Photographs by Willard Menus

Still, there was something distinctive and familiar about it as it chugged into the bay of Lindos, its engine slapping away, guh-tonk, guh-tonk, in low speed, a sound that is as much a part of Greek island life as the bray of donkeys, the shrill cry of cicadas. Sure enough, when I steered my skiff over for a closer look, the dive boat turned out to be the Pegasus, out of Kalymnos, all right, and captained by George Lisgaris.

Exactly fourteen years ago, I had met Captain Lisgaris right here, in the bay of Lindos, and he had invited me out on the Pegasus to watch the sponge-divers at work. That first contact with the Kalymnians proved to be an important experience for me. The chance to watch the divers at work, taking turns plummeting into the hard-blue depths of the Aegean to tear sponges off the bottom, while the Pegasus circled slowly on the surface, under the white tight of the July sun, was a revelation, an inspiration.

Later I travelled to Kalymnos itself, one of the smaller but more striking islands in the Dodecanese chain, to investigate the life there, to meet and talk with old-time divers and deckhands, to delve into the history of Greek sponging. Kalymnos became a specialty of mine. I read everything I could about the island and its divers, beginning with the contemporary books of the late George and Sharmian Johnson, Australian writers who lived on Kalymnos in the early 1960s, and working all the way back to Oppian, Aristotle, and Pliny the Elder. Eventually I published some articles on the subject, describing the tough, resolute life the sponge-divers led, struggling to keep a long and noble human tradition alive in the face of encroaching competition from the artificial sponge industry.

Each year after that, Captain Lisgaris would show up in Lindos in early summer, usually with several other diving-boats from Kalymnos in tow. The small fleet would work its way slowly across the Aegean, ending up some months later at the prime sponging grounds off the coast of Libya, near Benghazi. Then, one year, the Pegasus failed to appear. A Kalymnian living on Rhodes reported that Lisgaris had sold his boat and emigrated to America, where he was diving for a living in the Gulf of Mexico. Now, suddenly, here was the reincarnation of Captain Lisgaris, bringing the Pegasus in toward shore, dropping anchor and pivoting round into the wind as the anchor bit and held, a nimble Greek sailor’s trick. We had a small, quiet reunion out there on the caique in the twilight, the sea turning dark purple around us and the day cooling off as the sun slid down behind the hills shouldering the harbour. On the main beach the tourist restaurants were closing down; the beach-boys were putting away the rental umbrellas and chairs, the onslaught of sun-hungry Swedes and Germans having ceased for a time.

Work aboard the Pegasus was not over yet. The sailors and divers were still trimming and cleaning the last catch of sponges, taking the big, black, pungent-smelling blobs and cutting the coral away, then trampling and foaming them with their bare feet. The sponges were then threaded on ropes and tossed over the side, to be further cleaned and bleached by the sea. Lisgaris’s son, a solid, chunky, sun-browned, sea-stained sixteen-year-old, began sorting out the various fish the divers had speared that day, a few kilos’ worth. They had also nabbed a couple of octopus and a karavida (rock lobster) in the course of their foraging along the sea bottom. Some of it would go into the communal fish stew, the rest sold to a restaurant on shore.

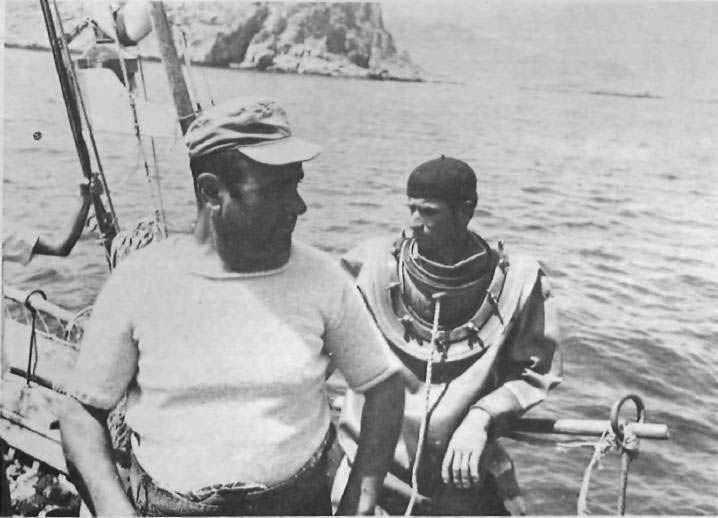

Over a plate of fooskas (a kind of mussel) and a pot of black coffee, brewed on a wood-burning hearth fashioned out of an old diesel-oil drum, I renewed my friendship with Lisgaris. He looked the same, a tall, powerfully-built man, with a dark, intelligent face engraved by hardship and exposure. Smoking one cigarette after another, he sat in his old, baggy clothes; his feet were bare, covered with salt stains and thick calluses.

No, he had not gone to America. A brother had gone off to ‘Fioreeda’ to dive for sponges. He, himself, should have gone to America, too, because there wasn’t enough money in sponging in Greece to make the effort worth it, but… Here he rotated his hand in a small circle, a gesture that can signify different things at different times: consternation, exasperation, punctuation. In this case, it said: Words can’t explain it all.

