Photograph by Makis Skiadharesis.

Part Two: The Greek Portrait

Friar was born on the Turkish island of Imrali (Kalolimnos) in the Sea of Marmara but had emigrated to the United States at the age of three. He had never lived in Greece but had always considered it to be his spiritual home. His homecoming had to be postponed for a year, however, while he fulfilled a teaching commitment to Amherst College.

He speaks fondly of the lovely New England town, the home of Emily Dickinson whose poetry he considers, heretically, to be superior to that of Sappho. He speaks with enthusiasm about the college and his students whom he judges to have been among the best and the brightest he has known. They were mature students who had just returned from the war and knew what they wanted from education. It was at Amherst that Friar became the teacher and friend of James Merrill, the poet who has since won the National Book Award and the Bollengen Prize in Poetry. He remembers Merrill as a shy young man who one day handed him a pile of poems in the school cafeteria. Having been deluged over the years by the indifferent work of many self-styled geniuses, he set aside Merrill’s poems for a while only to be astonished by their quality on first looking into them. He immediately got in touch with Merrill and began to teach the young man all he knew about the craft of poetry.

Merrill was soon transforming the exercises into beautiful poems, many of which he wrote to his teacher and about his teacher. One of these, The Black Swan, provided the title for a limited edition of Merrill’s first verse published in Greece in 1946 and dedicated to Kimon Friar. The cover was designed by Ghika. Friar smiles as he recalls that he had ‘Not For Sale’ printed on each copy so that they would become what they are today: collectors’ items.

Merrill, whom Friar refers to as his second, brilliant pupil — John Malcolm Brinnan having been the first —was the son of one of the founders of the brokerage house, then called Merrill, Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Beane, and held a trust fund worth millions. Merrill, soon to graduate, was torn between his family’s expectation that he would enter his father’s business and his own wish for a career as a poet. Friar insisted that it would be criminal for a poet of young Merrill’s talent to become a businessman. The young man chose poetry and confronted his father who, though disappointed, did everything he could to help his son’s career. Soon after Friar arrived in Greece in 1945, Merrill travelled from America and joined him. He has maintained a home in Athens ever since.

His commitments to Amherst completed, Friar set out to rediscover his roots. Travelling on a Liberty ship, he arrived in a Greece which had just emerged from World War II, only to be plunged into a horrendous civil war.

Despite the turbulence around him, Friar discovered here an inner peace: ‘When I entered the harbour at Piraeus I felt in an intense, mystical, and very real sense that I’d come home. I suddenly realized that I had been a stranger in America.’ I ask what he means by this and he gives as an answer the use of hand gestures. Without being conscious of it, he had always talked with his hands and body, a manner that seemed strange to Americans. In Greece it was not peculiar: everybody expressed himself in this way.

Photograph by Aris Konstandinidhis.

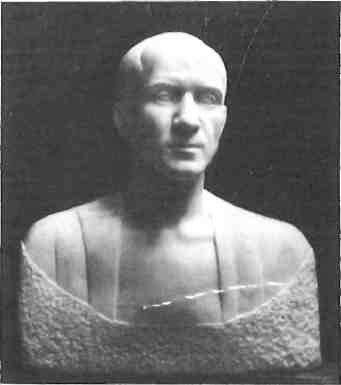

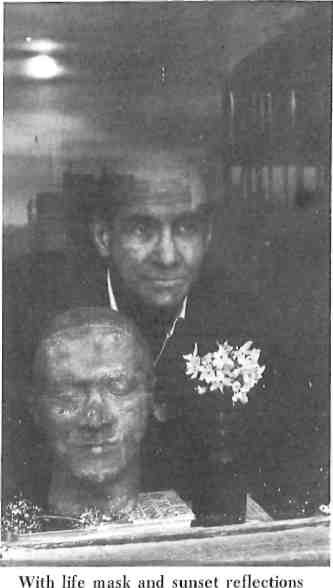

His apartment in Athens today is filled with the memorials which have become the symbols of his life. There is the life mask from his youth made during his ‘friendship’ with Keats, his portraits in oil by Tsarouhis and in marble by Natalia Mela, the Medusa made by Ghika. A wall is covered with photographs of friends: Kazantzakis, Sikelianos, Seferis, Ritsos, Elytis, Vasilikos, Samarakis, Gatsos, Embiricos, Xarhakos, Kanellopoulos, and the Papandreous, father and son.

