Part One: The American Portrait

Translator, teacher, critic, poet, writer, lecturer, director, editor, reviewer: these are the vocations to which he has applied his inexhaustible energies. Indeed, his curriculum vitae, listing all his publications to date, reads like an encyclopaedia entry for a middle-sized country.

Yet Friar has not confined himself to the monastic literary life of, say, a Proust. He has embraced life and art with the Dionysian gusto of Kazantzakis’s own Zorba.

I arrived at his rooftop apartment on Odhos Kalidhromiou with a neatly typed list of questions and a tape recorder under my arm for the first of several visits during which I listened to Friar discuss his life. The list was to be completely unnecessary while the tape recorder proved indispensable: Friar took the microphone with confidence and plunged into his life story.

Before we began, however, we chatted briefly as he boiled water for coffee, and the interval gave me an opportunity to look around his living room.

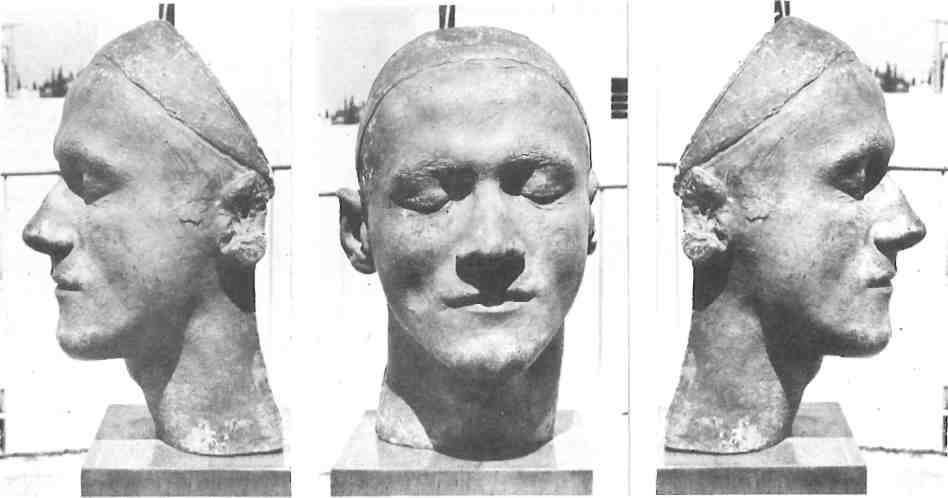

The walls of the room are lined with book shelves, photographs, paintings and memorabilia. Considering the amount of things he has collected in such a limited space, the room is cozy rather than cluttered. Most striking is a large Medusa head hanging on the wall above the couch. This work was composed by Ghika from odds and ends found around Friar’s cottage in Poros. There is an oil portait of Friar painted by Tsarouhis in 1946. Prominent on the parlor table is a life mask of the young poet. A human skull perches on a bookshelf.

Friar is small in stature but has the nimble movements of a jockey or a dancer. He speaks dramatically, often exploding into laughter. His eyes sparkle even through thick glasses. The balding of his head has added with age a sculptured quality to that very Greek figure in the photographs he was later to show me of himself, as a young man, with a bushy crop of curly, jet-black hair.

Born on the island of Kalolimno in the Sea of Marmara, he is proud of being a ‘true Greek’. At the age of three, Friar was taken to the United States where he and his brothers, John and Dino, grew up and were educated, and became American citizens.

Kalolimno is now completely inhabited by Turks but in 1911, when Friar was born, the population was wholly Greek, with the exception of the tax-collector. His family was well-off and respected. On his paternal side he is descended from what were great landowners — but, he adds, ignorant peasants — of the island.

The members on his mother’s side of the family were well educated. His maternal grandfather, Hadjiconstantinos, owned ships which sailed from the Black Sea down to Alexandria. Having made the had;, or pilgrimmage, to Jerusalem and been baptised in the river Jordan, he had earned the privilege to prefix ‘hadji’ to his Christian name.