Anyway, after a lay-off of three years, he was back sponging again, running a boat with a full complement of divers and sailors. There was something special about this crew, he said. He was doing something new and different in order to stay in business. What was it? Well, I’d find out for myself when I sailed with them tomorrow, Captain Lisgaris replied obliquely.

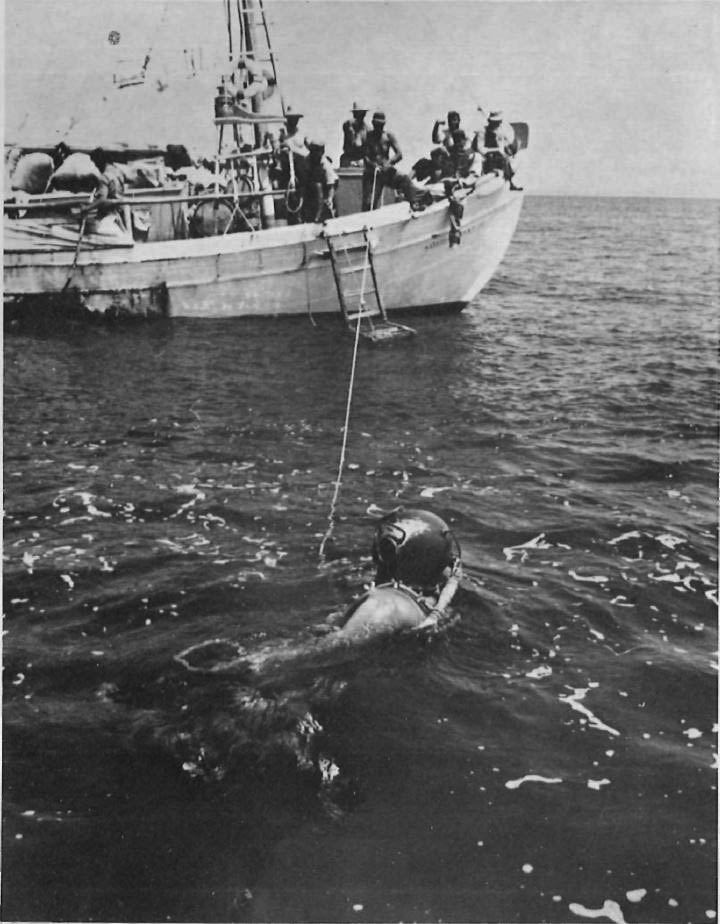

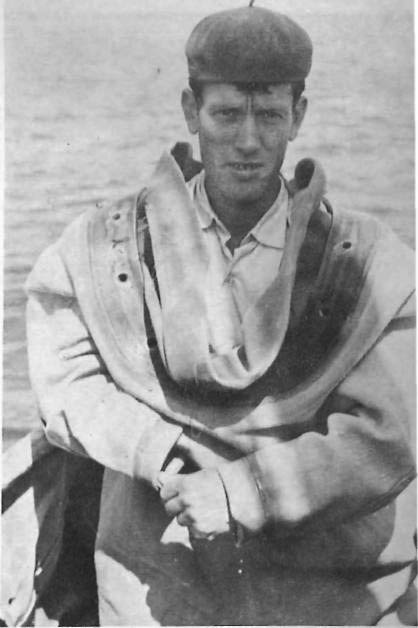

Γ he Pegasus was working the waters around the nearby islet of Pendanisi when I joined them, having arrived in my own boat, accompanied by a friend, John Phillipson. The rhythm of the work day had already been established. While one diver was down, another was suiting up, slipping into his inflatable suit, his lead shoes and weights, his bronze collar. A deck hand played out the air hose while another controlled the safety line tied to the diver, who was now twenty metres beneath the sea. The work went on quietly; too quietly, it seemed. No one was shouting or arguing, there was almost no conversation between the men. Since Greeks are normally voluble, this struck me as something of a phenomenon. It was not long before I learned why the atmosphere was so silent and strained. Half the men aboard the Pegasus were not Greek but Egyptian.

‘The Greek divers refuse to go out sponging any longer’, Lisgaris explained. ‘Those you see here are some old-timers who need a few more years of work to qualify for their government pension.’ (The magic number for a Greek diver is eighty — a figure determined by his actual age plus his number of years at sea— in order to be eligible for social security).

Arab divers on a Greek boat! In this part of the world, where Moslem and Christian are so often at each other’s throat, that was significant news indeed. We settled down to watch and learn how the experiment was working.

It didn’t take long to discover that the divers had split into separate cliques, one Egyptian, the other Greek, with the Greek deck-hands as a third entity. Lisgaris himself was caught right in the middle. He not only had to be leader, but mediator, placater, and translator. It was a task requiring all the tenacity, patience and diplomacy of a viceroy. The Arabs spoke almost no Greek, the Greeks equally little Arabic. It reposed a challenge, each order a problem.

