PHOTOGRAPHS BY TIMOTHY DEVINNEY / FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE JEWISH MUSEUM OF ATHENS

Many treasures that had been preserved over the centuries were suddenly eradicated in the twentieth century primarily during World War II by the Nazi regime whose aim was to annihilate not only the Jewish people but their culture. Nevertheless, throughout the world attempts are being made to collect the scattered heritage. In Athens the organizers of the new Jewish Museum have undertaken the difficult task of gathering together the surviving works and piecing together a historical picture of the once large but relatively-unknown Jewish communities in Greece.

For more than two thousand years Jewish communities flourished in various parts of what is Modern Greece. The largest and most famous community was, of course, in Salonica. The Apostle Paul on his travels (his First Epistle to the Thessalonians was written circa the middle of the first century) found a thriving community. It continued as a flourishing centre for many centuries, its numbers augmented by the Spanish and Portuguese Jews who arrived after the Spanish Inquisition. Salonica became famous as a centre of learning and its libraries were celebrated throughout the world; there was even an academy of poetry which produced a plethora of poets, musicians, and philosophers. Although other Jewish communities in Greece were smaller and less prosperous, they, too, had their collections of books — the keystone of Jewish life — and treasures.

Many of these communities have disappeared and with them family libraries, works of art, and historic memorabilia. Many individuals who survived the Holocaust emigrated abroad and those who remained behind, stunned by the events of the War, had little desire to begin the painful task of assembling the fragments of their cultural past. They tended to look to the future rather than the past. Today the Jewish Museum of Athens, under the direction of Nikos Stavroulakis, is amending this situation and rekindling an interest in the Jewish heritage of Greece. In a short space of time, Stavroulakis has assembled a valuable collection of ancient Judaica which is continuing to grow.

The project took shape late in 1977. The nucleus of the collection consisted of eight sacks, returned at the end of the war by the Bulgarians, containing personal possessions confiscated from Greek-Jewish concentration camp vic tims. They included items such as gold teeth, children’s identification bracelets, watches, rings, amulets and German dispatch notes. The museum thus began as an exhibition of the Holocaust as it affected Greek Jewry, with details of the numbers who died from each community.

To this initial, heartrending assemblage have been added other discoveries. An important find was a box, located in the synagogue of Ioannina, packed and ready for shipment to Germany. It contained a large number of Megilloth, scrolls of the Book of Esther favoured in many Greek communities as gifts to brides. The silver scroll cases, some with delicate filigree, demonstrate the high quality of Ioannina silver work, and the marriage of Greek craftsmanship and Jewish art. The collection from Ioannina and contributions from other donors have provided the museum with the most complete collection of Megiliothm the world.

The emergence of these Megilloth and their placement on public display, generated responses from other sources. Gifts began to pour in and other discoveries were located in the ruined synagogues and houses of the old communities. In the basement of a mosque in Rhodes, two Sephers — large scrolls containing the five books of Moses — were found. They had been kept there under the protection of the island’s Muslim community during the Nazi Occupation, while the Jewish community was decimated.

Maurice Sorianos, the President of the Jewish Community of Rhodes, presented the Museum with silver crowns and a Torah breastplate. In November, three more ancient Sephers were found in Patras, unique examples of Sephardic art. One from Crete is the only surviving legacy of the community of Heraklion which flourished until World War II.

Although the collection of fine ceremonial art and books is expanding, purely personal memorabilia of less historical interest retain a place in the Museum. They have come from all over Greece and include a number of exquisite religious and secular embroideries. One of the most interesting is a crimson scarf embellished with seed pearls which form the names of the angels Sanvai, Sansavai, and Smarangoff as well as Hil (misspelled as Hoi), one of the names of Lillith, the first wife of Adam, who in Jewish folklore is an evil spirit who attacks children. The scarf would have been worn by a mother after the birth of a child to prevent Lillith from devouring the infant. This is a beautifully preserved and rare example of the amulets associated with the legend of Lillith.

