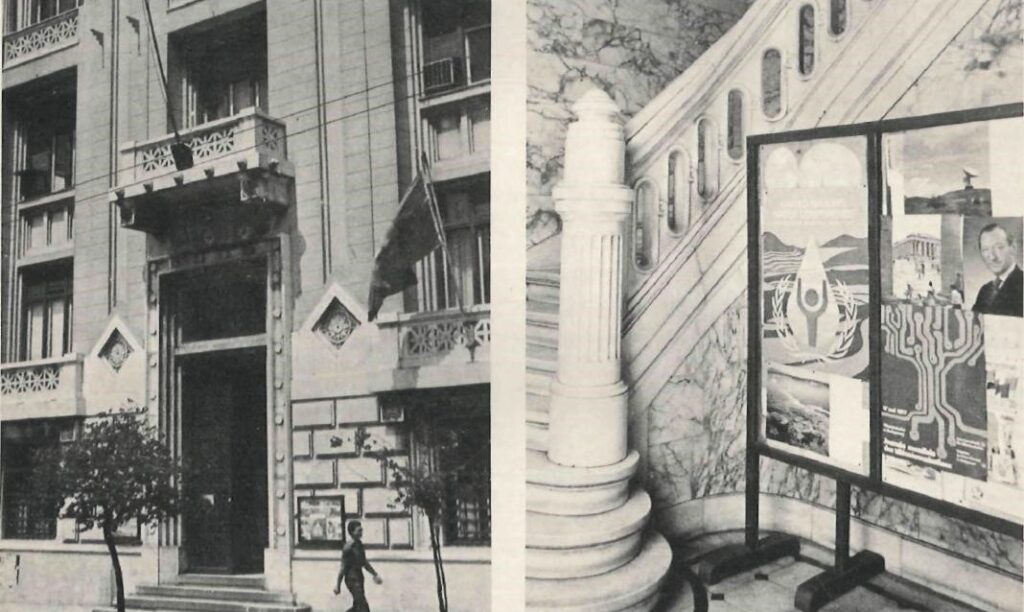

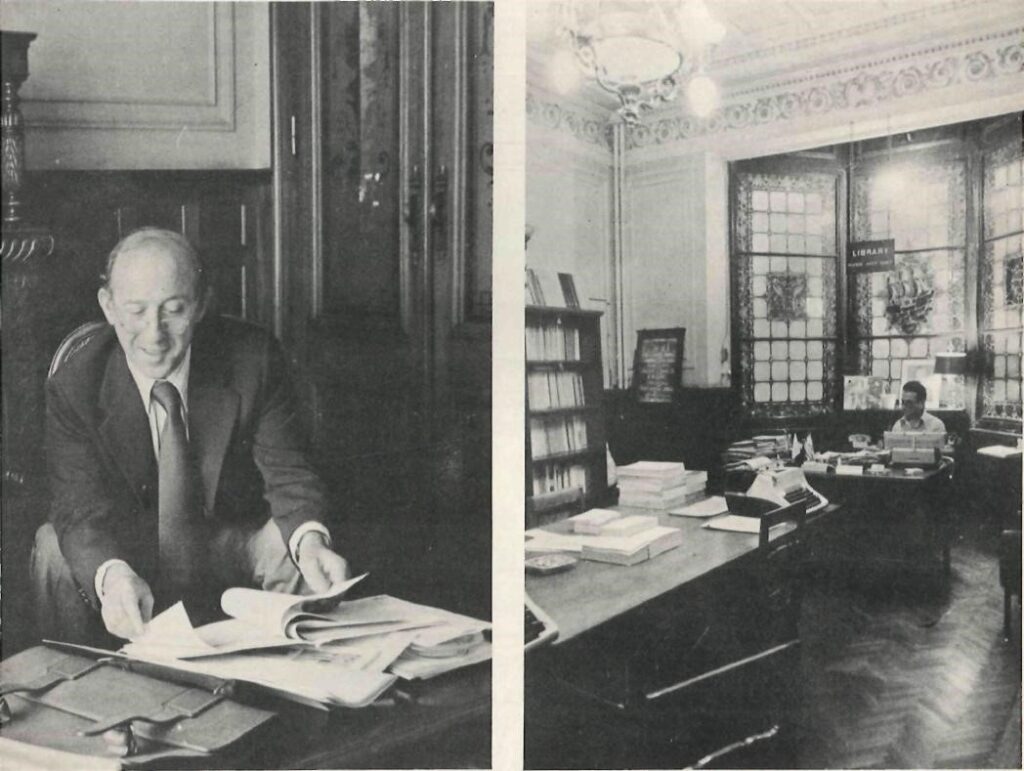

Beyond the imposing door of the quietly gracious building overlooking the National Gardens on Amalias Street is an elaborate marble stairway leading to the offices of the United Nations Information Centre. ‘This office, along with so many things in Greece, suffered from the dictatorship,’ explains the Greek-born head, Spyri-don N. Granitsas sitting in his stately wood-panelled office. ‘It was difficult for journalists or public officials to call on us, and difficult for previous UN administrators to travel to the provinces,’ he notes, partially explaining the reason for the lack of awareness here of the services available at the local UN offices. ‘As a result,’ he continued ‘very little information was disseminated about the UN’s work in Greece. Now there are no such restrictions.’

