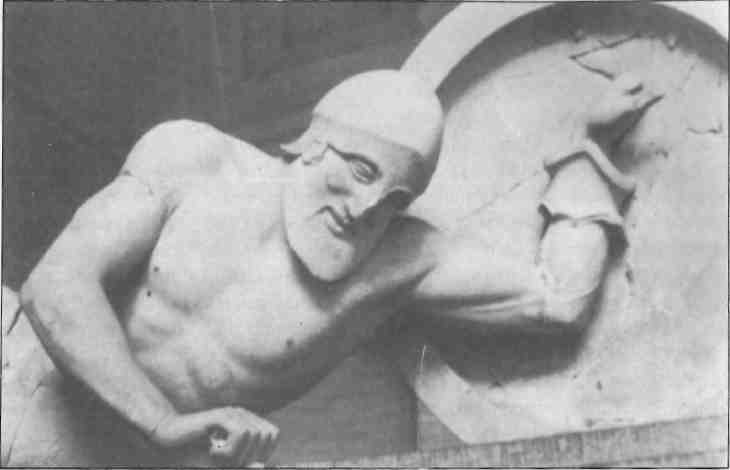

But Elgin was not alone. Another of Greece’s oldest Doric shrines, the Temple of Aphaia on Aegina, dating from about 490 BC, was similarly looted. A party of English and German travelers, including C.R. Cockerell, later one of the best-known architects of his day and designer of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, visited Aegina in 1811. They hired laborers and began to dig, quickly uncovering the main outlines of the temple. On the second day they were startled to find a piece of Parian marble, since the temple was of stone. It was the head of a helmeted warrior in a perfect state of preservation. Two pediments with 17 statues depicting scenes from the siege of Troy, as well as many fragments were taken off to Athens while local officials were formally claiming the finds. A bribe of 800 piastres quickly defused the situation.

The four men who jointly ‘owned’ the marbles had to decide what to do with them. The marbles were shipped to Malta and it was resolved to hold an auction on the island of Zante (Zakynthos), then a British protectorate. The reserve price was 6000 pounds. The Prince Regent sent the Keeper of Antiquities at the British Museum to bid up to 8000 pounds and – prematurely – a warship to Malta to pick up the marbles. The French would not go above 6000 pounds. Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria wanted to create for his future kingdom a collection of antiquities rivaling those of London and Paris, so he too sent an agent to bid. At the time of the auction the British agent was on Malta, believing it was to be held there. Ludwig’s agent put in the highest bid but refused to buy a ‘pig in a poke’ and would not ratify the purchase until he had been shown the plaster casts of the marbles in Athens. They are now in the Museum of Sculptures in Munich.

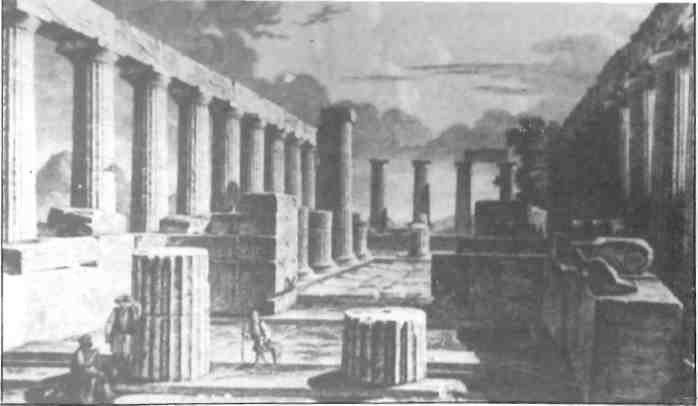

The same team held another auction on Zante in May 1814. On sale this time were 23 marble slabs from the cella frieze of the Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassae. High on a lonely hill in Arcadia, the temple was one of the most complete in Greece. The architect was Ictinus, designer of the Parthenon, and the temple had been raised in the fifth century BC to thank Apollo Epikourios – the ‘Helper’ – for delivering the community from plague. Cockerell copied the capitals at Bassae in his design of the Ashmolean Museum.