Kimon is an unusual name but one which pleases him greatly. It was the custom for many Greek families living in Turkey and the nearby islands to give their children classical names — his uncles were Agamemnon and Menelaus, his aunts Merope and Pulheria.

It was also customary in those days and, to some extent, today, for the godparent to choose the godchild’s name and not reveal it until it was announced during the baptism. Kimon’s father discovered somehow that his son’s godmother planned to call him ‘Jordan’, after the river, and he was furious. ‘So the moment came when the priest asked for my name in church’, explains Friar. ‘As my godmother opened her mouth to say Jordan, my father instead yelled out, Kimon! So Kimon I became’.

How a true Greek came to be called ‘Friar’ is another story. His family’s name was originally Mitsakas. His paternal grandfather, however, spent some time on Mount Athos before deciding that the holy life was not for him. He returned to Kalolimno where he was henceforth teasingly called ‘kaloyeros’ or ‘monk’. Kimon’s father thus inherited the ‘paratsoukli’ or nickname and became ‘kaloyeropoulos’ — son of the monk.

The problem of nomenclature was not to end there, however. When his father went to America, Friar explains, he grew tired of people asking him how he spelled his name. In search of a solution to his dilemma, he looked into the dictionary and found that the first definition of kaloyeros was ‘monk’. Monk… monkey? This wouldn’t do! The second definition was ‘friar’. ‘So my father chose that. Friar, the peripatetic… and fortunately for a literary man, it goes with Kimon. Kimon Friar goes well’.

The eruption of the Balkan War in 1912 created an unbearable situation for the Greeks on Kalolimno. Confronted with the dilemma of remaining behind and fighting in the Turkish army against their own people, or leaving their homes, most Greeks chose the latter course and escaped. The relatives on his mother’s side fled by ship to Chile. His father travelled by boat to New York whence he moved on to Chicago where he had some connections. Kimon and his mother remained behind and did not escape until the eve of the first World War. In those days nuns sometimes used to come to Kalolimno from Constantinople to buy fish, ‘And so’, says Friar, ‘my mother dressed as a nun… and I was hidden among the fish’. This was the first of many adventures that led at last to Chicago where father, mother and sons were finally reunited.

Today his brothers, John and Dino, own a large restaurant, called Friar’s, and a bowling alley in Lombard just outside of Chicago.

‘But when we first came to Chicago, we lived in a tenement house that took up the whole block’, continued Friar, Ί remember that Saturdays it was my duty to douse all the bed springs with kerosene to kill the bed bugs.’ The childhood he describes was not unlike that narrated by James T. Farrell, in Studs Lonigan, marked as it was by poverty, petty theft, and hardship. As a young boy, he now jokingly says, he was a ‘gangster’ and, pointing to his front teeth, explains that he lost the originals in gang wars. His father had begun his American experience as a truck driver and eventually became the manager of an ice cream factory. In their apartment on Huron Street, the one thing they always had was plenty of ice cream.

Kimon Friar never felt American. None of his friends in the neighborhood, in fact, were ‘American’. They were Greek, Italian, Jewish, Polish and German. At grade school almost no one spoke English, he recalls, and he grew to hate Greek because ‘father taught me Greek the hard way — by beating it into me*. As a result, he was unable to speak any language well and this handicap was to remain a deep frustration for many years.

At the age of twelve he rose out of poverty as suddenly as he had fallen into it. His father, a stubborn, hard worker, had saved enough money to invest in his own ice cream parlour. As a result, his fortunes improved and he was able to buy a house in Forest Hills, then a ‘posh’ suburb of Chicago. Ί had never seen a tree, you see, then suddenly… a park, a lawn, a lake, a conservatory… it was absolutely heavenly’, he recalls even today with animation and delight.

His time was not his own, however, and it was at this stage in his life that Friar acquired an expertise in an art that is not mentioned in his curriculum vitae. For the rest of grade school and throughout high school the young Friar worked in his father’s ice cream parlour from three in the afternoon to three in the morning. ‘I’m an expert soda jerk’, he boasts with evident pride much as if he were saying, ‘I’m an expert translator’. Impressed and amused by this revelation of an unsuspected talent, I inquired whether or not he had had to eat his mistakes. ‘Eat my mistakes? I never made any. I was very good. An expert soda jerk, really!!’

