It is the aim of this ambitious project to integrate tourist facilities into typically Greek surroundings rather than to construct high-rise hotel complexes in the bland pattern of hotels around the world. This means that instead of building more Xenias (the Government-sponsored hotel chain), the new project will rebuild homes and other structures in the style characteristic of a particular area.

“A village standing out sharply on the steep slope of a mountain is a clear example of the unity of spirit, the unity of style achieved in true architecture. It is achieved not only because local building materials have been used, but because all the houses were brought into being by common life requirements. All this can only mean that the true work of architecture is not so much the result of what a single individual can achieve as the result of a collective endeavour.’

Aris Konstantinidis

The first village to be restored is Vathia in the Mani. Others to be developed according to this plan are Fiskardo on the island of Kefallonia; Zagoria in Ipiros; Oia, a village on Santorini which was destroyed by an earthquake in 1956 and never rebuilt; Mesta on Chios and Vizitsa in Pilion.

In his Athens office, Aris Konstantinidis, a trim man in his early sixties, explains how the project will work. He speaks quietly with the clear precision characteristic of his architectural drawings. The new philosophy of EOT is to restore scenic but depopulated areas for tourist and local use. ‘Local use’ refers to a plan which will encourage people to return to their villages. By handing back the restored buildings to their owners after ten years, EOT hopes that this will provide the necessary incentive to return.

If anyone can make the project feasible, Konstantinidis is the right man at the right time. Born in Athens in 1913, Konstantinidis has, in the forty years that have elapsed since he graduated from the Architectural School of Munich, become an architect of international reputation. He has designed private houses in Attica and on several islands including his own simple but spacious summer home on Spetses. Over the years, he has also worked for several governmental bureaus, ranging from the Ministry of Public Works (1942-1953) to the Organization of Labour Housing (1955-1957). He left Labour Housing after it became clear that he was not free to construct housing that would truly serve the needs of workers:

Ί wanted to build apartment complexes that had features such as play areas for children, but such ideas did not appeal to Labour Housing officials. Since they had paid for land they wanted to build as many apartments on it as possible in order to save money.’

From 1957 to 1967 he worked at the National Tourist Organization, where he was instrumental in developing the Xenia hotel chain. He personally designed the Xenia hotels in Epidaurus, Larissa, Igoumenitsa, Kalambaka, Paliouri in Halkidiki, Iraklion, Olympia and on the islands of Andres, Poros, and Mykonos. A frequent lecturer, Konstantinidis became a guest professor of architecture at the Polytechnic School in Zurich after he resigned his EOT position when the Junta took over.

When not involved with architectural projects Konstantinidis combines photography with his intense interest in anonymous Greek architecture. The result is that he has accumulated a collection of more than ten thousand photographs (mostly black and white) of folk architecture ranging from stone walls on Andres, to pebble patterns from the streets of Spetses. A successful exhibit of his recent photographs held in Athens last April was the latest in a long series of public showings in Europe and North America.

A Ford Foundation Grant in 1972 enabled this versatile architect to assemble a book of nearly three hundred of his photographs, in colour and in black and white, as well as sketches. It also contains his own commentary and a selection of illustrative quotations from Greek and European architects and from Greek writers such as Kazantzakis, Cavafis, and Seferis. Entitled Elements for Self-Knowledge, this study of anonymous Greek architecture is available in Greek, French, and English editions. The last was translated with great skill by the novelist Kay Cicellis. What makes this book of compelling interest, is that the author goes beyond architecture and photography to capture something of the spirit of Greece.