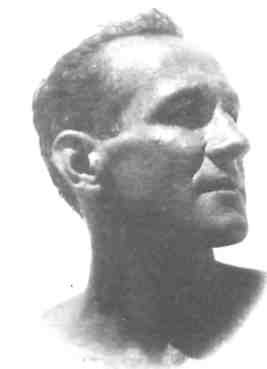

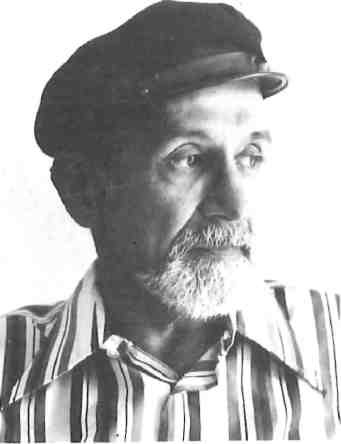

Friar is tanned and lithe. In a photograph taken in 1973 when he had grown a beard, he resembles an old sea captain — perhaps much like his maternal grandfather who plied his caiques between Alexandria and the Crimea in the last century. He likes this picture, but in person Friar looks much younger.

Friar Pauses, searching for the words that will best describe his first Greek experience. Until that moment he spoke with the hypnotic power of a well-rehearsed Ancient Mariner. Now he finds it difficult to select a point of departure. We both observe that distant memories sort themselves out easily but recent experiences are confused: one is unable to view them objectively. Friar seems to have, indeed, separated his life into halves — into a ‘duality’ as he would say. The American experience was sealed off when he returned to Greece. The Greek experience is now so much a part of him that he finds a simple chronological account an ineffective means to expressing what has happened to him. We speak of Friar the translator. He began, he notes, with many advantages. He was a poet and had been a teacher of the craft of poetry. He has — always — at his conscious command, all the techniques he has taught his students: the use of metre, rhyme, rhythm, imagery. He had first to improve his Greek, however. He frankly admits that his command of his native tongue was poor when he first arrived. He had studied ancient Greek in college but it was through his translations and his conversations with the poets that he learned modern Greek well.

His fascination with modern Greek poetry was such that he translated the works of thirteen poets in two years. Those whose works he had selected, however, were a special group, primarily Surrealists and Symbolists, for whom he felt a special affinity. Ί hate cliques and so I decided not to publish my translations until I had a more representative collection of modern Greek poetry’, he explains. Friar did not realize that his project would become so all-consuming. In the ensuing twenty-six years he translated eighty-five poets.

The anthology that was planned in the late forties materialized as a book only last year. Modern Greek Poetry and its sequel Contemporary Greek Poetry, on which Friar is presently at work, are landmarks in translation. Together they are of much wider significance than his translation of Kazantzakis’ Odyssey because they introduce to the English-reading public the entire spectrum of modern Greek poetry from Cavafis to the present. The first volume, Modern Greek Poetry, a choice of the Readers’ Subscription Club, contains, as well, a 130-page introduction, a definitive essay on translation, and almost a hundred pages of notes. Friar’s work serves not only as an anthology but also as the most thorough textbook on modern Greek poetry in translation. It is a massive accomplishment.

I ask if he had ever considered simply editing such an anthology, delegating the translations to various contributors. He answers that he most certainly would have done so had he known the time and soul-consuming effort his work would eventually involve. He had committed himself to the project, however, and resolved to complete the task he had so lovingly begun. In the future he will collaborate with others in translating and editing the works of several poets.

Friar has had the immense advantage and good fortune to work with all but four of the poets whose works he has translated. Cavafis, Kariotakis, Ouranis, and Sarandaris had died before he began translating their work. All of the other translations were made in cooperation with the poets. He dedicated his anthology, ‘To my collaborators, the Greek poets.’

In his essay on translation included in the anthology, Friar writes that translation is the urge to go beyond and over, beyond lands and nations and times and languages, proceeding under a million guises and disguises toward that ideal realm, that Ithaca, that universal language longed for but never attained, a spiritual if not a physical communication. No translation is timeless no matter how universal the language may be. New ones are needed as cultures and languages change. Good translations are thus blood transfusions, often giving life to what was on the point of dying, he writes. Like transfusions, they must be continued if the work is to live.