It was at Previso Township High School in Maywood, Illinois, that Friar stumbled upon a discovery that was to change his life. In high school he had begun concentrating on art because of his still inadequate command of the English language.

‘Then one day I read a poem called “Ode on a Grecian Urn”. Suddenly I realized how beautiful English is.’ He ran to his teacher and asked, ‘Who is this guy, Keats?’

Young Kimon thereafter checked out of the library every book he could find on the subject of Keats, and read them all avidly. Truly ‘a new planet had swum into his ken’ and thus began the long, romantic, and curious relationship between Kimon Friar and John Keats. Ί fell in love with Keats’s poetry and with Keats as a person’, he reminisces. Wishing to understand his new friend better, he arranged all of Keats’s poetry and letters in chronological order — a task which has since been completed and published by others but one which had not been done at that time.

He became completely involved. ‘When I was… let us say sixteen years old, three months and two days… I read that poem or that letter which Keats had written exactly at the same age, to the day!’ If it were a poem, he would read it with great care and write a letter to the poet. On one occasion he wrote, ‘Dear Keats: I recently received “Ode to a Nightingale”. Not bad! But I don’t agree with you… Here I think there should be a semicolon and not a colon, here I would change this word to that word… the metre halts.’

He wrote these letters with engrossed dedication and the labour that went into them marked the beginning of Friar’s understanding of poetry. ‘If I know anything today about the technique of poetry, and that’s one of the things I know well, it’s because of this dedication in analyzing the poetry of John Keats… and today when I recite John Keats… I know most of it by heart… I can’t tell you if it’s Keats I’m reciting or Friar’s revisions of Keats!’ So deep was the young student’s indentification with Keats that it even seemed to include a physical likeness. The celebrated life-mask of Keats was executed when the poet was twenty-two. At the same age Kimon executed his own. It now sits on a table in his living-room.

Looking at his life-mask, Friar observes, Ί think it is the sensitive head of the poet I then was. I had sculpted myself from within and I made myself Keats. Many people have come into this apartment and mistaken it for the life-mask of Keats.’

The identification did not stop there. Kimon assumed as well the role of each person with whom Keats had corresponded — whether they were friends, relatives or sweetheart. In his infatuation he wrote to Keats such letters as he imagined they would have written him. Friar, however, allowed himself a few anachronisms. Deliberately confusing the centuries, he would keep the other poet abreast of the current literary scene, and the latest theatrical or movie productions in Chicago.

The friendship, however, eventually had to come to an end. ‘When I approached twenty-six and I knew he was dying… I was then at the University of Michigan… I rented a house on Lake Superior… there I waited as he sailed out on the Maria Crowther to Rome, consumptive, spitting blood, Severn his only companion — there I watched John Keats die.’

Friar was, at the time, busy reading the works of Yeats, Pound, Joyce and Eliot. When Keats’s death came he took it, he explains, ‘quite calmly because I had been expecting it so long.’ He locked up all of his letters and notebooks and has not looked at them since even though Max Schuster, the publisher, once suggested that he bring out a book entitled Correspondence with John Keats.

Grafuating as an art student from high school, he won a handful of awards including a scholarship for one summer at the Art Institute of Chicago. But the continuation of his education was problematic. The year was 1929, and the Depression was fast becoming a reality. His father’s ice cream parlour failed and Kimon, about to embark on his university training, was without financial support. Borrowing a hundred dollars from the local Kiwanis Club, he entered at the University of Wisconsin an unusual program, called The Experimental College. The two-year program was directed by Dr. Alexander Meiklejohn who, not long before, had been fired as president of Amherst College for his ‘radical’ educational ideas. At Wisconsin Dr. Meiklejohn had set out to correct what he saw as the ills of American higher education. Traditional classroom and marking procedures did not exist. Students lived together in the same dormitory, mingled freely in each other’s rooms, exchanging ideas, reading recommended books and develop-ing individual projects.

