Men have been keeping track of time for about 5000 years. The first chronometers were simple: they worked on the same principle as the medieval hour-glass, but used water instead of sand. A pot was filled with water which then ran out slowly through a small hole in the bottom. These water clocks (called ‘water thieves’ by the ancient Greeks) were used in the law courts of Athens during the days of Pericles. A speaker was allotted one or two pots of time in which to deliver his oration, and then his time quite literally ran out.

By the Roman period the fascination with gadgetry that still dogs us today had already taken hold of the human race, and more elaborate time pieces were devised. The same hour-glass principle was used to power fantastic dials and mechanical figures. The Tower of the Winds in the Roman Agora housed just such a showpiece.

‘The Tower of the Winds’ — the name alone conjures up pictures of a magical retreat in a Tolkien fantasy. But this tower is real enough. It stands just east of the ruins of the Roman market place, and is entered from a quiet little square in Plaka, overlooked by a few old houses and an artist’s atelier.

Inside, a Moslem prayer niche in the south wall recalls the days when the Tower served as a Turkish tekke. Stuart and Revett, English architects who studied and sketched the building in the eighteenth century, describe it as ‘a Place of great Devotion, in which at stated times certain Dervishes perform the circular Mohammedan Dance.’ In those days the Tower was virtually smothered by houses built right up against its walls, and the Englishmen had to remove parts of these before they could begin to draw. The Moslem mullah in charge of the sanctuary kindly allowed them to excavate inside the building, where seven feet of earth, beaten down by the whirling of the dervishes, had accumulated on top of the original floor.

Today the Tower is a conspicuous landmark, standing virtually complete while the structures around it are in ruins. The building is a simple octagon in plan, with two columned porches at the front (their columns now missing) and a round turret at the back. It was designed by Andronikos of Kyrrhos, either a Syrian or a Macedonian, who enjoyed a considerable reputation as an astronomer and geometrician. Time pieces seem to have been his specialty, and an intricate sundial signed with his name has been found on the island of Tinos. He built the Tower around 50 B.C., when this area was the business center of Athens. Immediately to the east was a deluxe, marble-paved public toilet, and beside it, the entrance to the market place. Certainly a clock would have been a convenience here, where men met daily to bargain, buy and sell.

The clock for which the Tower was famous was inside, but one could also read the time and weather from the outside of the building. High up on the walls are winged figures representing the Winds. There are eight in all, one on each wall, each carefully labeled with its classical name. The building is oriented precisely in relation to the points of the compass. The figure of the north wind, for instance, faces exactly north. Each Wind carries an identifying object suitable to his character. Gentle Zephyr, the west wind, carries flowers. Notos, the wet south wind, empties a pitcher of water. Our old friend Meltemi, under the alias of Boreas, carries a conch shell to blow up his roaring gales.

On the top of the conical roof of the Tower there once stood a bronze weather vane in the shape of a snaky-tailed Triton who pointed in the direction of the Wind that was blowing. There are also nine sundials on the walls — one below each Wind, and one on the turret. From these one could read the time of day and the season of the year.

But what of the mechanical marvel inside the tower? Ancient writers describe the building as an horologeion — a general term for any time-keeping device, were it a simple sundial or a complicated water clock. Scholars are agreed that the Tower contained an elaborate clock (and possibly a planetarium as well). These machines, like the simple clocks of Pericles, were powered by water. Although the bronze works of the clock vanished long ago, experts have been able to reconstruct them on paper from incisions on the floor and walls and from descriptions of similar devices written in the first century before Christ by the Roman architect Vitruvius.

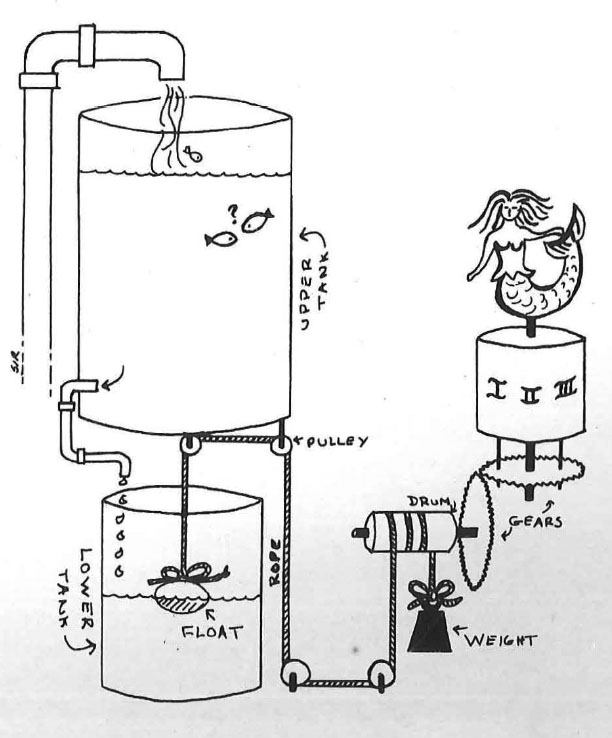

The reconstruction results in a sort of Rube Goldberg contraption that must have worked something like this: there were two tanks, one above the other, in the turret. The upper one was kept constantly full of water, piped in under high pressure from a spring at the base of the Acropolis. The water flowed out of the upper tank through a small opening or a pipe in the bottom, and into the lower tank. Thus the water level in the lower tank rose slowly and evenly; it would probably have taken a whole day to fill it completely. It would then have been emptied and the process repeated the next day.

There was a float in the lower tank which rose at a constant rate with the water level in the tank. It was attached to a rope which was, in turn, wound around a drum so that the drum turned as the water rose. The drum was attached to a gear, and the motion was communicated through a series of meshing gears to whatever sort of indicator was used to mark the hours.

It is anyone’s guess what the visitor to the Tower would actually have seen. The works of the clock would have been concealed, the noise of their motions masked by the playing of fountains. The problem of how to design a clock face was complicated by the ancient method of reckoning hours, somewhat different from our own. Instead of dividing the whole day into 24 hours, the ancients divided the time between sunrise and sunset into 12 equal parts. Thus the length of an hour varied from 47 1/2 in mid-winter to 74 minutes at the summer solstice. Only on the equinoxes would an ancient hour have been exactly 60 minutes long. Obviously a simple clock face like the ones we use today wouldn’t do; ancient engineers had to devise astronomical maps, revolving, figures and other such machines, whose movements could be adjusted to accommodate hours of different lengths. On one clock, described by Vitruvius, ‘the hours are marked on a column or pilaster; and these are indicated by a figure rising from the lowest part and using a pointer through the day.’

The Tower may well have contained other water-driven curiosities. Vitruvius tells us that in some clocks ‘figures are moved, pillars are turned, stones or eggs are let fall, trumpets sound, and other side-shows.’ In fact, the place may have been rather like a giant cuckoo clock.

All these wonders, whatever they were, have long since been melted down or beaten into swords and plowshares; today we see the watch case with its works removed. The Tower serves as a storeroom for lesser antiquities, its floor cluttered with broken statues, marble slabs and fragments of Roman inscriptions. This place, once renowned as an example of the utmost in modern technology, is now revered only for its antiquity.