Friar reaches for another book and hands it to me. It is The (Diblos) Notebook by James Merrill. He explains that he is cast as Orestes in Merrill’s novel and that the story is based on his relationship with a Greek woman whom he met on Poros in 1948. After her husband’s death that very year, she told Friar it had been his wish that Friar stay at his estate, and she asked him to live and work at their villa for as long as he wished. He accepted and stayed there for two years in the gardener’s cottage. Friar remodeled and named the cottage ‘The Medusa’ after a collage of that gorgon made for him by Ghika which was imbedded into the wall above the lintel. On Poros he translated many of the Greek poets. Grateful to the widow for her encouragement and help, he invited her to join him when he returned to America to resume teaching in 1951. Merrill’s book is primarily about their relationship.

Can the novel be read as an accurate account of those years? ‘Of course not!’ Friar exclaims. ‘It’s a novel, a notebook, a roman a clef in which the author discusses the relationship between fact and fiction. I recognize myself in it, of course, but as though I were looking into one of those distorting mirrors found in carnivals. I don’t much like what I see, not that mask of me, but I cannot possibly object, first because an author has the right to do anything he pleases with his material, and secondly because it is beautifully conceived and written. Gore Vidal has distorted me much more by using parts of me in the character ‘Friar Andrews’ in a recent novel, Two Sisters, in which he mercilessly lampoons the two Kennedy sisters and Anais Nin.’

I borrowed Merrill’s book to read. Much of Orestes’ character, as presented by the narrator, is negative. Many passages seem perceptive and, to me, accurate. Merrill writes, for instance, that Orestes’ tastes run to Michelangelo, the monumental, the metaphysical.

The Odyssey, a Modern Sequel, is Nikos Kazantzakis’ verse epic about contemporary man’s search for meaning and purpose. Kazantzakis begins where Homer left off. Odysseus is restless and soon wearies of the peaceful domestic life of Ithaca. He sets sail in search of freedom and God. He travels to Crete with a new crew and Helen of Troy who abandons Menelaus in favour of new adventures. After taking part in a revolution which destroys Knossos, the wanderer embarks for Egypt with his crew but without Helen. There he finds a decadent civilization where revolutionary forces oppose the Pharaoh.

Odysseus escapes with a number of refugees and journeys through Africa to the source of the Nile. There he establishes an ‘ideal’ city, elements of which show the influence of Plato’s Republic, St. Augustine’s The City of God, and More’s Utopia. The city is destroyed by an earthquake, however, and Odysseus becomes a renowned ascetic. Finally, after travelling south through Africa and sailing out into the ocean, he reaches the regions of the South Pole where he dies. Kazantzakis introduces many symbolic characters along the trip who represent Buddha, Christ, Don Quixote and others who teach Odysseus much. He ultimately breaks away from each in order to preserve his quest for God whom he defines as ‘wide waterways throughout man’s heart.’

I had heard Friar speak before about his working friendship with the Greek writer. I was curious to learn, however, how he had met the author of The Odyssey and how he came to decide to translate the epic.

It began with the artist Ghika at his home on Hydra. Ghika had such a strong affection for Kazantzakis’ work that he planned a series of forty drawings to illustrate passages he had selected from The Odyssey. Kazantzakis had written a prose summary of the entire epic to combine these selections. Friar had heard very little about the bold, Greek writer whose reputation in his own country rested, at the time, mainly on his travel literature.

He read the forty selections and the summary, and was so impressed by them that he began to translate them and the summary into prose.

He first met Kazantzakis in the summer of 1951 at a youth hostel in Florence, Italy. ‘We were eating on plastic trays in the garden’, Friar remembers, ‘and it was so dark we could hardly see each other’. After they had talked for a half hour or so Kazantzakis, impressed by Friar’s perception, asked if he had in fact read all of his works. When Friar told him that he had read only the forty selections of The Odyssey, those chosen by Ghika which he had translated, Kazantzakis exclaimed that he had never met a man in his life who understood him so well. Kazantzakis’ words proved to be true Friar speaks of the ‘amazing rapport’ that existed between them from the start and continued until the poet’s death five years later.

Although Friar published the prose translations in various periodicals when he returned to America, in the autumn of 1951, he did not have any immediate plans to translate the entire Odyssey, He was preoccupied by his work at New York University in Washington Square where he was teaching the writing of poetry and modern American and British poetry. At the same time he was conducting a radio programme sponsored by Grove Press called ‘Magic Casements of Prose and Poetry’. The title words ‘magic casements’ from ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, were most appropriate to Friar whose first view of the world of poetry was glimpsed through the verse of Keats.