In the first year all students studied an ancient civilization. Ί was in luck!’ laughs Kimon with delight, ‘My first year he chose Greece!’

Friar selected Ancient Greek as an optional course and soon found himself translating The Bacchae of Euripides. He was back with poetry which, through Keats, had been his second love. His project then became the production of the play. He threw himself into it with all the fervour of his youth. He found an ‘ancient’ open air theatre — a livestock pavilion at the Agricultural College which became a natural amphitheatre when blocked off at one end. Over a period of eight months he orchestrated every aspect of the production and now recounts the details of this enterprise with zest. Ί built a huge set, seventy-five feet high, sixty feet long, a great castle wall and all that business. I got a girl in the department of music to write the music for The Bacchae for her Master’s thesis. I went to Miss Dobler, a famous teacher of modern dance, and asked her to arrange the choral movements. Miss Dobler choreographed the first chorus and then showed it to the young student and asked what he thought of it. ‘Dreadful, awful,’ was the reply. ‘You’re emphasizing the movement. I want the words emphasized. The movement should support the words; the words should not be subordinate to the movement.’ And so she asked if he would like to do it. ‘Well, when you’re young — I was nineteen — you’ll dare anything!’ Friar now laughs, ‘So I did.’ Fascinated by the Dionysian, as opposed to the Apollonian, aspects of Greek culture, he finally performed a ‘revolutionary’ and definitely non-classical version of The Bacchae which he characterizes as the most Dionysian of all Greek drama. Ί dressed the chorus in yellow, red, and orange… the set was a red-violet. Dionysos was in gold and he came down through the audience to give his opening speech!’ The play was well-received, but what meant most to the young poet-director was a comment from Dr. Meiklejohn. ‘After the production, he, whom I adored and admired… he was the father I would have loved to have had… came to me, put his arms around me and said, “Kimon, one day you will do great things.” His faith in me has been my great support throughout the years in moments of despair.’

On the strength of his script and production book for The Bacchae, Kimon Friar was accepted at the Yale Graduate School of the Drama in what was his junior year. Seriously interested in playwriting and directing, he had the opportunity to study under such renowned teachers as George Pierce Baker, Professor of Playwriting, and Alexander Dean who wrote and taught directing. He left Yale after one semester, partly because he was ‘deadly poor’ and also because he had come to realize that he could not dedicate himself to theatre. ‘The theatre eats you up,’ he now explains. ‘It takes up every free moment of your life.’ I asked him what he learned at Yale and he replied, ‘How to speak English without a Chicagoese guttersnipe accent!’

His finances were shaky but he was fortunate to have friends and admirers who acted as benevolent patrons and sponsors. One such charitable soul was the Midwestern writer, Zona Gale, who later married a Mr. Breeze, and thus, ‘was demoted’ to Zona Gale Breeze. Because she appreciated his poetry and believed he showed promise, the writer sent the young poet twenty-five dollars a month for two years. It soon became obvious that he needed more than that to make ends meet (he was working as a waiter among other things) and so she introduced him to the Midwestern paper baron and millionaire, George Mead. He asked him how much he needed a month and Kimon calculated that his expenses would amount to sixty-nine dollars and fifty cents per month. Mead offered to provide it.

The young revolutionary had second thoughts on the matter, however, and fired off a special delivery letter to Mead. ‘I’m a socialist’, he wrote, ‘You’re a Republican, a trustee of the university, and I might have occasion to attack you in the newspapers.’ To this the older man replied, Ά young man who in his youth is not a socialist, isn’t worth a damn!’ So it was that for five years George Mead helped Friar and was even willing to reward his impudence by offering him a position in the management of one of his mills. Were he to accept, he assured Friar, he would become a millionaire in short order because he believed that the young man possessed ‘vision.’ Kimon declined the offer gracefully.