Cockerell and his friends arrived at Bassae after abortive digs at Eleusis and Olympia. The local Greeks, fearful of the attitude of the Turkish authorities, had tried to make the visitors leave, but they pretended to have a firman (Ottoman authorization) for what they were doing. Disturbed by the commotion, a fox bolted from under a mass of stone. Cockerell, hanging upside down over the stone, was startled to see a sculptured bas-relief depicting the battle between the Lapiths and the Centaurs. Still inverted, he made a hasty sketch, but told no one what he had found. Since the Greeks refused to dig and the owner of the land turned up with an armed bodyguard, Cockerell and company were forced to follow the path to ‘legality’.

They visited Veli Pasha, ruler of the Morea and son of the notorious Ali Pasha of Ioannina, at Tripolis. Vali issued a firman provided he was guaranteed half the spoils. The official dig began in July 1812. Not realizing the value of the finds and in the process of being ousted from his pashalik by the Sultan, he sold out his share for 400 pounds, and threw in documents of dubious validity needed for the removal of the marbles from the country.

The embarkation at Bouzi was dramatic according to Cockerell: the new Pasha’s troops arrived to intervene just as everything -had been loaded except one of the earliest known examples of the style of column known as Corinthian. The ship put to sea and the angry Turks hacked the column to pieces; but since Cockerell was not present at embarkation and since the column never left the site – fragments of it were found there in 1902-1908 – Cockerell must have had some curious reason of his own for inventing the episode.

At the auction of the Bassae marbles, the British had greater success. The Bavarians did not bid, since the goods on sale were artistically inferior to the Aegina marbles. The French bid 8000 pounds and the British 15,000 pounds. Presumably a system of sealed bids operated, for the marbles are now in the British Museum.

The spectacle of governments fighting a war using banknotes instead of bullets in pursuit of national prestige, and becoming receivers of stolen goods in the process, cannot have been an edifying one. The auctions had the effect of alerting the British to the value of Elgin’s loot, which Ludwig of Bavaria was known to be willing to pay for handsomely. After much horse-trading, Elgin was offered 35,000 pounds and took it. Just as Napoleon’s ill-gotten gains were being dispersed from the Louvre following the French defeat at Waterloo, the British Museum was becoming one of the great museums of the world, and the impact of the Elgin Marbles on European artistic taste was enormous.

The sorry tales of the Aegina and Bassae marbles closely parallel the saga of the Elgin Marbles. One fact that tells in favor of Cockerell’s group is that they removed fallen and buried statuary rather than hacking marble off standing temples as Elgin’s people did. The Parthenon was left, as an Athenian schoolmaster recorded in 1803, “like a noble and wealthy lady who has lost all her diamonds and jewellery”. As against that, Elgin at least got & firman first, even though he went beyond its terms. Cockerell’s men operated by trickery, bribery and outright theft.

Two other incidents complete the catalogue of the most famous 19th century depredations. On the site of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace is the Nike Fountain. It once included a magnificently sculpted centerpiece, now called the Winged Victory of Samothrace. The French consul found it and made off with, it in 1863. It is now in the Louvre.

Earlier in the century the French had resolved to restock the Louvre, now stripped of its Napoleonic loot. The consul-general in Smyrna was instructed that local consuls should purchase any available antiquities. In 1820, Yiorgos, a farmer on the island of Milos, dug out a tree stump in the path of his plough and found two halves of a nude female sculpture, two engraved slabs and a marble hand holding an apple. There were two French ships moored in the harbor, and Yiorgos told the French consul of his find, no doubt hoping for a quick sale.

Uncertain of the statue’s value, the consul sought instructions from Smyrna. In the meantime, Yiorgos sold the statue to an Armenian priest. There are several conflicting accounts of what happened next. According to one, when the Armenian tried to sent the statue to an official in Constantinople whose favor he was trying to regain, the captain and crew of one of the French ships seized the box it was in by force, fighting off the Armenian priest and his Greek supporters and spilling blood. The consul was in the thick of the fighting, wielding sword and staff. According to another version, the French bought the statue from the priest for 30 pounds. The Venus de Milo is now in the Louvre.