Had the Pegasus been just an ordinary fishing boat, the problem would not have loomed so large. But this was a diving boat, carrying hard-hat divers who often worked at depths of fifty or sixty metres, staying down as long as half an hour to gather a bagful of sponges. They risked their lives during each descent, their well-being depending not only on technology—the smooth functioning of their equipment— but on human judgement as well: foresight, intelligence, experience, team-work. How could the Arabs expect to survive if even the simplest message sent down over the walkie-talkie had to be repeated four or five times before they understood and responded?

It seemed an impossible situation. Yet, despite the strain, the danger, the awkwardness, the misunderstandings and the arguments, things managed to work out well as the day progressed. The divers kept separate; they bitched a lot about each other, but without deep animosity or hatred. The Arabs and Greeks were certainly not in harmony, but neither were they at war. It would get better as time went by, Captain Lisgaris pointed out. They would get to know each other’s language. They would seek each other out as men. After all, he added, the Arabs were younger and less experienced divers. But they were learning, they were getting better every day, with a little help from his old greyheads. As for the Greeks, they would soon get used to living cheek by jowl with Arabs. They might even learn something from them too, because don’t forget, Lisgaris said, the Arabs were not only strong, able divers, but they were good men, too, decent people.

Watching all this, I could not help but be struck by the importance of world-wide economic and political factors in these islanders’ lives. Here was a perfect example of how the larger forces in life shape and affect a man’s destiny. Competition from plastic sponges was only one reason why most of the Kalymnians had been forced to give up diving for a living. They had also been disrupted by such an abstraction as the upsurge of nationalism in the Middle East. The new government in Libya had passed legislation, for example, which cancelled all former permissions and licenses to sponge. Foreign divers were now required to turn over fifty-one percent of their catch to the Libyan government, with the remaining forty-nine percent to be left behind under bond.

The Libyans said we’d be paid later for them,’ Captain Lisgaris said scornfully. ‘We’d get our money after they sold the sponges abroad. Do they think we’re crazy or stupid, or what?’

Thus, the Greeks had quit going to Libya, the site of the richest sponge beds in the Mediterranean. They were obliged instead to try and scratch out a living diving around the Greek islands. There had always been sponges here, but the beds were not large, having been depleted over the centuries. The sponges simply did not have a chance to grow. All that was left was small pickings, mostly second and third-rate product. As a result, hundreds of Kalymnians had been forced to give up their old way of life. The lucky ones, with families in America, could perhaps make it to Tarpon Springs, Florida, and find work there as divers. The rest were either obliged to join the Merchant Marine and sail to the ends of the earth, or emigrate to Germany and go to work doing hard labour in the factories of the Ruhr.

Γ he four Egyptian divers aboard the Pegasus were also historical pawns, victims of circumstances. Poverty had motivated them to leave their homeland, sail under an alien flag, in the company of strangers. They had signed on for twenty thousand drachmas per man for six month’s work. It was only half as much as the Greek divers were earning (it was this saving that enabled Lisgaris to launch the expedition), but for the Arabs it was still good money, more than they could expect to make sponging in home waters. Better to work for less with Greeks than go hungry.

Later, John and I moved over and talked with the Egyptians as best we could. How did they like working on the Pegasus? A non-committal shrug of shoulders. Were they worried about the lack of communication, the possible dangers the language barrier caused, the risk of the bends…?

Another shrug. ‘Mashallah. Allah will decide our fate.’ The work went on, slowly and steadily through the day, one diver leaping over the side, clutching his rope bag and sponge hook, another preparing for his turn beneath the sea. No one ate, the sun beat down, and the Pegasusrode round and round in a tight circle, her diesel engine kicking away, keeping time with the slow cry of the boy spooling out the air line: ‘Ikosi…ikosi-pende…’ Twenty…Twenty-five.

Γ he heat seemed to enclose us, the weariness and monotony of the work soon penetrated our bones, made us feel enervated, drained. There was no rest for Lisgaris. When he was not being a go-between, he was handling the boat, checking the air and depth gauges, reading a chart of the local waters, trying to find an unknown reef that might offer a more promising supply of sponges. No matter where the men seemed to work that day,nor how long they stayed down, they rarely brought up more than seven or eight good sponges each, most of these on the small side.

Finally, at about four in the afternoon, John and I decided we’d had enough. It was time to climb back in the skiff and journey back to Lindos. We said goodbye, first to Captain Lisgaris, then to the crew and divers. Leaving cigarettes and bags of fresh fruit behind as a present, we thanked them for their warm reception, their hospitality, and wished them good luck and fortune, wondering silently if this uneasy family of men would survive the summer well, and surmount their differences.

We tried to convey all this to the Arab divers, as best we could, Have a good summer, we said. May Allah the Merciful be with you. The Arabs came to the rail when we cast off, shouting and waving in unison: ‘Mas’salem… rabona yah’fasak.’God bless you my friends.

A few weeks later, I read the following news item in the local press: Ά 28-year-old Egyptian diver working on board a Greek sponge fishing vessel was drowned while diving off the coast of Karpathos on Saturday. The body of El Sayed Sabra Mohamet Aly was taken to a Kalymnos hospital for a postmortem. An investigation was opened by the port authorities.’