While in New York Friar had the chance to see old friends and through one of these, Arthur Miller, he made a new acquaintance: Marilyn Monroe. Thinking of Miller’s drama, Afrer the Fall, which is about the playwright’s relationship with Monroe, and of Norman Mailer’s recent laboured analysis of her, I ask Kimon how he remembers her. He found the relatonship between her and Arthur to be an attraction of opposites: he, the labouring, conscientious artist — the intellectual, involved with and sharing in the guilt of modern man — she, so unconscious of her artistry that no one has been able to define it — a beauty ravaged by the guilt of others, symbol of carnal knowledge, yet remaining, herself, innocent. Kimon remembers Monroe as a woman of wit and intuition, if not one of knowledge and intellect. ‘She was neither moral nor immoral, but moved and lived with the innocent amorality of a pussy cat. And’, he adds, ‘she did indeed have a vivacious and voluptuous beauty’.

At the Off-Broadway theatre, Circle-in-the-Square, Friar organized programmes similar to those at the Poetry Centre but with an emphasis on drama. Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, Arthur Miller and Lillian Hellman, among others, read from their plays, scenes of which were frequently acted out by the theatre group. He presented operas, musicals, films, jazz, poetry readings.

After a year in New York he accepted a teaching position at the University of Minnesota in Duluth. Surely Duluth was an anticlimax after the excitement of New York! ‘No!’ he remonstrates. Ί have never been made unhappy by any place. No place has ever disappointed me. The great varieties of life and experience that fascinate me can be found anywhere on earth, even the North or South Poles. Of course, Greece is for me the one place, because it is out of this world.’ At this time, he was an active reviewer, contributing articles to The New York Times, the Saturday Review and the New Republic. With the latter he was also a contributing member on its editorial board.

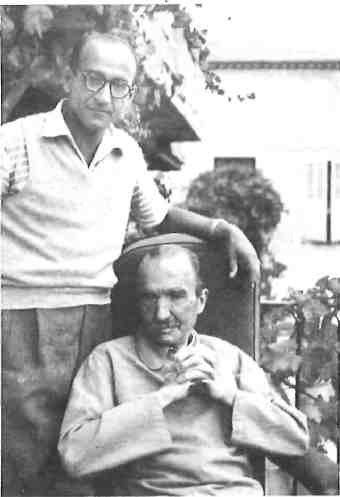

Photographed by Helen Kazantzakis Antibes, France, 1954.

The Odyssey project became a reality when the publisher Max Schuster visited Kazantzakis at Antibes, in 1953. After the great success of Zorba the Greek, Schuster made the trip in order to sign up the Greek writer for further translations of his works. While in Kazantzakis’ study he asked about the mammoth first edition of The Odyssey which the poet-writer kept on his writing table. Kazantzakis explained that of all his books, it was the one he considered his masterpiece. Schuster, who, from childhood, had felt a love for Homer, was fascinated by the new epic. Kazantzakis read him parts of his poem. Schuster was enthusiastic, even though he could not understand Greek, and insisted that the book be translated. But who could translate it? Only one man in the world, replied Kazantzakis. ‘Where is this man to be found?’ asked Schuster. Ίn Duluth, Minnesota!’ — replied the Greek writer.

Friar was, of course, happy to be chosen for the task, but he was not at first sure how a translation of The Odyssey should be done. He enjoyed his life as a university professor and considered working on a prose translation during summer vacations. After spending the summer of 1954 with Kazantzakis in Antibes, he decided on a verse translation.

The Odyssey consists of twenty-four books or chapters. In Antibes, Friar with the Greek writer’s help, made a translation of Book Six into prose and parts into several verse forms as well. The results strongly suggested that verse was the only honest solution to the problem of translating Kazantzakis’ rich imagery, but Friar was uncertain. He sent copies of the translations he had made thus far to friends such as Gore Vidal, Tennessee Williams, Archibald MacLeish and Arthur Miller, as well as to T.S. Eliot. The answers were unanimous: The Odyssey should be translated into verse, into iambic hexameter. The decision was made.