After leaving Yale, the retired dramatist completed his last two years at the University of Wisconsin. Being a Junior, however, he could no longer enjoy the freedom of The Experimental College. He claims, in fact, that until he learned to give the teachers what they wanted, he nearly failed. He was too busy educating himself, on his own. He graduated in 1934 in the depths of the Depression, having won a number of scholarships which enabled him to continue his studies.

Degree in hand, a head full of disappointed ambitions, and with no money of his own in his pocket, the young man had no place to go until Phil Garman, a Wisconsin student friend, came to his rescue. Garman wrote, telegraphed, and finally took Friar to Detroit where he was working as an assistant to the first organizer of the United Auto Workers’ Union. Phil put his friend up for a few months while a grateful Kimon kept an account of how much he owed him. Later he repaid the entire amount.

It was during his stay in Detroit that his friendship began with John Malcolm Brinnan with whom he later edited the prestigious anthology, Modern Poetry: American and British. He remembers that at that time Brinnan was publishing a highly ornate, artificial, ‘Shelleyesque’ poetry magazine called Prelude. Friar together with some other friends had meanwhile begun to bring out a socially committed counter-journal called New Writing.

Brinnan one day appeared at the office of New Writing and proposed that they join forces because he felt that Prelude was headed in the wrong direction. The alliance was sealed when Brinnan presented him with a two-volume Florentine edition of Keats’s poetry.

Thus, at the age of twenty-three, Friar won over his first acolyte from the world of poetry and assumed the role of teacher. He worked hard with his pupil. Τ taught him all I knew.’ When Brinnan published his first collection, 77ie Garden Is Political, a title typical of the thirties, it was dedicated to Kimon. Many of these poems were written to him, for him, and about their friendship. Going over to his shelves, Friar took down the book and read passages from these poems out loud.

The light outside the window had begun to pale. He had been up, as usual, since five in the morning. We stopped briefly to switch tape and ‘breathe’, but unlike the fading light, Friar still radiated the same vitality with which he had begun.

‘Let’s see… Where were we? In Detroit… Oh, yes, now she was very cunning…’

Unable to find more than a minor job at the Detroit Library, he went on relief in order to get a job on the Michigan State Guide Book, a Public Works Administration project designed by the Roosevelt government to create work for the unemployed. He became a ‘professional editor’.

The director of the Guide Book project was a conservative Republican, he a socialist. ‘She had heard about New Writing and the Communists that worked on it and decided that I was a Communist. She had to get rid of me and found a beautiful and adroit way.’ She called him in one day and said, ‘Mr. Friar, you write beautifully. Such style! Such elegance! The trouble is, it’s too good for a thing like the Michigan State Guide Book.’ Kimon laughed. ‘Really, she was very cunning! She said that she was sorry but she’d have to let me go.’ And so ‘the Communist’ was fired. The next day he learned that the central office in Washington had sent out copies of one of his articles, ‘The Flora and Fauna of Michigan,’ to the projects in all forty-eight states commenting that this was the style that should be followed! ‘So I wrote to Washington and insisted on an investigation. A guy came down to look into it, and she was fired!’

Friar was hired back but resigned soon after to join the Detroit Federal Theater. About fifty performances of his B.A. thesis, Ά Modern Version of Christopher Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus’ were presented throughout Michigan. It was during that year, 1936-37, that he became deeply involved with the Civil War in Spain. ‘Many of my friends fought with the Lincoln Brigade and were killed… Ever since, I have kept my interest in politics.’

The following year Kimon worked on his M.A. at the University of Michigan, concentrating on Yeats and writing a thesis on Yeats’s book, A Vision. ‘My other great love, besides Keats, was Yeats,’ he explains. Ί identified myself as thoroughly with Yeats as I had with Keats.’ His thesis, a slightly altered version of which will soon be published in Greek, won him a university essay award.

John Brinnan was attending the University of Michigan at that time and opened a bookstore on the campus. He had wanted to call it ‘The Poet’s Head’ after the life-mask which Kimon had made of himself years before. Friar persuaded him, however, to change the name.