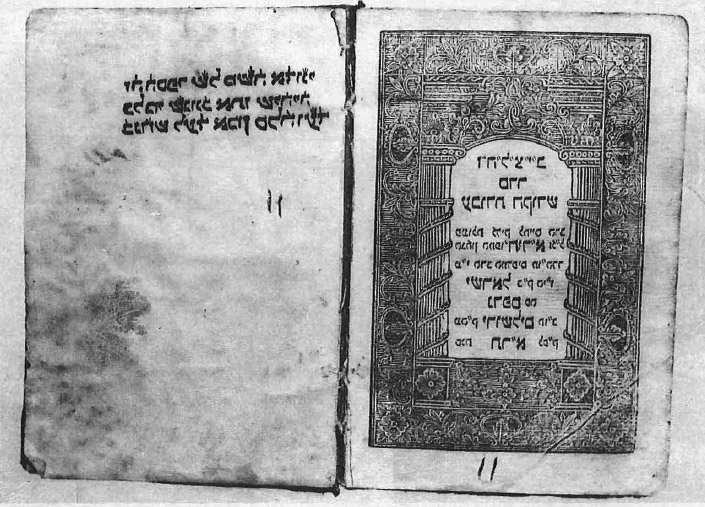

The Museum’s small book collection contains the first Hebrew book printed in Jerusalem, at the press of Israel Bak in 1841. It was discovered among several boxes of discarded books. Older books from the collection include a superb first edition from 1579 published by the Bragadini Press in Venice. They are a sad reminder of the thousands upon thousands of books destroyed in the Great Fire of Salonica in 1917, and then during the Nazi occupation. By the early sixteenth century, Salonica had its own presses but only four of the books printed there have been recovered by the Museum.

The Museum’s collection also reveals the folk customs and styles of the old communities. Although there is presently no space to display the fine costumes in the collection, there are interesting prints and nineteenth century photographs showing Jewish dress from various areas of Greece. Some folk items have been difficult to identify. One strangely-shaped object was finally recognized by an elderly grandmother as a spoon holder unique to the Jewish community of Corfu. Slowly the different styles and customs of the old communities are being rediscovered, identified, and preserved.

The Museum’s director is something of a Renaissance figure: a curator, writer, Byzantine scholar, teacher, and artist. He recently wrote a book on Greek Jewish cooking, and is currently illustrating a book of ancient Greek pharmacopoeia. Born in England of Greek and Jewish parentage, Stavroulakis completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, and holds a master’s degree in Islamic Studies from Michigan State University. While working on his doctorate in England, he decided to turn to painting and eventually settled in Greece. In 1967, he found himself in Israel during the Six Day War. In the post-war euphoria, he decided to emigrate to Israel where he completed his doctorate at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He has taught Byzantine art and archaeology and participated in excavations at the old Jewish quarter of Jerusalem. In 1972, he decided to return to Greece.

While restoring a number of old monuments at the request of the Jewish Community, including the Synagogue in Hania, Crete, and travelling around Greece photographing Jewish monuments, he became increasingly aware of the need for a centre where ‘all these artifacts could be assembled. With backing from The Central Boaid of Jewish Communities in Greece and the Athens Jewish Community, and assistance from the Jewish Memorial Foundation, the museum became a reality.

Although Mr. Stavroulakis now has an assistant to help catalogue the material, the Museum is primarily a one-man endeavour. Finding the pedigree and provenance of each item is a long and painstaking task. (An heirloom wedding dress from a woman in Salonica was finally identified as having come from Smyrna, where her grandmother originated.) Restoration takes considerable time. The Museum collaborates with other research centres and universities, and hopes eventually to establish its own research centre and archive, as well as a library and laboratory for restoration. In the absence of endowments, the Museum depends on donations to continue its work and to raise the funds necessary to compete with the market for Jewish items that are sold in Monastiraki and other shops. “Priceless pieces of Greek Judaica have been lost to us in this way,” says Stavroulakis. Nevertheless, the unique and valuable collection assembled during its brief existence augers well for the future of the rich history of the Jews in Greece.