This year, for the first time, there will be a UN pavilion at the annual International Trade Fair to be held this month in Thessaloniki. ‘We wish to emphasize non-emotional issues and stress the diversity of the organization as an instrument of peace and development, dealing with projects ranging from narcotics to the protection of the environment.’ The purpose of the pavilion, which will be inaugurated by the UN’s High Commissioner for Refugees, Sadruddin Aga Khan, is to inform the public about the activities of the UN around the world and specifically the services available here in Greece.

That Greeks are often vague about the UN was demonstrated to Mr. Granitsas shortly after his arrival earlier this year when he went in search of a flat. After Mr. Granitsas told the concierge at one building that he was with the UN, the man telephoned the landlord and announced that there was a gentleman present ‘from NATO’. On another occasion, following a press conference held at the Centre to inform the public about a UN conference on pollution of the Mediterranean, a television news announcer declared that the conference was organized by the United States Information Centre in Greece. In an attempt to rectify this situation, Mr. Granitsas has appeared on local television and made official trips to the provinces. On a trip to Volos, for example, he discovered that a campaign was underway against drug abuse, a subject which several UN agencies — The Commission on Narcotic Drugs, The International Narcotics Control Board and The UN Fund for Drug Abuse Control — have been involved with for many years. ‘We sent them hundreds of booklets which w.e had just received from Geneva tha’t were very informative and helpful.’ While on a visit to Crete, he discovered that industrial zoning was the subject of a public controversy in Hania. None of the participants had thought to consult the UN Industrial Development Program in Vienna which has done many studies on the subject and could have offered expert advice.

The function of the Information Centre, which also covers Cyprus and Israel, is to channel the information emanating from the twenty-one organizations and fifteen agencies fanning out from the General Assembly. UN publications are available at the Centre’s library, as well as documen-taries and films. All the material is of potential interest to students, scholars, researchers, and industrialists.

There are two other UN offices in Athens: the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The three offices work independently and each has its own budget.

The UNDP, with its headquarters in New York, is under the direction of Mr. Haus Kamberg in Athens, the resident representative. In Greece since 1959, their offices are housed in the same building as the Information Centre. The UNDP is the major channel for technical advice and assistance which prepares the ground for investments and covers a large field ranging from agriculture and industry to education and public health. The UNDP also coordinates projects between neighbouring governments. A local example is the Vardar-Axios River Basin development project, a cooperative effort involving the construction of a complex system of waterways through Greece and Yugoslavia. For the 1972-76 period Greece received a total of $7,500,000. For each project one of the UN agencies — such as UNESCO, the World Bank, or the FAO — is selected as an Executing Agency. The recipient government meets, in most cases, over fifty percent of the costs, and provides local staffs, services and facilities.

At Skoufa 59 is the third UN office in Athens, that of the High Commissioner for Refugees, founded in 1951 and having its headquarters at the Palais des Nations in Geneva. (Greece has been associated since 1960.) The High Commissioner, elected by the UN General Assembly, is Sadruddin Aga Khan. His representative in Athens is Oldrich Haselman. The UNHCR helps governments to finance and coordinate refugee assistance and related projects. Refugees are provided with international protection, travel documents, counselling, permanent or temporary shelter, and assistance in settling here or abroad. Those arriving in Greece are accomodated at the Lavrion Reception Centre financed and administered by the Greek Government and for those wanting to settle here permanently, there are several housing projects in various parts of Greece. Over the years, approximately fifteen thousand refugees have settled locally, many of them in recent years from Cyprus. Some two thousand eight hundred refugees from Lebanon passed through Greece in the last year on their way to resettlement in the USA, Australia and Canada.

All of the UN offices in Greece maintain contact not only with government ministries but also with nongovernmental organizations whose aims and purposes parallel those of the UN. ‘Criticism is very important,’ explains Mr. Granitsas. ‘Media should be provided with any information they need and use it as a starting point for criticism.’

A graduate in law from the University of Athens, Granitsas continued his studies at Columbia University School of Journalism. He was on the faculty of New York University and has taught at the New School, Columbia, Harvard and the American University. After serving as foreign correspondent for such internalionl networks as the BBC, CBC and Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation, Granitsas joined the UN as a press analyst for the Secretary General in 1973.

‘We like to be discussed, criticized, to hear complaints, praises and suggestions about the UN,’ Mr. Granitsas says. Today the United Nations maintains offices only in Athens, but UN officials would like to see many more in the provinces as well. ‘The international character of this office should be emphasized in any possible way,’ he adds. ‘The offices in Athens are here to serve all nationalities.’