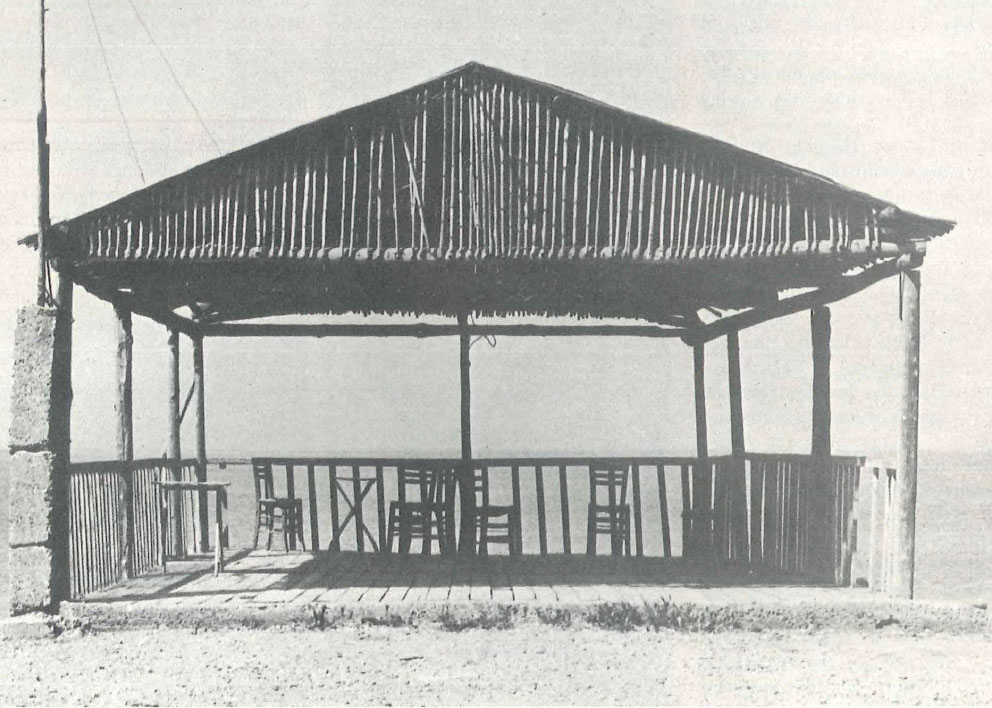

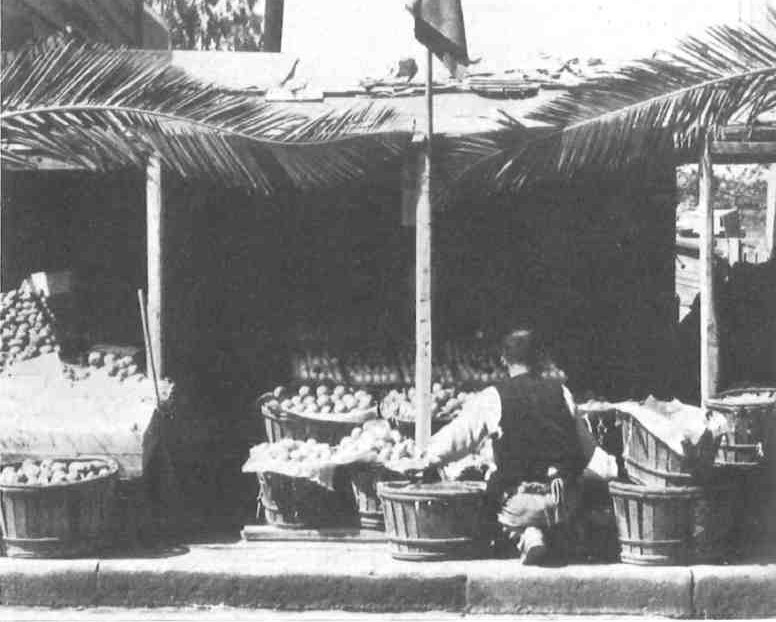

Konstantinidis has devoted a lifetime to the study of Greek architecture, from its simplest to its most complex forms, from the Bronze Age to the present. He feels that true Greek architecture has always conformed to its environment. This means that it is built to the scale of its landscape. (One has only to think how right whitewashed island chapels look in the context of sea and rock to know what Konstantinidis means — ‘clean-faced, clear-eyed’ as he describes them.) It also means that true architecture must be thoroughly attuned to its climate. Greeks have always lived out of doors or in the semi-outdoors. Fashions change, but authentic Greek architecture remains the same. It is due to the existence of this particular climate that a seaside taverna with its bamboo covering and supporting poles is built on the same pattern as the Parthenon. In respect to both structures, Konstantinidis writes,’The more genuine and contemporary a building is, the more it looks as if it has always been there, from time immemorial.’