Friar was now confronted with the fact that he would have to devote all his time to the project. If he worked at the translation only during his summers, it would take ten or more years to complete. A Fulbright Fellowship and a small stipend from Schuster, however, enabled him to sail from France and to return to Greece.

Ί lived very, very simply indeed’, says Friar of the four years he spent on the epic. He had all of Greece in which to translate, however, a fact that should inspire even the most insensitive souls to poetry and a zest for life. He travelled throughout the Peloponnisos on a Lambretta scooter, stopping in villages and writing on cafe tables surrounded by his dictionaries, notebooks and an edition of The Odyssey. He followed his pattern of work while wandering — like Odysseus himself — through many Aegean Islands to Crete, the Ionian Islands and, of course, to Ithaca.

Was it difficult to translate without. being near Kazantzakis? Friar felt that the four months he spent with the author in 1954 provided him with an understanding of the entire epic, both its scope and language. Every day from seven in the morning until late afternoon, Kazantzakis read The Odyssey while Friar noted down unusual words and difficult passages. Ί was fortunate because my Greek was not sufficiently accomplished for me to realize how strange the language of The Odyssey really is in terms of the Greek language. I accepted it as it was!’

The Odyssey presents many problems even to those who know the Greek language intimately. Many have enjoyed The Odyssey more in English than in Greek because in his translation Friar has kept to a simple idiomatic English vocabulary which captures the spirit of the original without attempting the impossible — finding English equivalents for Kazantzakis’ idiom based on an extreme form of demotic Greek, containing many words of the peasantry not found in any dictionary. Speaking of the man, Friar continued. ‘The thing that impressed me most about Kazantzakis was that he was a man of great complexity who knew many languages, who had immersed himself in almost every major intellectual movement of the twentieth century, had travelled in many parts of the world, had written many novels, travel books, dramas, poems and translated fifty books. Yet he was the simplest man I ever knew. He had the simplicity of deep water, very deep water. I was never so moved by the presence of simplicity and genius as I was with Kazantzakis and this is what I loved about him.’ As he says this, Friar is so possessed by the spirit of the man that one imagines seeing him reflected in his eyes.

Friar has over a hundred letters from Kazantzakis, whose books occupy several shelves in the living room. Each of these has a personal inscription from the author. He plans to write a book based on their friendship and collaboration. Kazantzakis once wrote him saying that if he had ever had a son, he would have wanted him to be Kimon. Of this Friar is immensely proud. In fact, Kazantzakis had no children and thought of his books as his offspring.

Opening his copy of Zorba, Friar translates the inscription To my dearly beloved poet and friend and ‘harokopo’ Kapetan Kimon Friar, who, if Zorba had known him would have acknowledged him as his son, as a true ‘zorbopoulo’. Signed, ‘egho ο hartopondikas’. Friar explains: harokopo means playboy; zorbopoulo, cub of Zorba; Kapetan, skipper; hartopondikas, bookworm.

He speaks of Kazantzakis’ unselfish concern for others. As an example, Friar refers to a serious accident he suffered on his scooter in Greece.

Kazantzakis had warned him that scooters were dangerous toys and that if he wished to commit suicide, he should at least have the kindness to wait until he finished translating The Odyssey! Friar took no heed of this advice and one afternoon near Xilokastron, swerving to avoid a donkey, he collided with a truck. He was taken to Evangelismos Hospital in Athens with a broken, right thigh-bone and a cracked skull.

‘When Kazantzakis heard about this, he sold his house on Aegina and sent me money. I felt deeply moved by this generous gesture of his, but I sent the money back right away, like a true son of Kazantzakis, even though I was desperately poor at the time and had to stay in a room with eighteen others, three of whom died before my eyes. The fact that he sold his house for my sake, however, meant a great deal to me.’

Though he worked by himself on The Odyssey between 1954 and 1957, he corresponded regularly with Kazantzakis. After the summer of 1954, which they had spent together, they met on two occasions. The first meeting took place after Kimon had reached the halfway mark. Kazantzakis suggested they meet in Bled, Yugoslavia, high in the mountains near the Austrian border. The author chose Yugoslavia because he had book royalties due him there which could not be used outside the country. He was to spend a holiday while working. Friar remembers that month not only for the valuable help Kazantzakis gave him in revising his translation but also because they had time to be alone together, to talk and to hike in the surrounding mountains. They continued their discussions very often until late at night. Helen, Kazantzakis’ second wife, was in Crete watching the filming of Jules Dassin’s, He Who Must Die, a film based on her husband’s novel, The Greek Passion.