Another fellow student at Michigan was Arthur Miller. They became friends but he regrets that he once encouraged Miller to write in verse! According to Kimon, ‘Arthur has a very poetic strain in him… not poetry per se… but in what I call poetic realism. In all of his plays you will find ordinary remarks that have a poetic glow.’

Upon receiving his M.A. in 1940, he attended the University of Iowa in order to work on his Ph. D. in English. He had previously ‘taught’ poetry to friends like Brinnan and had delivered lectures at Brinnan’s Michigan bookstore, but it was at Iowa, as a graduate assistant, that he taught for the first time officially.

Finances, however, were again a problem. When he was offered an instructorship at Adelphi College for women in Garden City, New York, he abandoned his ambition to earn a Ph.D. and went to Adelphi where he was to teach for five years. ‘There’s nothing I didn’t teach!’ he exclaims about those years.

While at Adelphi, Friar managed to stir up at least one controversy by writing a choral poem for a Christmas Nativity dance program, which was later translated into Greek by Kazantzakis. Hesitant at first to write on such a traditional theme, he took up the challenge when the dance instructor promised to allow him total freedom. In his updated revision of the familiar story, the Annunciation was the creation of a new economic order in America. Christ was born in the New York slums; his mother, Mary, was a typist; and the flight into Egypt was the outcome of the police pounding on the tenement door. Written during the Second World War, the poem also referred to current political and social events, and the bombardment of civilian populations. The final touch, according to Kimon, was that ‘the Three Magi were the trustees of the university!’ When he read the poem to his students, many were so offended that they complained to their parents who harassed the university president. But the president understood that his young instructor wished to update the story of Christ as the Prince of Peace. He supported the irreverent instructor’s biblical revisionism after they both agreed to brand the appearance of the trustees as apocryphal. The lines have an unsentimental boldness about them that still rings true after thirty years. ‘It’s always been my desire,’ he says, ‘that Theodorakis should write the music for the Greek version as it was translated by Kazantzakis.’

It was also at Adelphi College that Friar began teaching at the downtown branch, called The Mills School, which specialized in teacher education. Martha Graham was teaching dance in the same building on the floor below and this led to the beginning of another lasting friendship. It was at The Mills School that Friar revived his staged version of Dr. Faustus, casting himself as Faustus and his students (all girls) as the Seven Deadly Sins.

After the performance, he relates, s gentleman came up and offered him the directorship of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association poetry program. On what grounds? I wasn’t Jewish. Well, just because he had seen me act. I liked that! I accepted. I could see right off that he was my kind of man.’

At this point Friar turned off the tape recorder and disappeared into another room, returning with five or six mammoth scrapbooks. One of these is dedicated entirely to programs and articles concerning the Poetry Center.

‘This was quite a period in my life,’ he says as he thumbs through the scrapbook which represents over four years of his work. He is clearly delighted with its contents, but does not speak with any trace of nostalgia about the irretrievable past, only with a childlike enthusiasm as he re-lives each experience.

The Poetry Center at the Ύ had been a limited project until he took over. He swiftly turned it into the place in America where one could hear important poets, writers, dramatists, and artists read and discuss their work. As he turns the pages, the name of almost every significant poet of that period appears. Among them are Robert Penn Warren, W.H. Auden, Karl Shapiro, Robert Lowell, Herbert Read, Archibald MacLeish, William Carlos Williams, Dorothy Parker, James Agee, Leadbelly, Randall Jarrell, Kenneth Patchen and Anais Nin. He presented the surrealist poetry of Charles Henri Ford sung to the music of Paul Bowles, plays by e.e. cummings and Gertrude Stein, a Noh drama by Yeats acted by a Japanese troupe, and gave the first showing of experimental films by Maya Daren, who has since been acknowledged the ‘mother’ of avant-garde cinema in the United States. He presented Mary Averett Seeley who danced to poems by Gertrude Stein, Edith Sitwell, Wallace Stevens, T.S. Eliot and others.