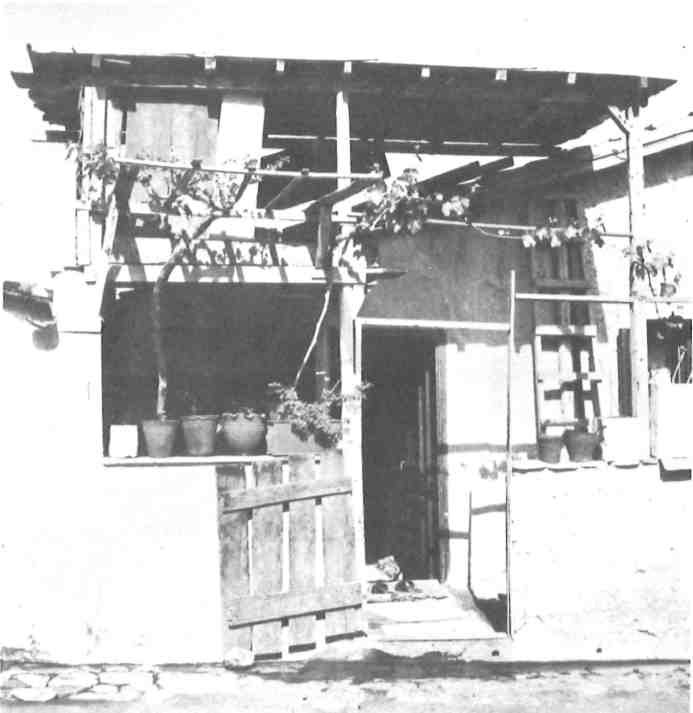

One of the most fundamental designs in Greek architecture, Konstantinidis emphasizes, has been based on the ancient inegaron. The megaron consisted of a main structure with a porch in front and an enclosed courtyard. Thus, Konstantinidis argues, the shacks constructed in the Athens area by the hundreds of thousands of Greek refugees from Asia Minor who poured into Greece after 1922 are ‘the most authentic architecture fashioned by the modern Greeks.’ Like Mycenean palaces, these huts — fashioned from whatever materials could be found — consist of an enclosed area (domatio), porch (apostilo), and yard (avli).

‘Why did they build this way?’ Konstantinidis asks. ‘Did these refugees know about megarons ? Had they studied such architecture? No! The answer is the climate. Greeks live out of doors and so they construct homes suitable to the Mediterranean climate.’

In this connection Konstantinidis particularly emphasizes the unique quality of Greek light. He expands our concept of architecture by suggesting that ‘whatever is modelled by the light of the sun is also architecture.’ The Greek sun lends blinding definition to whitewashed structures and strength to the subdued traditional earth colours that come from natural, native sources. Konstantinidis abhors the use of plastic paint as being wholly alien to both the light and the landscape of Greece. The brilliance of this light and the spareness of the landscape have always given strength to form and economy to detail.

Certain forms have kept reappearing in the long tradition of anonymous Greek art. There is a striking resemblance between the trident of Poseidon and a church candelabrum, between the ancient tripod and an iron kafenion table. Of the latter, with its circular top and three curved legs made steady by a triangular brace, Konstantinidis observes: ‘Now there are only a few left here and these, abandoned and rusty. Yet they were so right, so in tune with the Greek landscape, simple and modest, organic both in form and function, like the candelabra in country chapels.’

Konstantinidis’s conception of anonymous architecture is superbly exemplified by his project in Vathia. Yet it presents a special challenge to the architect as it is not in many ways typical of a Greek village. Crowning a mountain in the desolate landscape of the Deep Mani, Vathia was built under social conditions that no longer have any relevance today. In true Maniot fashion, each house is a tower which reflects an era when families lived in fortified units to defend themselves during lengthy blood feuds. Despite its foreboding atmosphere in winter, this ghost town is beautifully situated to capture cool summer breezes, and it has a commanding view of mountains and sea, which rivals that of Delphi.