They met again in Antibes in May of 1957. It remains particularly vivid in Friar’s mind, because it was their last. Kazantzakis reviewed the whole translation and not only approved it but wrote him that the translation had as much merit as the original and often surpassed it. Kimon notes this as typical of Kazantzakis’ generosity. When Friar left Antibes, the man whom he had come to love as his spiritual father, as a poet and a friend, embraced him and wept convulsively. ‘He was a man who hardly ever cried in his life’ Friar reflects. He asked Helen why her husband had broken down in such a way. She replied that he had a strong premonition that they would never see each other again. Kimon then left for America while Kazantzakis went to China. It was his last journey.

He who had written so intensely of man’s struggle in the face of death, died himself in October of 1957.

Γ HATE cooking!’ Kimon Friar JL calls out from the kitchen, on my next visit to his apartment. The living room was filled with the music of Handel and the hearty odor of baking stuffed eggplant and squash. ‘So when I have to,’ he adds, Ί cook something that will last for a week!’

He clears away a clutter of books and manuscripts and sits down to continue the story of his translation of The Odyssey, a Modern Sequel.

‘It never occurred to me that it would be an immediate success. I thought like Joyce’s Ulysses, it would take twenty years to be acknowledged’.

Thinking of the novel as being the most American of literary genres, I was curious to know how an eight-hundred page epic poem by a Greek could be so attractive to Americans. He laughs and compares Kazantzakis’ work to the Mississippi River, the Empire State Building, the Grand Canyon. ‘The epic has the scope and size Americans appreciate. After all, Whitman’s Leaves of Grass is meant to be one poem.’ He believes that Kazantzakis’ daring philosophy which is most lucidly stated in The Saviors of God (also translated by Friar) appeals to American youth. As proof he happily informs me that The Whole Earth Catalog identifies The Odyssey, A Modern Sequel as its ‘Bible of belief,’ as ‘the book of the future’. He once received a letter from an addict, serving time in prison, which read, Ί assure you that whether I take drugs or read The Odyssey, it’s the same trip!’ He later met the fellow while lecturing in Michigan. He presented Friar with an LSD sugar cube which he has not as yet felt the urge to use.

The Odyssey never caught on in England despite the fine reviews it received. ‘It’s too much for them,’ he suggests, ‘it doesn’t appeal to their reserved character.’

Armed with large scrapbooks, Friar relives the excitement of publication and the ensuing acceptance across America. Reviews, articles, news stories, and advertisements from the front-page book sections of The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, Saturday Review and many others. The Odyssey was also the choice of three book clubs: Book-of-the-Month Club, The Reader’s Book Club, and The Seven Arts Club.

Just as interesting — in quite a different way — as his critical success, was the story of his trip to South America where he wrote the introduction and corrected the proofs of The Odyssey during the last months of 1957 and the first half of 1958. He chose Latin America because he wanted to visit his relatives in Chile whom he had not seen since he was three years old. He speaks of being with his uncles Gabriel, Fotis, and Herakles, and with his aunts, Meropi and Pulheria, in the desolate port-town of Antofagasta; of travelling through most of Chile with another uncle, Agammemnon from Santiago; of lecturing at the University of Santiago; of joining a group of writers and professors on a cultural goodwill tour of two newly established villages in the god-forsaken territory near Tierra del Fuego; of collapsing for a month on the beaches of Rio after correcting the final page proofs of The Odyssey; of his frustration at having missed an opportunity to travel up the Amazon; of viewing Voodoo dances with a friend from the University of Bahia in Brazil. Friar tells his anecdotes amusingly.

Once The Odyssey was published in December of 1958, the quiet life of a translator gave way to the dizzying social whirl of instant success. His publisher and friend, Max Schuster, sent out an unheard of number of reviewers’ copies — five hundred — and hosted a gala reception for Friar at the Twenty One Club which was attended by influential publishers, writers and artists. The late Spiros Skouras, then director of Twentieth-Century Fox, bought the film rights to The Odyssey and invited Friar to Hollywood to write the screen treatment. Kimon got along well with Skouras. ‘He was a born peasant. I liked his wily simplicity.’ Twentieth-Century Fox Studio was filming Cleopatra that year, and Friar came to know Elizabeth Taylor and other stars during his three month stay. Burt Lancaster was interested in playing Odysseus in Kazantzakis’ epic. The script was completed, but it was shelved when Cleopatra, the most expensive film ever made up to that time, became a critical and financial disaster, thus ending swiftly and completely the Era of the Hollywood Epic.