It was not until 1874 that the Greek government developed the muscle to take a strong stand. The Olympia Convention was an agreement between the German and Greek governments over the fruits of excavations. The main stipulation was that all Greek finds should remain in Greece. Signed at a time when the Germans were plundering Asia Minor with their usual single-minded thoroughness, the convention probably saved Greece from depredations which would have made what had gone before look trivial: it undoubtedly prevented the treasures of Olympia and Mycenae going to a German museum. But the gold of Troy did go to Berlin and disappeared when the city fell to the Red Army in 1945.

The wrongdoing of Elgin and others of his ilk is not in itself sufficient reason for the return of all Greece’s major art treasures. The case of the Venus de Milo, for example, is one where there are valid arguments on both sides. This was not a case of a great, visible monument being illegally, or at the very least immorally, dismembered, but of a statue previously unknown being dug up and sold, on the face of it legally, according to one version. The case for retention is at least arguable.

Since the marbles represent the cause celebre in this field, it is worth briefly rehearsing the arguments surrounding their removal. Insofar as opponents to restoration can produce coherent reasons for their position, they amount to these: firstly, that Elgin acted within the laws of his day; secondly, that had he not taken them, they would by now have been destroyed by the Turks, war or acid pollution; thirdly, that the British Museum, have bought them in good faith, has looked after them well and exhibits them to the public free of charge; fourthly, that Greek viewing charges for museum and sites are excessive and discriminatory; and fifthly, that a precedent would be set that could denude the museums of the world.

As far as legality goes, the Turkish firman, in the surviving Italian translation, allows Elgin to take “any piece of stone with inscriptions or figures”. That clearly refers to pieces that have already parted company with parent buildings: it cannot possibly be taken to have granted permission to saw and chisel great chunks off standing temples. As to the preservation argument, it is hard to support at all, considering some of the marbles were shattered during removal, some broken in transit, some lost at sea, some stolen and the survivors left outside for years at the mercy of the English weather.

It is said the British Museum looked after them well. Sir Jacob Epstein, the great sculptor and enemy of philistinism, did not agree. In 1939, it became known that for two years the head cleaner of the museum, with six unskilled assistants, without any professional supervision, had been cleaning the marbles with a solution of ammonia. Prior to this, they had simply been blown with bellows, the dirtier bits being scraped with a blunt copper tool. Before the ammonia cleaning began, some had been, according to the head cleaner, as dirty as a used fire-gate. Sir Jacob, who for years had been criticizing the restoration and cleaning methods at the British Museum, accused the authorities of ignorance, sloth and snobbishness.

The other arguments may be dealt with briefly. It is true the marbles are exhibited free of charge, for what consolation that may be to an Athenian laborer or pensioner who wants to see them. It is true that the Greek government’s charges are exorbitant and discriminatory against foreigners. The British government should certainly stipulate as a condition for the return that the marbles be exhibited free to all or at the same charge to all. Finally, the precedent argument: without going into the merits of other cases, the marbles are part of one of the most famous and beautiful structures in existence – standing for Greece in the eyes of the world. The marbles are clearly a special case: their return would set no precedent.

No one suggests that every artifact taken from Greece over the centuries should be returned. The problem is where to draw the line and one can only say that every case where the issue is raised must be considered on its own merits. It has already been shown that there are arguments both ways on the Venus de Milo. The removal of the Winged Victory was out-and-out theft. The only argument against returning the Aegina pediments is that the Museum of Sculptures in Munich is doing an excellent job in exhibiting them as the centerpiece of a fascinating reconstruction of the site. The frieze panels from Bassae do not have even that argument in favor of their retention. Certainly the arguments in favor of restoring the major temple sculptures seem unanswerable.