There are plans to complete the renovation of twenty towers within the coming year. ‘The Tourist Organization does not buy the towers] Konstantinidis explains. *They are leased to us by the owners for a ten-year period. During that time, besides rebuilding the property, we will pay a token rent—say a thousand drachmas a month — and at the end of the period we will return the developed property to the owners to do with as they wish. At this point agreements with most of the owners of the towers have been arranged, and we are now nearly ready to begin. All the accommodations will be simple and inexpensive, designed for the tourist on a budget. We’ll fix up rooms, tavernas, stores… but we won’t bring in juke boxes. A bed, clean sheets, a shower, that’s all!’

The Mani has been chosen as a test area because, while it is scenic, it has also been one of the most isolated and financially deprived areas of Greece. The project could boost the area economically. The general plan calls for developing not only Vathia’s tower-homes, but also many others scattered around the cliffs and shores of the Mani. Restoration by itself, however, is not enough. ‘Vathia, for example, has nc paved road leading to it, no electricity, no water/ Konstantinidis explains, ‘so we must begin by providing these costly essentials.’

If the experiment succeeds, tourists will be able to enjoy a more truly Greek experience, at moderate cost, in a rugged yet stunningly beautiful setting. Even more important is the hope that the natives will return to settle in such areas.

Konstantinidis believes that it is a difficult and complex problem to get people back to their villages. It takes more than architects to improve the. human environment. It needs the combined efforts of politicians, sociologists and the people themselves. The villages must be made viable in practical as well as aesthetic terms. It is a lofty aim, but it is not without criticism, even from those within the Tourist Organization.

‘I’m not convinced it will work/ says Konstantinidis, ‘but who knows, it may!’

There is also the risk that others less idealistic will exploit the Mani as just another tourist area, with the result that gaudy eyesores will crop up within view of the reconstructed towers, blaring rock music into the early morning from overpriced discotheques.

Although much of Greek architecture has remained unchanged for centuries, Konstantinidis’s work at the Tourist Organization has made him painfully aware of the rapid alterations in Greek life. The influx of tourists increases every year. At the present rate, what will Greece be like in ten or twenty years?

‘I’m afraid everything works for the worst,’ Konstantinidis states sadly. ‘While the Government tries, on one hand, to improve the quality of tourism through projects like the Vathia program, on the other hand, they grant permission for industrialists to develop a shipyard and cement factory in the beautiful natural bay of Pylos.’

Konstantinidis believes that if tourism is not controlled soon, Greece will quickly become a wasteland of high-rise apartments and hotels stretching along polluted waterfronts. It may become another Costa Brava. The Junta must receive much of the blame for this situation, he believes, since they encouraged rapid and unchecked touristic expansion in order to help balance the budget. The problem today is not technology itself, whose products, are desirable, but it is the way in which technology disregards environmental and human needs. Tourism will always be important to Greece, but it must be recognized as a mixed blessing.

‘True architecture makes beautiful ruins,’ writes Konstantinidis, quoting Auguste Perret. The architect believes that Vathia makes good ruins because it just gets old along with the landscape, along with its inhabitants. ‘The mark of a good building,’ he repeats, ‘is that it will look as if it was always there, as if it was meant to be there.

‘In the final analysis, a true work of architecture should be temporary if it is expected to function as a truly effective instrument for living…’

So the Vathia project is, ultimately, a compromise in his eyes.Tie believes that old buildings should be preserved but that they should not be idolized. To rebuild a tower-house or an entire village can simply be a false evocation of the past. In the past the inhabitants of the Mani had to live in towers to protect themselves; for tourists and Greeks to live in them today is a form of nostalgia.

True Greek architecture, he believes, does not depend upon imitating the past. It should be a dynamic development, within the tradition which expresses contemporary reality and awareness. Its highest purpose is to find the truth of a place.

‘After all, do I have to wear a fustanella to prove I am Greek?’