I express my doubts about how The Odyssey could ever have been turned into a film that would do justice to Kazantzakis’ epic. In my mind, for instance, I remember Kirk Douglas as a feeble Ulysses in the 1954 film of the same name, in which he looks more like a cowboy gone to sea than like a Greek hero suffering the wrath of an angry Poseidon. Kimon laughs, admitting the impossibility of the task. He makes the point, however, that great films are seldom made from great books and that there is nothing wrong with making some money from such a project especially since many people will be encouraged to read the book after viewing the film.

Kazantzakis, in spite of Friar’s protests, had signed the royalties from the English translation over to his translator. Even though he later divided the royalties with Kazantzakis’ widow, the unexpected success of the book enabled Friar to return to Greece in 1960, to purchase his Kallidromiou apartment, and to live, modestly, while devoting his energies to translating and writing.

When he returned in 1960, he realized that he had come ‘home’ for good except for excursions abroad. Much of his time since has been devoted to work on his anthology, Modern Greek Poetry. He launched a journal in 1960, The Charioteer, published by the Parnassos Club in New York, and in Athens launched another, Greek Heritage, a deluxe publication modelled on American Heritage which stresses the continuity of Greek culture from the classical period to the present. The 1974 issue of The Charioteer is dedicated to him and his work, with essays on his translations by the co-editors, Andonis Decavalles and Bebe Spanos. In addition to lecture tours of America — in 1971 alone he lectured at seventy universities on Greek poetry and against the junta — and teaching positions as a^ visiting professor, he serves as the Greek editor for Books Abroad and The Charioteer. With the aid of a Ford Foundation Grant, he is hoping to finish his anthology of Contemporary Greek Poetry within the next two years. He speaks of the future as if it were infinite and seems to have little intention of reducing the strenuous pace he has maintained for so many years. He is translating Homer’s Odyssey into iambic hexameter to be bound together with Kazantzakis’ epic when completed, a project suggested by the late Max Schuster. Temple University Press is publishing his translations of selected poems by Odysseus Elytis this month — The Sovereign Sun. In November a collection of ten essays he has written under the title of The Stone Eyes of Medusa (in Greek) will appear, and a bilingual edition of a Iongish poem, The Nativity, (translated into Greek by Kazantzakis), with five coloured illustrations by Rouault. Another book, Aspects of Duality in Literature and Art, will contain his aesthetic philosophy.

What is this duality of which Kimon Friar so often speaks? Essentially it is a view by which a work of art is seen as the product of tensions between antitheses. This pervading sense of conflict in the creative act has allowed Friar to see not only a poem as a work of art, but also to see through it and back to its source of inspiration at the initial battle between joy and pain within the poetic psyche.

A mask may be simply the face a man puts on in his approach to his vocation. Certainly this is true of Friar who — as translator, poet, and critic — has adapted a great variety of inner gifts to suit, outwardly, each specific task that he has set before him.

But a mask may be more than this. It may have an identity of its own. So striking is the capacity of Friar to identify himself with the poetic experience of others — as apparent in the Keats of his youth as in the Kazantzakis of his middle age — that Friar may be said to have worn the mask of all the poets he has translated.

Friar is more enraged than frightened by death. He is not afraid of death, he simply loves life. He quotes a favourite line from The Odyssey: ‘Death is the salt that gives to life its tasty sting.’ ‘Death is a reality we must face,’ he states simply, ‘but I feel like the Greeks of the demotic songs who wish to wrestle with Charon, fighting as if they might win, even though they know they must lose in the end.’ He has much work to do and he is determined to complete it.

Friar is in a hurry to keep an appointment with a writer-friend. Outside we climb into his car as the sun is disappearing behind a jagged skyline. He threads his battered Fiat through evening traffic. I think of the opening lines of Kazantzakis’ epic in the Friar translation:

Ο Sun, great Oriental,

my proud mind’s golden cap, I love to wear you cocked askew,

to play and burst In song throughout our lives,

and so rejoice our hearts. Good is this earth,

it suits us!