His contact with such distinguished individuals was stimulating but there were moments when even he could suffer from an excess of poetry. On one such occasion Allen Tate was reading his verse. Friar, sitting in the audience, had become totally absorbed in his own thoughts. As the applause at the end, however, was prolonged, Friar struggled to his feet and addressed the poet, ‘Well, Mr. Tate, obviously the audience would like an encore. Why don’t you read your great poem ‘Ode to the Confederate Dead”?…’ An awesome hush fell over the audience. Tate looked at him coldly and said, ‘Mr. Friar, I have just this moment finished reading the “Ode to the Confederate Dead”…’

The readings of celebrated poets were not, however, the only activity he organized at the Ύ. One night a week he would arrange a reading that combined a well-known poet with an unknown, but promising one.

On other evenings he lectured on one of a variety of subjects, such as ‘Aspects of Duality in Literature and Art’, The Banquet of Love’, The Psychology of Sex Relations’, The Swan in Literature’ and The Human Body: Its Landscape and Inscape’. He also lectured frequently on drama and poetry, both contemporary and modern, on Eliot, Pound, Joyce, Yeats, Hopkins, Crane and, of course, on John Keats.

He also conducted what he believes were among the first poetry-writing seminars in the United States, for which he selected ten students from among as many as fifty applicants, whose poetry he felt showed potential. Later, he published an anthology of his students’ work, The Poetry Center Presents. Many of these poets have since made their mark in American literature.

Though it is Friar’s belief that poets are born, not made, he also believes that the craft or technique of poetry can be taught to those of talent. He used to tell his students, for instance, that if they wished to write in free verse they first had to learn and master that from which they wished to be freed: namely, the various and traditional forms of metre and verse, that have appeared in English poetry in the past.

After four years, he turned the project over to his old friend, John Malcolm Brinnan, with whom he then began to work on an anthology, Modern Poetry: American and British. He and Brinnan read over two thousand books on poetry before making their selections. Friar alone was responsible for over a hundred and fifty pages of notes on the poems and poets and for the introductory essay ‘Myth and Metaphysics’ which he considers to be among his best work. The book has been widely used in college poetry courses and has received praise from such critics as Allen Tate (who had apparently forgiven him for the episode at the Ύ) and who has called it ‘in many respects the best anthology of modern verse in English.’

While Friar was meeting with success as a teacher, lecturer and editor, he was troubled by a sudden inability to continue his creative writing. Sitting down to write a poem or an essay his heart would begin to pound, his body to tremble. In New York, Friar had come to know Dr. Theodore Reich, the psychoanalyst and former pupil of Freud. Dr. Reich had been in the United States for only a few years when Kimon was asked by a friend to help the psychoanalyst improve his written English. Friar accepted the task and soon became a good friend and interested follower. He discussed the problem he was facing with Dr. Reich who suggested psychoanalysis. Dr. Reich could easily have guided him through analysis free of charge, but he said that only if he paid him something would the ‘patient’ feel truly committed to his own recovery. The figure arrived at was ten dollars — the normal rate at that time was twenty-five — a large sum for the struggling teacher on a college instructor’s salary. He went every day, seven days a week, for over a year.

With Dr. Reich’s help, he came to realize that the source of the block to his creativity lay in his relationship with his father. He had been fighting his father since childhood and, being ‘stronger,’ had succeeded in establishing his own identity. If he had not, Friar says, his father may well have symbolically killed him. Therefore I became what he didn’t want me to become… a writer and a professor.’ He laughed and continued. ‘Ah, but I paid dearly for it! Only under Dr. Reich’s direction did I come to realize that from the time I had first begun to succeed as a writer, and to publish, I had substituted society in the place of my father. Unconsciously, I had become afraid of critics whom I had cast into a father role.’ Once he came to understand this he began to write again, and has never stopped since.

Kimon spent the summer of 1945 with the Reich family in the countryside of upper New York state. His therapy completed, Friar was told by Dr. Reich, The end of your analysis is: go to Greece!’ This he did in the following year.

The End of Part One